If ever there was a time for activism, surely this is it?

Climate change is the defining challenge of our generation. Naturally, people wish to act to protect our planet. The divestment movement has tapped into this desire, as evidenced by the steady flow of institutions deciding to sell their shareholdings in fossil fuel companies. There is little doubt that this has contributed to the political imperative to act.

The trouble is that divestment alone cannot be relied upon to deliver decarbonisation. For decarbonisation to be achieved, all companies will need to adapt their strategies and operations to a zero net-emissions pathway. Concerned shareholders can, and should, be supporting and pressing corporate leaders to act in this critical transition; and sanctioning those that fall short. Divestment removes investors’ ability to drive change from within1.

The shareholder imperative to act is based on a simple logic: shareholders gain where their businesses are run in their long-term interests. It follows that any business whose success is predicated on the world exceeding the 2°C cap in global warming agreed in Paris, and thereby placing planet stability at risk, should face tough questions. Likewise, a strategy that presumes this outcome – and approves capital deployment that contributes to excessive greenhouse gas emissions – is likely to be materially exposed to more rapid decarbonisation. Either way, shareholders lose.

Unfortunately, shareholder complacency is too often the norm. Take the global financial crisis. Whilst there were many factors that lie behind excessive risk taking in banks, there is little doubt that the failure of shareholders to hold bank executives to account removed a vital check on dangerous behaviour.

Inaction is, in short, inimical to savers’ and society’s long-term interests.

Urgent pleas must be heard

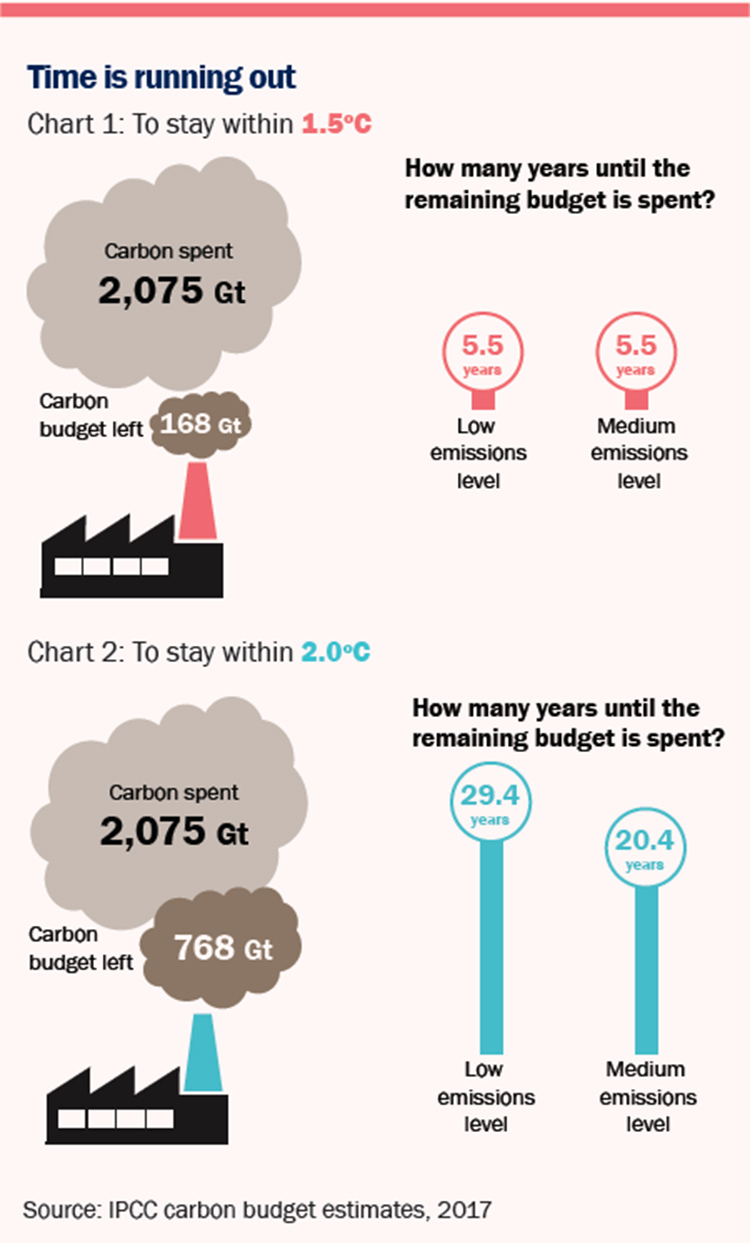

The Met Office’s recent estimates for the time we have left to act are sobering (see charts 1 and 2). If we wish to meet a target of keeping warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels then we have roughly five years left continuing to burn greenhouse gases at today’s pace.

Under the more lenient – and arguably more dangerous – pathway of capping warming at 2°C, we will need to achieve net zero emissions (so any positive carbon emissions will need to be fully offset) within 20 to 30 years.

Given the time it will take to phase out our reliance on fossil fuels, it is understandable that the scientific community’s pleas for action are becoming more urgent.

Shareholders have strong levers to pull

Investors have voting rights. Generally speaking, shareholders have the right to appoint directors, the auditor, as well as a say on funding and strategic matters such as raising capital or major acquisitions. In some cases, like the UK, shareholders have a vote to approve the Annual Report and Accounts and are given a say over remuneration for senior executives. In many instances, shareholder votes are binding. A majority vote against a director in the UK or the auditor means the individual/firm must stand down.

So, shareholders have a say, and can influence a company’s strategic direction or leadership. The trouble is that too few have historically utilised their vote to drive change, and this can disempower the rest. While heightened public and media scrutiny of voting is leading to more ‘against’ votes, for instance on executive remuneration, it is rare that shareholders drive the agenda.

In the FTSE 100 for instance, in the last proxy season no directors received less than 50% support. Even in cases where the company has been involved in poor behaviour or misconduct which has destroyed shareholder value, shareholders appear inexplicably reluctant to act.

Take Sports Direct, the sports clothing retailer. Over the past two years we have learned of poor labour treatment (in certain cases paying below the minimum wage and punitive disciplinary procedures), related party transactions, high levels of remuneration and weak governance controls. Nevertheless, the CEO, Chairman and Senior Independent Director have all continued to receive majority shareholder support. Since January 2015 and the end of 2017, the share price fell almost 50%.

Climate change offers a catalyst to spur a broader shareholder ‘awakening’, and there are early signs that this is happening.

Where material climate risk should inform votes on directors, the auditor and strategic changes

In the last couple of years, shareholders (including Sarasin & Partners) have pressed companies to take account of climate risks through ad hoc shareholder resolutions. These have received overwhelming shareholder support. The trouble is that these have framed climate risk as separate from core matters of business.

Where it is material climate risk needs to be considered as part of the routine votes at Annual General Meetings. For example, directors need to be held to account for articulating how their strategy is in line with planet stability (and thus the Paris Climate Accord), and how this will deliver attractive long-term earnings for shareholders. Where the threat from decarbonisation is potentially existential, the need for determined leadership will be that much greater.

The auditor also plays a critical – and often underappreciated – role in responding to climate risks, and should be held to account for this function. As the ‘watch-keeper’ for shareholders, the auditor is there to ensure managements’ financial statements provide a ‘true and fair view’ of the company’s underlying economic position, and the narrative disclosures including risks are complete and balanced.

Critically, the auditor reassures shareholders that their capital is protected by taking a prudent view of likely losses and liabilities embedded in the business, and preventing management from recognising profits too early. Were decarbonisation to curtail expectations of future cash flows of an oil and gas company, for instance, then the auditor should be expected to ‘kick the tyres’ for any potential write-downs in the balance sheet. If management is using unrealistic assumptions, the auditor must challenge this. If management does not comply, the auditor should decline to sign the misleading accounts. If the auditor fails in this duty, shareholders should vote to replace them.

Votes on annual reports, remuneration, mergers and acquisitions, and capital raising are also all pertinent for reflecting disquiet with how effectively a company is managing material climate risks.

Dialogue should come first, but public outreach can raise the level of debate

Voting against the board on any resolution, of course, represents the ultimate sanction available to shareholders, and should be deployed with care.

oreover, it may not be necessary. Dialogue with directors on the company’s strategic direction and leadership may offer a smoother and more effective route to change.

The difficulty is that dialogue on disruptive change can itself be bumpy. Shareholders may not speak with one voice – many investors may be opposed to action that aligns the strategy with the Paris Accord if this involves short-term pain. Also, directors frequently have different perspectives on the need for change, further complicating engagements. Divergence in views is likely to be particularly acute in companies that face the greatest threat from decarbonisation.

Navigating the politics of such engagements takes time and skill. Above all, shareholders will need to be flexible and innovative in the tactics they use.

Where dialogue becomes bogged down and silos form between different directors and shareholders, investors may consider public commentary to focus minds on the core arguments. Public scrutiny tends to expose weak arguments quickly. Shareholders arguing for ‘business as usual’ in companies whose activities put the planet at risk are as vulnerable to public criticism as companies that turn a blind eye to the societal consequences of their activities.

Shareholder activism will not guarantee success, but it is worth trying

None of the above is intended to suggest a shareholder activist approach is either easy, or guaranteed to succeed. Despite individual shareholders’ best efforts, dialogue can stall and broader shareholder momentum can wane. Entrenched management teams have an interest and resources to resist change. Public discourse, likewise, can go in unintended directions.

Notwithstanding these risks, with so much at stake, if ever there was a time for shareholder activism, surely this is it?

1There is, of course, no sense in investing in a company that will destroy capital, and any active asset manager (including Sarasin & Partners) will be focused on avoiding this. But there are many fossil fuel dependent companies that could shift course and build resilient and profitable Paris-aligned strategies.