The semiconductor sector is a uniquely global industry with supply chains scattered all over the world.

These devices that lay the foundation of modern day electronics, such as radio, computers and mobiles phones, used to be manufactured by the first semiconductor companies in America. It wasn’t until the 1960s that semiconductor companies started crossing national borders.

Fairchild Semiconductor International set up manufacturing facilities in Hong Kong in 1961, taking advantage of the lower cost engineering and technical knowledge, proximity to end-markets and low tax-rates. In the decades that followed, the arrival of modern electronics and mass computing opened up vast new markets for semiconductors across the world. US based semiconductor companies began setting up regional retail and distribution (R&D), manufacturing and testing hubs all over the world.

From fully integrated to specialised

As these new markets boomed, companies with narrower product sets began to reap the rewards of the global scale. Lower production costs supported lower unit costs, in turn creating more end markets. Over time, as capital requirements increased, an esoteric cyclicality emerged. The amplitude of which, super charged by the pace of innovation, conspired to create occasionally vast supply/demand imbalances that saw astonishing volatility in semiconductor prices. This made the production phase, with its high fixed costs and uncertain product design cycles, highly risky because it could be difficult to determine whether the demand outlook for one product would be enough to fully utilise a factory (known as a “Fabrication Plant”). This, in combination with a relentless need to increase efficiency, led to a trend of vertical dis-integration or specialisation. New companies emerged focusing on one part of the value chain, which led to a physical separation of the industry’s functions. Design companies like Broadcom, specialist tool companies like ASML, foundries like TSMC and packaging companies like AMKOR entered the industry.

China China China

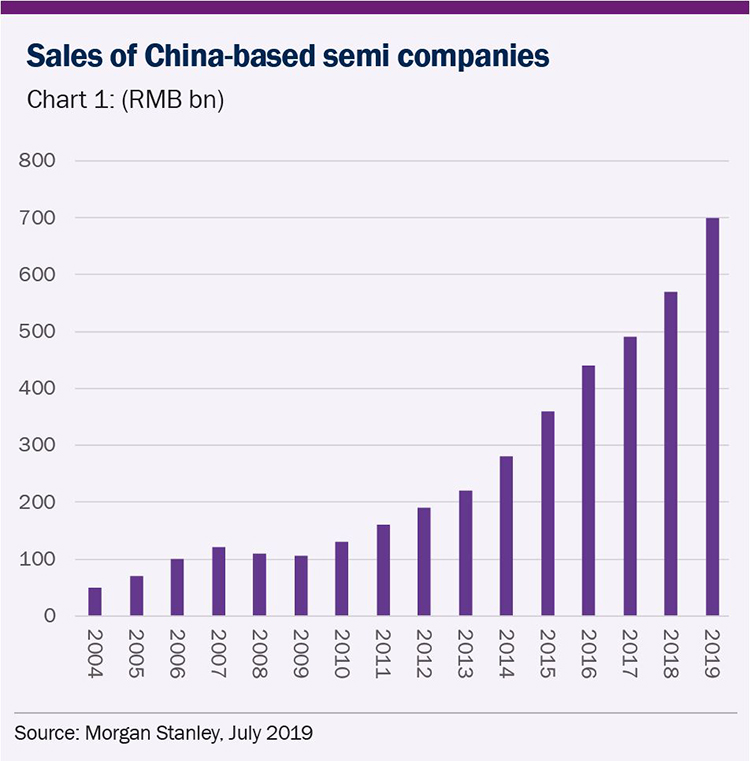

So what does this mini-history have to do with China? Quite a lot. China’s rapid economic growth has seen its demand for semiconductors skyrocket over the last 20 years. They are at once a major consumer and producer of microchips.

These technologies are considered so important for the country’s future that, in the China 2025 Industrial Policy Initiative, global leadership in the semiconductor industry ranked alongside green energy leadership, robotics and IT. In practice, this means reducing reliance on foreign suppliers, a reversal of trend over the last three decades.

How does China achieve self-sufficiency?

By investing heavily in the semiconductor industry. Until now this has involved domestic investment programmes (not to mention a little corporate espionage. See Micron’s battles with Fujian Jinhua) into the Chinese foundries, notably SMIC, in a bid to “catch-up” with the US-Taiwanese duumvirate in logic and memory manufacturing. Its slow work given the gigantic and ever increasing lead held by the logic foundries (TSMC, Intel, Samsung) which relegates China to manufacturing dependence on Taiwan for now. Looking ahead the focus will increasingly be on integrated circuit design, the R&D phase where the creative magic takes place and a position that is currently dominated by the US.

Cue trade war

China’s semiconductor aspirations have the potential to undermine the US design industry. But to do so requires not only overcoming the US incumbent’s formidable R&D entry-barriers, but building an entire value chain within one-country. A strategy which flies in the face of the last 30 years of industry disaggregation. It is an issue we are following closely; time will tell if they are successful. Despite the challenges, there are many powerful secular tailwinds in AI, machine learning, high performance computing and 5G that will lift support the sector over the long term with companies like TSMC, Broadcom and Texas Instruments are uniquely positioned to benefit from the growth.