On 13 December, a triumphant Boris Johnson stood in front of Downing Street to declare, “We will be bringing forward proposals to transform this country with better infrastructure, better education, better technology... We are going to unite and level up”.

Was Johnson’s declaration just another empty political slogan destined to join the long list of broken promises in the annals of obscurity? Or was it the harbinger of something more meaningful? More importantly, what does the promise to level up entail?

Levelling up promotes policies that actively seek to reduce inequality across a myriad of dimensions, all of which have increased in the last thirty years: income, wealth, generations, and rural-urban communities. In the past, reducing inequality belonged to the political left. Taxing the rich to spend on the poor was the cornerstone of left-leaning redistributive policies. In contrast, levelling-up policies embrace a broader array of tools that cut across traditional party lines. Rather than redistribution, there is a strong emphasis on pre-distribution – the notion that the state should try to prevent inequality from occurring in the first place rather than fixing it with benefits once it has occurred. Signature policies include raising the minimum wage and increasing government investment in infrastructure, education, health, and technology. The political left, seeking to remain relevant in the discussion, is pushing for even more extreme redistribution policies with wealth taxes and nationalisation of industries. As yet, such policies have not been embraced by voters.

Levelling-up policies are distinctly inward looking, favouring local over global priorities.

They are built on the belief that rampant globalisation and migration, which have exposed lower skilled workers to relentless competition from cheaper labour, have been instrumental in the real wage stagnation of lower skilled workers. Taking back control of borders in order to reduce migration is therefore perceived as a crucial first step in raising the living standards of these workers.

Levelling-up policies are gaining strength globally.

Some three years ago, Donald Trump defied the odds after running on a platform that gave voice to those that had been left behind. In his inaugural address, he proclaimed, “The forgotten men and women of our country will be forgotten no longer… We will bring back our jobs. We will bring back our borders… We will build new roads, and highways, and bridges, and airports, and tunnels, and railways…” Trump’s disruptive policies have opened the door to similar shifts globally; from Brazil to Mexico to the UK, politicians who have sought to raise the living standards of the less well-off with inward-facing agendas have reaped handsome rewards at the ballot box. In contrast, political leaders who have ignored societal inequity have faced mounting disapproval. Across Chile, Columbia, Nicaragua and Hong Kong, where there is a growing public perception that political leaders ignore societal concerns, protests against the political class are raging.

A growth tide that did not lift all boats - why levelling up matters now

Global GDP has more than doubled in the past thirty years, lifting millions out of absolute poverty. A sharp increase in the pace of technological progress and globalisation has been instrumental in the pickup in global growth. These forces, however, have also suppressed the real wages of lower skilled workers, and allowed pools of cheap emerging market labour to replace lower skilled jobs in developed countries.

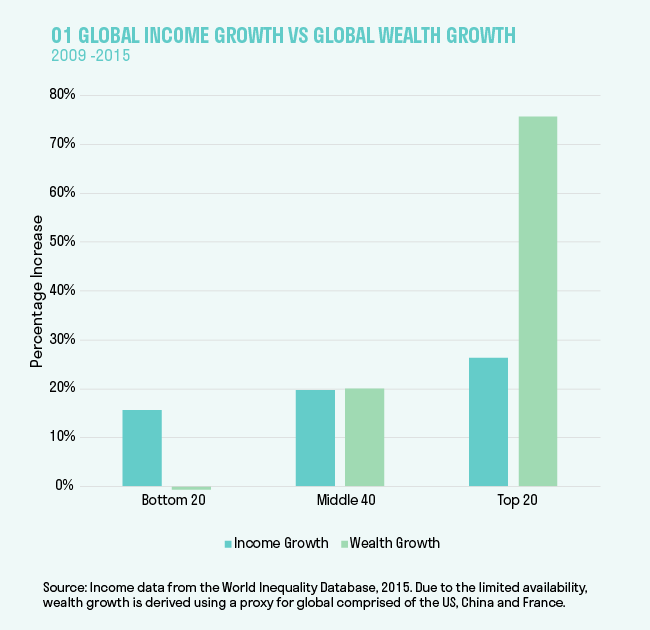

The rewards of growth have not been shared equally. In the US, in the 20 years prior to the global financial crisis, the wealthiest 10% increased their wealth by 55%, compared to the bottom 50% who only managed a 15% increase. Central banks’ quantitative easing programmes, launched as a result of the financial crisis, have led to a stark distinction between growth in income and in wealth. Central bank purchases of financial assets created the longest equity bull market in history. However, despite unprecedented levels of monetary stimulus, global growth has shifted down and wage growth has rarely meaningfully outpaced lacklustre inflation. Moreover, real wage growth for those in middle to low income jobs, often referred to as the ‘squeezed middle’, has been low and sometimes negative for many of those in the developed world. The result is that asset holders have experienced great increases in wealth, while those who rely on wages have struggled. Income and wealth inequalities have continued to widen.

The chart below illustrates the outsized benefits of wealth accumulation to asset holders since the Global Financial Crisis and start of QE.

Have your cake and eat it too!

Levelling-up policies look to raise the living standards of the less well-off without taxing away the income of the rich. This is a key difference from the redistributionists, who believe that taxing the well-off is vital to restoring parity. Levelling-up proponents shy away from such measures because they fear that redistribution invariably lowers overall growth and shrinks the economic pie. But how do the levellers propose to fund their largesse?

At the core of the levelling-up premise is the belief that governments can borrow to spend without increasing the interest burden. Proponents of levelling up believe that current economic dynamics have created the conditions for a proverbial free lunch: anchored inflation will keep interest rates low even as the government increases its borrowings, while large central bank holdings of government bonds will further mute the feed-through from inflation to interest rates. Japan’s low cost of borrowing despite a debt burden in excess of 200% of GDP serves as a reassuring example. In the eyes of the levellers, now is the time for governments to throw off the shackles of austerity and invest in its citizens.

Levelling-up proponents believe that raising living standards of the less well-off will raise overall growth rates. This is because incentives to work and invest are not compromised by punitive taxes on the rich, while investment in education, health and infrastructure raise the productivity and hence the wages of the less well-off. Levelling-up, therefore, is a promise to lift all boats and grow the economic pie.

Can the free lunch last?

For levelling up to succeed, inflation and interest rates will need to remain low even as fiscal policy steadily expands. In today’s post-crisis environment, there may be scant evidence of persistent price pressures, but, over time, a sustained increase in public debt and deficits can markedly change these dynamics. If increases in public spending do not raise the productivity of lower skilled workers, rising wages could start leaking into inflation and put upward pressure on interest rates. Central banks will face mounting pressure from their political masters to keep interest rates low. Theirs will be the unenviable task of displeasing every one: raising rates to earn the wrath of the politicians or keeping rates low to unleash stagflation.

If levelling-up policies manage to raise the productivity of lower skilled workers and the economy at large, then they could indeed unleash a rising tide that lifts all boats. Their success crucially depends upon how effective policies will be in converting investment in education, infrastructure and health into tangible improvements in productivity, output and ultimately living standards for the less well-off. For now, all we really know is that a multi-year policy shift is under way. We have ended a decade of monetary activism and are embarking upon a new decade of fiscal activism: one where the stakes are high, rewards could be rich and the risks are manifold.