Bringing inflation to heel without triggering recession is getting harder. Bond markets are starting to price in the risks.

The rise in yields across global bond markets last quarter brought home a reality that many had long suspected. Namely, that letting just enough air out of the world economy to reduce inflation without triggering recession is a difficult and drawn-out process.

Despite the sharpest interest rate rises in 40 years, core consumer prices remain high.

In the US and Europe the measure is still more than twice the central banks’ 2% target. In the UK it is more than three times.[1] Central bankers may not raise rates much further, but they are still a long way from cutting them.

The ‘higher for longer’ mantra for rates has been repeated by the Federal Reserve (Fed), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of England (BoE) over the past two months. The bond markets appear to be listening. Ten-year US treasury yields climbed more than 0.7% over the third quarter to 4.5% (the highest since 2007), while in the eurozone yields rose by about 0.45%.

Even Japanese bond yields climbed after the Bank of Japan relaxed its yield curve control programme. Interestingly, one market that proved relatively defensive was UK gilts, where yields stayed at around 4.4%, after a sharp sell-off earlier in the year.

Matterhorn or Table Mountain?

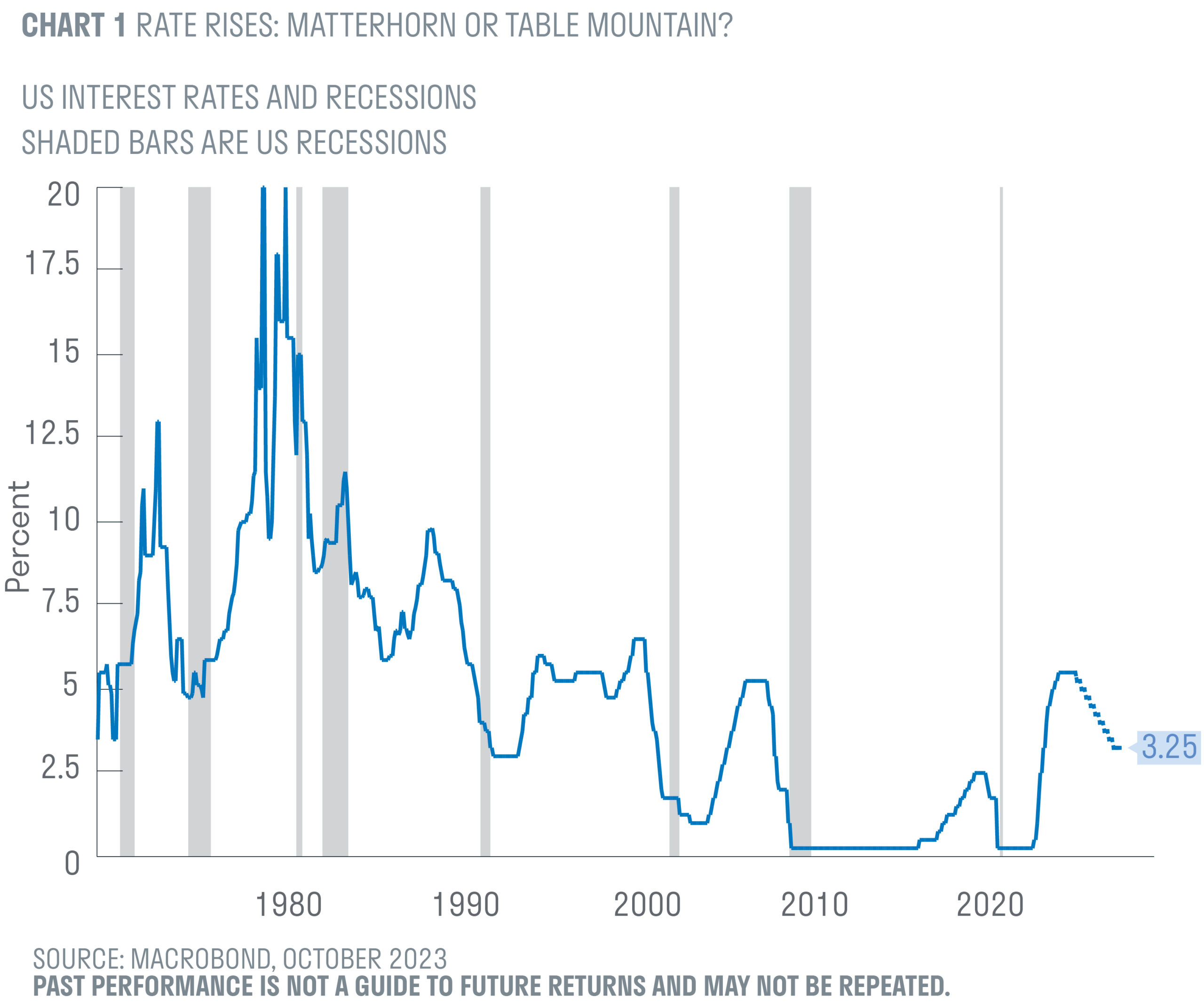

It’s important to remember that a ‘higher for longer’ strategy is not the norm for central banks. When rates peak, they talk of patient and gradual cuts, only to slash them aggressively once recession appears on the horizon. Indeed, bond traders have an old adage that interest rates ‘take the stairs up and the elevator down’, an observation borne out in almost every slowdown since the early 1970s (see Chart 1).

This time, the world’s central bankers seem determined to hold rates near current levels, at least until the second half of 2024. Huw Pill, Chief Economist at the Bank of England, recently described the traditional rate cycle as being like the Matterhorn: a long climb up and then a sharp descent. What we need today, he said, is something more like Table Mountain (he was speaking in Cape Town), where rates move up sharply but stay flat for a protracted time.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell delivered a similar message at the Jackson Hole conference in August, saying the Fed would “hold policy at restrictive levels until we are confident that inflation is moving sustainably down toward our objective.”

Beware premature victory celebrations

Such determined and unified policy statements are encouraging, because a recent study by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) shows that central bankers generally ease too early. After examining more than 100 inflation shocks in 50 countries, the authors concluded that in 60% of cases it took at least five years for inflation to return to target.[2] The policy failures came, almost universally, from central bankers’ ‘premature celebration’ of success. Today’s talk of ‘Table Mountain’ may be an honest reminder to investors that squeezing embedded service sector inflation out of the system will be a long job. The repricing of bonds to reflect this is beginning, we feel, to offer value.

Could higher oil prices re-energise inflation?

The second challenge for bond markets is the risk of a renewed inflation shock triggered by rising energy prices. Crude oil (WTI) rose by an extraordinary 24% last quarter but has fallen back sharply in recent days, at the time of writing. The driver for higher prices was supply cuts from OPEC+, coupled with unusually low inventory levels in the US. As ever, higher prices will trigger more supply: several non-OPEC+ nations, including Brazil, Guyana and the US, are poised to ramp up production. Russia is also lifting sales (ironically), as routes are found to avoid the G7 price caps and western sanctions.

While a squeeze higher in oil prices is possible, this run-up will likely be brief in the face of volatile supply and ongoing economic uncertainties, particularly in China. Politics will play a part too, with President Biden reluctant to see excessive price rises at the pump in an election year.

Unions demand a catch-up in real wages

A third challenge for bond investors is the unions’ determination to recover the multi-year losses in real wages suffered by their members. In the UK we are still facing substantial wage demands from the health and rail sectors. In the US, the United Autoworkers Union (UAW) is, for the first time, striking at all of the three biggest US producers (GM, Ford and Stellantis). The UAW is demanding a 36% increase over four years, to catch up with past sub-inflation awards – and, they say, to emulate the pay rises enjoyed by their CEOs.

There are risks that the UAW action could spread to other industries, but we should remember that US unionisation is low. Membership has fallen from 20% of the workforce in 1983 to 10% at the end of 2022. US wage growth appears to be slowing, despite the strikes, from 6.7% in June 2023 to 5.3% and vacancies are also starting to fall.[3] Labour markets are still tighter than in the pre-COVID years and strikes could escalate, but there is evidence that conditions are easing.

Bond tsunami

The fourth and final challenge for bond markets comes from a surge in supply. The reasons for this are explained in greater detail by Sarasin’s Chief Economist Subitha Subramaniam in the latest issue of the House Report in Return of the bond vigilantes?

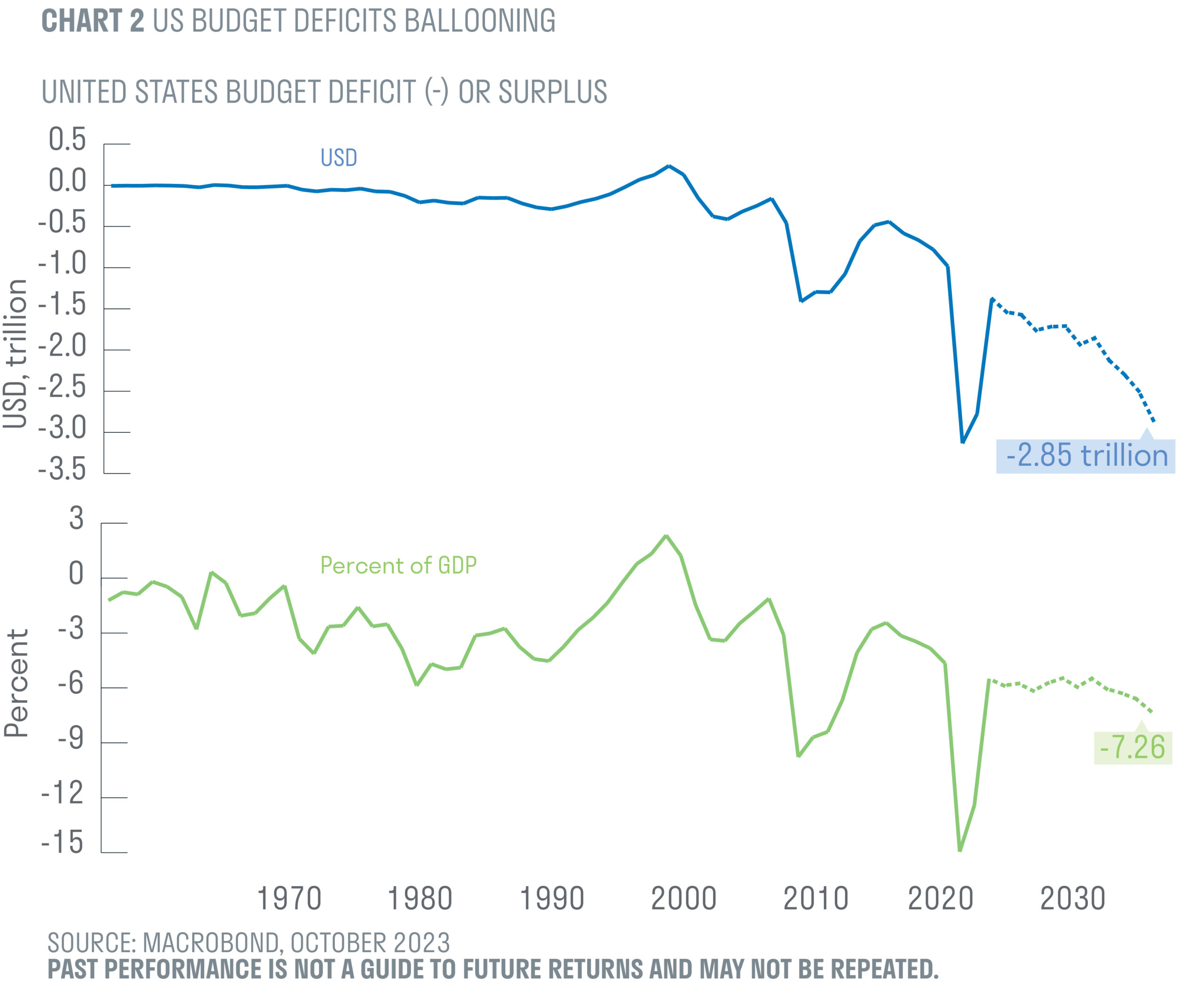

The leading culprit for the surge in supply is the Biden White House and its gargantuan fiscal programmes. The American budget deficit is running at close to 6% of GDP (Chart 2), or nearly $2 trillion per annum, a level more often associated with wartime spending. To fund this already requires enormous treasury issuance. This is not unique to the US – France and Italy, for example, have also projected materially higher deficits.

Other culprits are the central banks, which are in the process of selling vast inventories of bonds that they accumulated during the COVID years and previous quantitative easing programmes. This year the Fed is expected to sell back almost $1 trillion of bonds to the banks and treasury markets. Together, US government bond issuance and the Fed’s bond sales in 2023 will be equivalent to almost 13% of US GDP.

Daunting though this is, we must bear in mind that there is always demand for a true safe-haven asset, a US treasury, if the price is right. Today, with 10-year treasuries yielding 4.7% and US TIPS (inflation-linked bonds) delivering a guaranteed 2.4% above inflation for 30 years, rates are starting to look attractive. The more so, if inflation falls to something like the Fed’s target of 2%.

Remember, too, that high issuance does not always result in higher yields. Japan has accumulated record debt relative to GDP, yet its bonds have consistently had among the lowest yields globally. In short, issuance is a concern, but if treasuries and other government bonds are priced correctly, there will always be demand.

Farewell, TINA

For much of the past decade, ‘TINA’ (there is no alternative) has been the norm for investors. With yields on bonds and cash close to zero, or negative in much of the eurozone, equities became the default asset class.

Today, with US and UK cash yields above 5% and government bonds above 4.5%, there are compelling alternatives, particularly if you believe that today’s inflation targeting will ultimately bear fruit. I hope we have shown above that this is probable and that, despite the challenges we face, bond yields are starting to look attractive for longer-term investors.

We have already made some tentative additions to UK corporate bonds and will consider adding to government bonds and, potentially, to index-linked bonds over the rest of 2023. We do not expect to be lucky enough to pick the peak in yields but, if last quarter’s turmoil continues, we will be opportunistic buyers on some of the darker days.

[1] All data in the article sourced from Macrobond, as at 30.09.2023, unless stated otherwise.

[2] IMF, One Hundred Inflation Shocks: Seven Stylized Facts, 15.09.2023

[3] Atlanta Wage Tracker, data at 30.09.2023

Important information

If you are a private investor, you should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been approved by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England & Wales with registered number OC329859 which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111.

It has been prepared solely for information purposes and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the document is based has been obtained from sources that we believe to be reliable, and in good faith, but we have not independently verified such information and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

Please note that the prices of shares and the income from them can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested. This can be as a result of market movements and also of variations in the exchange rates between currencies. Past performance is not a guide to future returns and may not be repeated.

The index data referenced is the property of third party providers and has been licensed for use by us. Our Third Party Suppliers accept no liability in connection with its use. See our website for a full copy of the index disclaimers. https://www.sarasinandpartners.com/docs/default-source/regulatory-and-policies/index-disclaimers.pdf

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of his or her own judgment. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document. If you are a private investor you should not rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

© 2023 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP. Please contact [email protected].