Governments are issuing high levels of bonds, just as central banks are keen to offload their loss-making bond holdings. Will the bond vigilantes ride back into town?

I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president…But now I would like to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.

James Carville, Bill Clinton’s campaign strategist, 1994

There was a time when bond markets wielded enormous power as guardians of the public purse. So-called bond vigilantes kept profligate politicians in check by pushing up interest rates. By the end of the 1990s even the US government started to run budget surpluses.

This changed at the turn of the millennium. First, the internet and globalisation dampened inflation before disconnecting it from the economic cycle. When the technology bubble burst in 2000, fears of a Japan-style deflationary trap gripped policymakers, who slashed interest rates.

The lessons from Japan’s decades of low growth and disinflation appeared to be clear: policy had been too slow and too timid. So when a US real estate crash unleashed the global financial crisis of 2007-08, central banks were determined not to repeat Japan’s mistakes. In coordinated moves, they slashed interest rates to zero and used aggressive bond buying programmes to bring about a faster recovery in demand

The global hunt for yield

In the wake of the global financial crisis, substantial and synchronised central bank bond purchases dramatically reduced the supply of safe assets in the global economy. At the same time, western manufacturers’ efforts to slash costs by moving production overseas gathered pace.

The result was a glut in global savings caused by current account surpluses across Asia and a drop-off in investment demand in developed economies. With excess savings chasing increasingly scarce safe assets, a global hunt for yield sent interest rates ever lower.

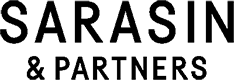

These dynamics became so powerful that many governments were able to issue debt at negative interest rates to eager buyers (see chart 1) and by 2021 $18 trillion of global debt had negative yields.1 The bond vigilantes might have become a footnote in economic history had it not been for the powerful economic shock delivered by the pandemic.

Pandemic + Ukraine = critical juncture

In economics, critical junctures are big events that have the potential to materially alter the trajectory of the world economy. The confluence of Covid-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will likely prove to be a critical juncture.

Firstly, the magnitude of these two shocks dramatically altered governments’ willingness to increase their intervention in the economy. What started as temporary income support for people affected by government-mandated shutdowns metamorphosed into a longer-term industrial policy aimed at improving global supply chain resilience.

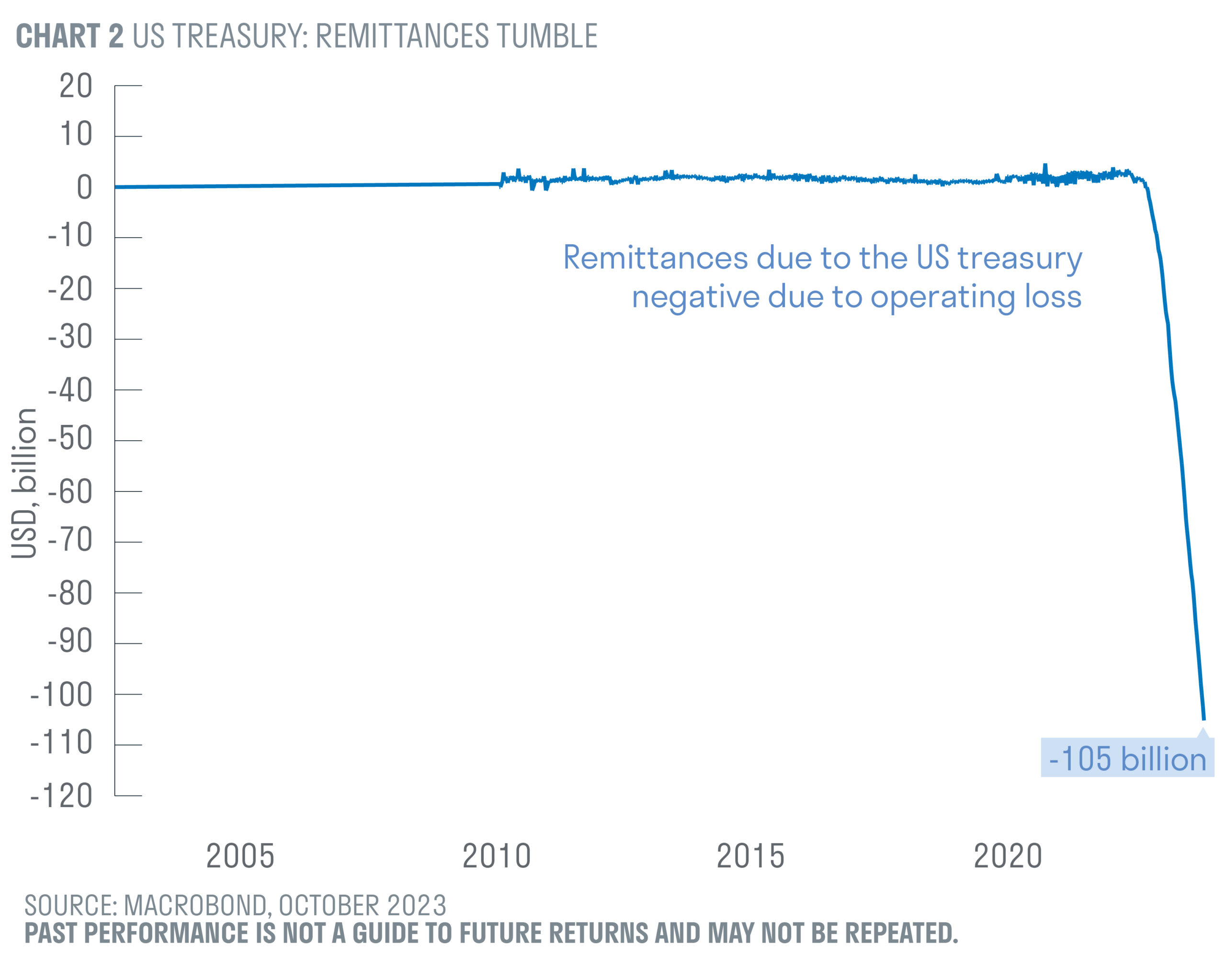

The result is an expanded role for the state that will be difficult to reverse. The US fiscal deficit is running at close to 6%, a shockingly large number for a peacetime economy. According to the Congressional Budget Office, fiscal deficits in excess of 5% will be the norm over the next few decades unless politicians shift course radically.

Moreover, with debt levels already high, the interest burden is starting to bite. The total interest cost of US federal debt is expected to reach $1 trillion this year. Both Republicans and Democrats appear to have abandoned any pretence of debt sustainability, forgetting that sustained increases in debt and deficits can swamp private demand.

Second, many businesses have used discombobulated supply chains as an opportunity to pass on price increases to households. Pent-up demand from the pandemic and accumulated household savings played an important role in stoking inflation, but dislocations in global supply enabled companies to shift their pricing strategies. They will be reluctant to relinquish this pricing power and may be more willing to raise prices if further disruptions occur.

Third, central banks, who were accustomed to ignoring smaller supply shocks, misjudged not just the magnitude and persistence of the pandemic distortions but also the resilience of household demand. A tardy initial response has led to an aggressive catch-up in interest rates, and central banks have little room for error. To maintain their credibility and anchor inflation expectations, they will need to err on the side of caution: 2024’s mantra ‘higher for longer’ is the corollary of 2021’s insistence that inflation was ‘transitory’.

Hoist by their own petard

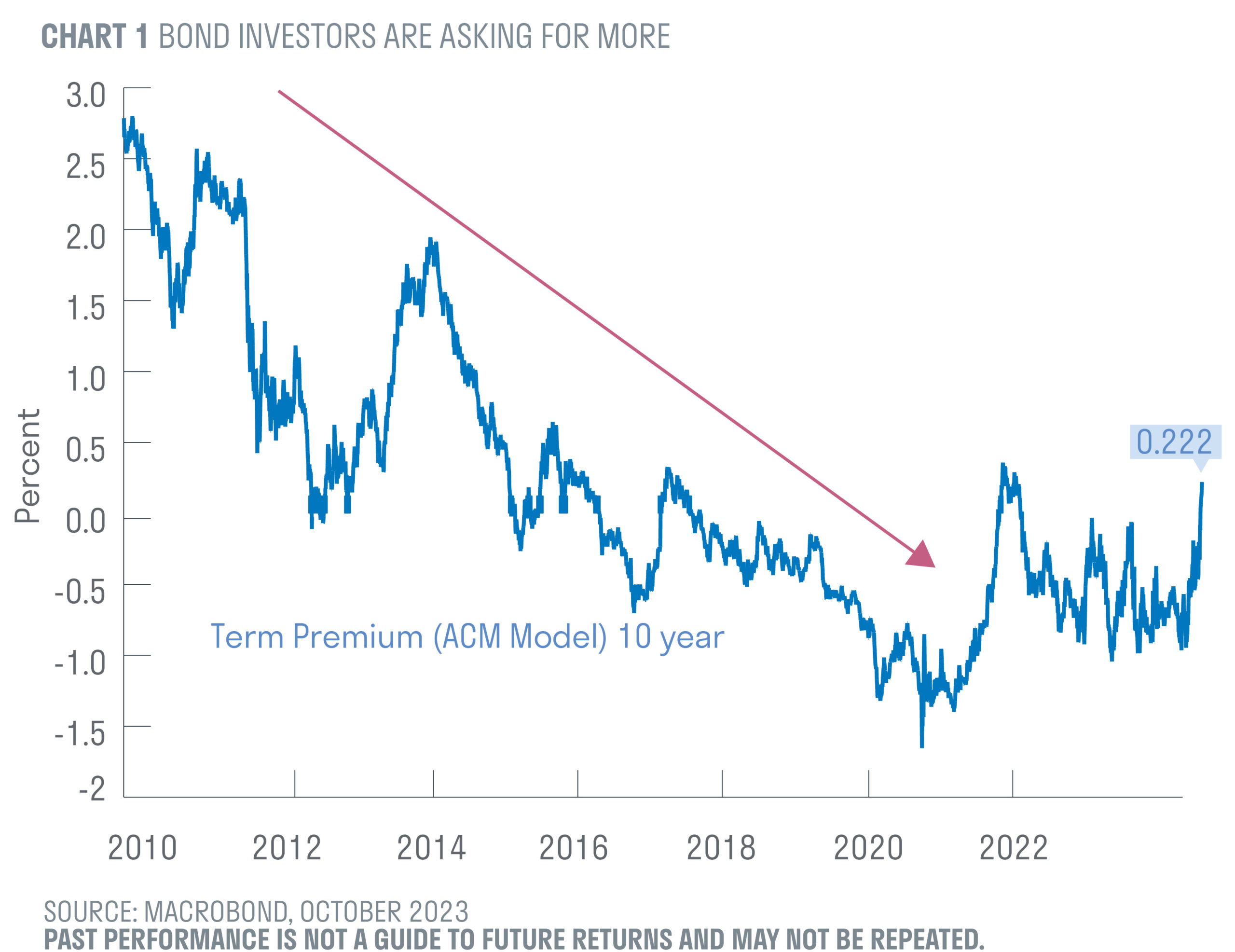

Sustained higher rates have consequences for central banks themselves. The US Federal Reserve is paying 5.38% in interest on $5.5 trillion of liabilities (bank reserves and money market reverse repurchase agreements). At the same time, it is receiving interest income from assets that were acquired when interest rates were at rock bottom. Sizeable losses are being accumulated. Since September, the US Federal Reserve has run an operating loss that now exceeds $100 billion and could easily double in a year’s time.

In addition, the sharp increase in longer-term yields mean that central banks’ balance sheets are suffering substantial losses on the market value of bonds they hold. In the US, these losses stood at $1.1 trillion at the end of 2022; since then further interest rate rises will have increased this figure.

While the Fed accounts for unrealised losses as a ‘deferred asset’ with limited near-term impact, such losses will reduce their appetite for further balance sheet expansion. In other words, the ‘central bank put’ – the notion that central banks will ease policy to support markets at times of stress – cannot be relied upon.

In the UK, policymakers are facing up to the reality that crisis interventions carry a fiscal cost. Bonds purchased by the Bank of England in its quantitative easing programme are housed at an Asset Purchase Facility (APF) backed by the UK Treasury. Between 2009 and 2022, as bond yields fell, the APF transferred £123.8 billion of profits to the Treasury. As bond yields have risen from 0.5% in 2021 to over 4.5% this year the Treasury will need to make whole any losses at the APF.

Over the next three years, this is expected to cost the Treasury roughly £120 billion. It is no wonder that central banks are pushing on with bond sales to reduce their balance sheets even as yields rise.

Over the next three years, this is expected to cost the Treasury roughly £120 billion. It is no wonder that central banks are pushing on with bond sales to reduce their balance sheets even as yields rise.

Where next for bond yields?

In the post-pandemic world, supply and demand dynamics in global bond markets have taken a markedly different tone. Governments are issuing bonds to fund ambitious fiscal agendas, with little regard for whether this is sustainable. At the same time, central banks, smarting from ‘transitory’ errors and mounting balance sheet losses, are withdrawing from their role as ‘buyers of first resort’.

Given this shift in the balance of supply and demand, and uncertainty around inflation and policy risk, investors are demanding higher compensation. As Chief Market Strategist Guy Monson explains in his article, bonds are finally offering decent real returns – but investors should bide their time.

Important information

This document is for investment professionals in South Africa only and should not be relied upon by private investors.

This promotion has been approved by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England & Wales with registered number OC329859 which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 47511.

Please note that the prices of shares and the income from them can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested. This can be as a result of market movements and also of variations in the exchange rates between currencies. Past performance is not a guide to future returns and may not be repeated.

All details in this document are provided for marketing and information purposes only and should not be misinterpreted as investment advice or taxation advice. This document is not an offer or recommendation to buy or sell shares in the fund. You should not act or rely on this document but should seek independent advice and verification in relation to its contents. Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The views expressed in this document are those of Sarasin & Partners LLP and these are subject to change without notice.

This document does not explain all the risks involved in investing in the funds and therefore you should ensure that you read the prospectus and the Key Investor Information document which contain further information including the applicable risk warnings. The prospectus, the Key Investor Information document as well as the annual and semiannual reports are available free of charge from www. sarasinandpartners.com or from Sarasin & Partners LLP, Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, Telephone +44 (0)20 7038 7000, Telefax +44 (0)20 7038 6850. Telephone calls may be recorded.

Where the data in this document comes partially from third party sources the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information contained in this publication is not guaranteed, and third party data is provided without any warranties of any kind. Sarasin & Partners LLP shall have no liability in connection with third party data. Collective Investment Schemes (CIS) should be considered as medium to long-term investments. The value may go up as well as down and past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance. CIS are traded at the ruling

price and may engage in scrip lending and borrowing. A schedule of fees, charges and maximum commissions is available on request from the Manager. A CIS may be closed to new investors in order for it to be managed more efficiently in accordance with its mandate. There is no guarantee in respect of capital or returns in a portfolio. Forward pricing is used. Performance has been calculated using net NAV to NAV numbers with income reinvested. The performance for each period shown reflects the return for investors who have been fully invested for that period. Individual investor performance may differ as a result of initial fees, the actual investment date, the date of reinvestments and dividend withholding tax. Full performance calculations are available from the Manager on request. A prospectus is available from Prescient Management Company (RF) (PTY) LTD, Tel: +27 21 700 3600. Prescient Management Company (RF) (PTY) LTD is registered and approved under the Collective Investment Schemes Control Act (No. 45 of 2022). Registration Number 2002/022560/07. Physical address: Prescient House, Westlake Business Park, Otto Close, Westlake, 7945, South Africa.

© 2023 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP. Please contact [email protected].