Governments are issuing high levels of bonds, just as central banks are keen to offload their loss-making bond holdings. Will the bond vigilantes ride back into town?

I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president…But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.

James Carville, Bill Clinton’s campaign strategist, 1994

There was a time when bond markets wielded enormous power as guardians of the public purse. So-called bond vigilantes kept profligate politicians in check by pushing up interest rates. By the end of the 1990s even the US government started to run budget surpluses.

This changed at the turn of the millennium. First, the internet and globalisation dampened inflation before disconnecting it from the economic cycle. When the technology bubble burst in 2000, fears of a Japan-style deflationary trap gripped policymakers, who slashed interest rates.

The lessons from Japan’s decades of low growth and disinflation appeared to be clear: policy had been too slow and too timid. So when a US real estate crash unleashed the global financial crisis of 2007-08, central banks were determined not to repeat Japan’s mistakes. In coordinated moves, they slashed interest rates to zero and used aggressive bond buying programmes to bring about a faster recovery in demand

The global hunt for yield

In the wake of the global financial crisis, substantial and synchronised central bank bond purchases dramatically reduced the supply of safe assets in the global economy. At the same time, western manufacturers’ efforts to slash costs by moving production overseas gathered pace.

The result was a glut in global savings caused by current account surpluses across Asia and a drop-off in investment demand in developed economies. With excess savings chasing increasingly scarce safe assets, a global hunt for yield sent interest rates ever lower.

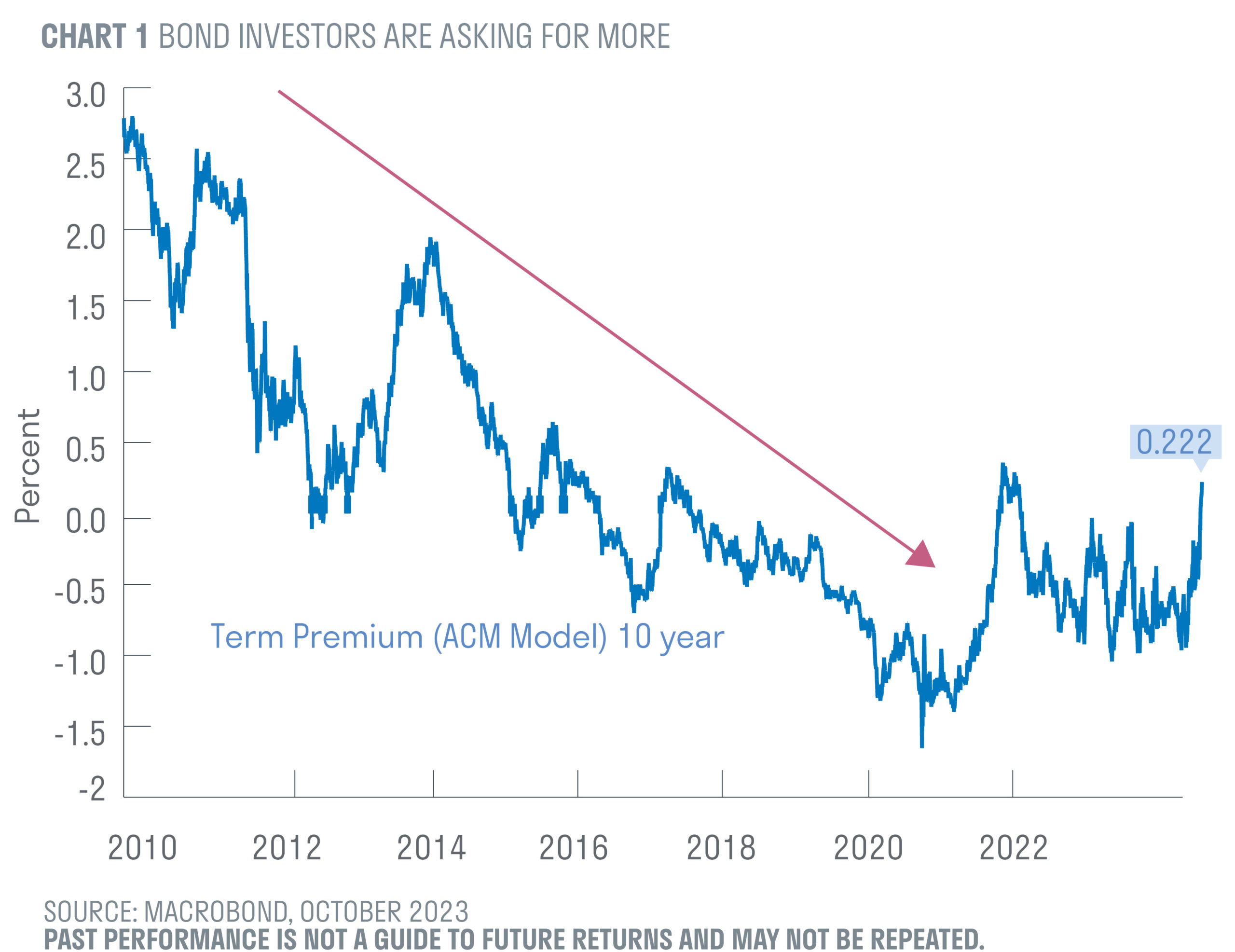

These dynamics became so powerful that many governments were able to issue debt at negative interest rates to eager buyers (see chart 1) and by 2021 $18 trillion of global debt had negative yields.1 The bond vigilantes might have become a footnote in economic history had it not been for the powerful economic shock delivered by the pandemic.

Pandemic + Ukraine = critical juncture

In economics, critical junctures are big events that have the potential to materially alter the trajectory of the world economy. The confluence of Covid-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will likely prove to be a critical juncture.

Firstly, the magnitude of these two shocks dramatically altered governments’ willingness to increase their intervention in the economy. What started as temporary income support for people affected by government-mandated shutdowns metamorphosed into a longer-term industrial policy aimed at improving global supply chain resilience.

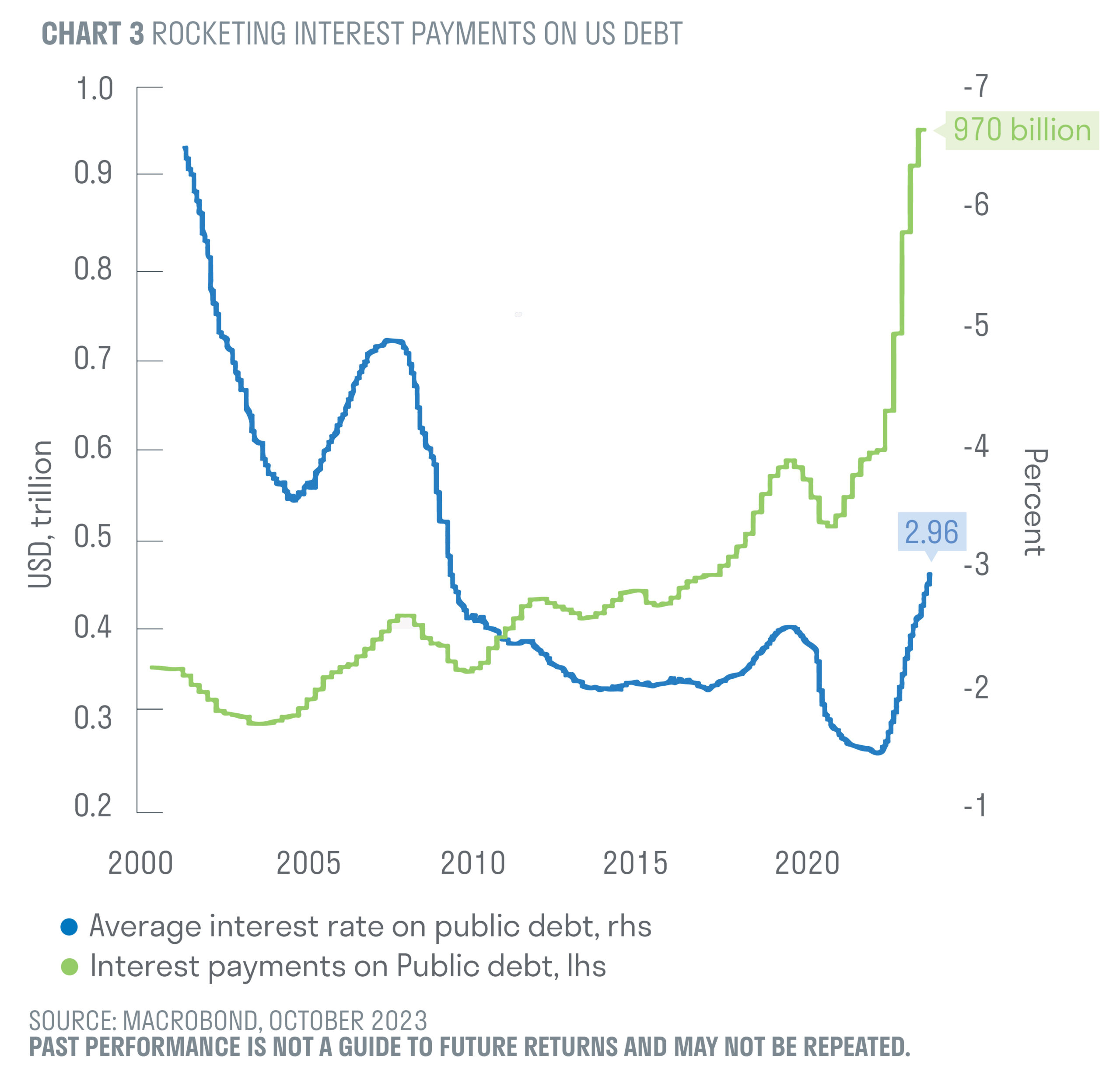

The result is an expanded role for the state that will be difficult to reverse. The US fiscal deficit is running at close to 6%, a shockingly large number for a peacetime economy. According to the Congressional Budget Office, fiscal deficits in excess of 5% will be the norm over the next few decades unless politicians shift course radically.

Moreover, with debt levels already high, the interest burden is starting to bite. The total interest cost of US federal debt is expected to reach $1 trillion this year. Both Republicans and Democrats appear to have abandoned any pretence of debt sustainability, forgetting that sustained increases in debt and deficits can swamp private demand.

Second, many businesses have used discombobulated supply chains as an opportunity to pass on price increases to households. Pent-up demand from the pandemic and accumulated household savings played an important role in stoking inflation, but dislocations in global supply enabled companies to shift their pricing strategies. They will be reluctant to relinquish this pricing power and may be more willing to raise prices if further disruptions occur.

Third, central banks, who were accustomed to ignoring smaller supply shocks, misjudged not just the magnitude and persistence of the pandemic distortions but also the resilience of household demand. A tardy initial response has led to an aggressive catch-up in interest rates, and central banks have little room for error. To maintain their credibility and anchor inflation expectations, they will need to err on the side of caution: 2024’s mantra ‘higher for longer’ is the corollary of 2021’s insistence that inflation was ‘transitory’.

Hoist by their own petard

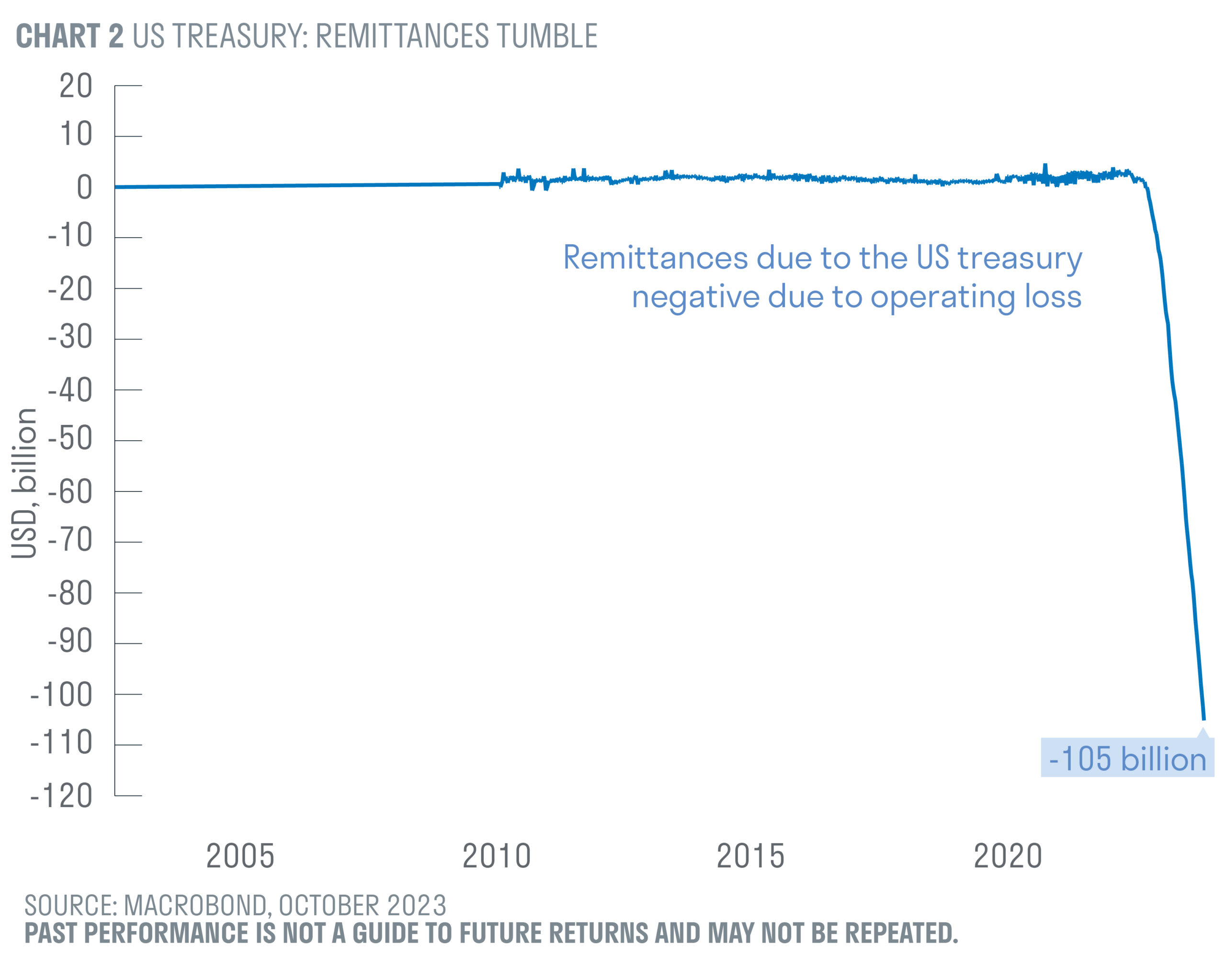

Sustained higher rates have consequences for central banks themselves. The US Federal Reserve is paying 5.38% in interest on $5.5 trillion of liabilities (bank reserves and money market reverse repurchase agreements). At the same time, it is receiving interest income from assets that were acquired when interest rates were at rock bottom. Sizeable losses are being accumulated. Since September, the US Federal Reserve has run an operating loss that now exceeds $100 billion and could easily double in a year’s time.

In addition, the sharp increase in longer-term yields mean that central banks’ balance sheets are suffering substantial losses on the market value of bonds they hold. In the US, these losses stood at $1.1 trillion at the end of 2022; since then further interest rate rises will have increased this figure.

While the Fed accounts for unrealised losses as a ‘deferred asset’ with limited near-term impact, such losses will reduce their appetite for further balance sheet expansion. In other words, the ‘central bank put’ – the notion that central banks will ease policy to support markets at times of stress – cannot be relied upon.

In the UK, policymakers are facing up to the reality that crisis interventions carry a fiscal cost. Bonds purchased by the Bank of England in its quantitative easing programme are housed at an Asset Purchase Facility (APF) backed by the UK Treasury. Between 2009 and 2022, as bond yields fell, the APF transferred £123.8 billion of profits to the Treasury. As bond yields have risen from 0.5% in 2021 to over 4.5% this year the Treasury will need to make whole any losses at the APF.

Over the next three years, this is expected to cost the Treasury roughly £120 billion. It is no wonder that central banks are pushing on with bond sales to reduce their balance sheets even as yields rise.

Over the next three years, this is expected to cost the Treasury roughly £120 billion. It is no wonder that central banks are pushing on with bond sales to reduce their balance sheets even as yields rise.

Where next for bond yields?

In the post-pandemic world, supply and demand dynamics in global bond markets have taken a markedly different tone. Governments are issuing bonds to fund ambitious fiscal agendas, with little regard for whether this is sustainable. At the same time, central banks, smarting from ‘transitory’ errors and mounting balance sheet losses, are withdrawing from their role as ‘buyers of first resort’.

Given this shift in the balance of supply and demand, and uncertainty around inflation and policy risk, investors are demanding higher compensation. As Chief Market Strategist Guy Monson explains in his article, bonds are finally offering decent real returns – but investors should bide their time.

Important information

If you are a private investor, you should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been approved by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England & Wales with registered number OC329859 which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111.

It has been prepared solely for information purposes and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the document is based has been obtained from sources that we believe to be reliable, and in good faith, but we have not independently verified such information and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

Please note that the prices of shares and the income from them can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested. This can be as a result of market movements and also of variations in the exchange rates between currencies. Past performance is not a guide to future returns and may not be repeated.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of his or her own judgment. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document. If you are a private investor you should not rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

© 2023 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP.