Over the past few decades, investors have enjoyed the fruits of the Great Moderation – a period when the volatility of inflation and output declined steadily and economic cycles lengthened. Central banks’ management of short-term demand are credited with bringing inflation under control, but from the mid-1980s there were big contributions from long-term changes in the supply side of the global economy.

First, the coming-of-age of the Baby Boomer generation and higher female participation in the workplace expanded the labour force. These favourable demographics and social changes were then amplified by the end of the Cold War and globalisation, which brought an unprecedented flow of new workers, particularly from China and Eastern Europe, into an increasingly interconnected global labour force. Thirdly, a diffusion of new technologies around the world reduced production costs and increased productivity, providing further deflationary impetus. Demand became the limiting factor for growth, while supply appeared infinite thanks to the deflationary impacts of globalisation and technology.

Over the past few years, however, the world has been buffeted by supply-side shocks.

The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and climate change have wreaked havoc on prices, and inflation has re-emerged as a serious challenge.

While the impact of these shocks will fade over time, we believe structural supply-side shifts driven by three factors – changing demographics, slowing globalisation and increasing impacts from climate change – mean a return to the Great Moderation is unlikely and the next regime will look very different.

Staff wanted

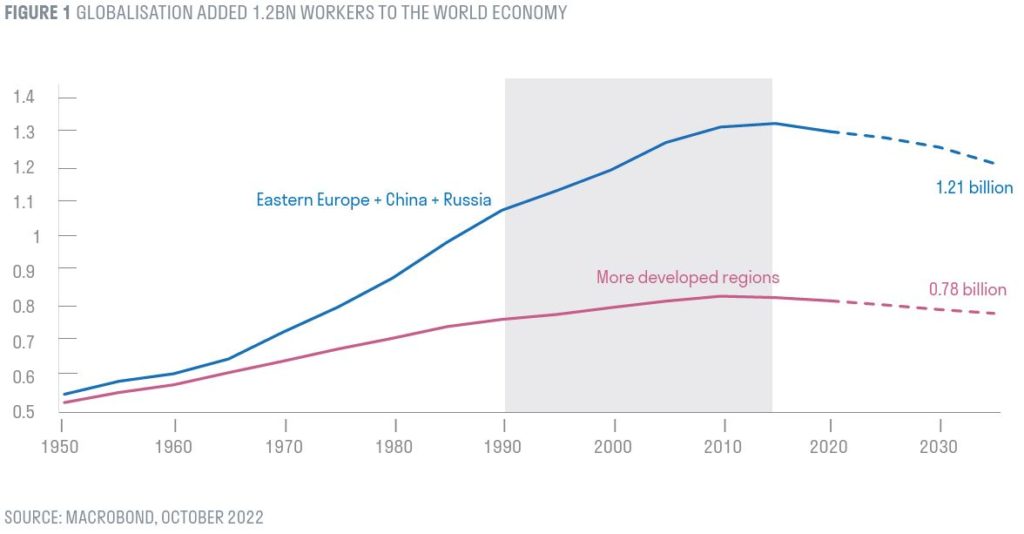

About 1.3bn new workers were integrated into the global trading economy as a result of the end the Cold War in 1990 and China’s accession to the WTO in 2001. To put this in perspective, the size of the labour pool in advanced economies was just over 800m people. The effect of this new labour pool on the global economy was dramatic – the offshoring of labour and a rapid increase in cross-border trade resulted in lower real wage growth and investment in advanced economies, offset by cheaper goods and services imported from overseas.

This rapid expansion of the global labour supply has already begun to slow or even decline, as populations in China, Eastern Europe and advanced economies age and fertility rates fall. The rising populations in India and Africa are unlikely to replicate China’s miracle of rapid integration and convergence with advanced economies due to differences in geography, culture and governance. Nor are ageing populations in developed countries likely to be fully offset by increased participation from elderly workers or immigration. In the absence of new sources of labour, the global economy will bump up against labour supply constraints.

In addition, the old-age dependency ratio in advanced economies is projected to increase from under 30% to over 45% over the next decade, and ageing in less developed regions is also projected to pick up sharply. Resources will need to be diverted to provide low-skilled, labour-intensive care for older people, reducing economic productivity and exacerbating labour shortages.

Retreat from globalisation

Escalating geopolitical tensions are a second factor constraining the global economy’s supply curve. These tensions are set to continue as China increasingly challenges the existing world order, and this strategic rivalry drives a restructuring of global trade, finance, defence and security arrangements. In this siloed, less cooperative world, finance will become more balkanised, defence spending and tariff and non-tariff barriers will increase, and businesses will bring supply chains closer to home as the focus switches from maximising efficiency to ensuring security and stability of supply.

Globalisation will likely continue, but at a much more modest pace, making supply less flexible. Weaker demographics and the re-ordered geopolitical landscape will slow the pace of convergence in emerging markets, reducing the deflationary impulse generated by emerging market productivity growth.

The heat is on

A third contributing factor is climate change, which will negatively impact the flexibility and productivity of global supply chains in two major ways.

Firstly, efforts to transition to a decarbonised global economy will necessarily include significant extra costs to companies and consumers, both to incentivise the shift towards less carbon-intensive options and to pay for the required reshaping of activity towards these more sustainable but often more expensive alternatives.

The IPCC estimates that to shift the economy onto a path compatible with limiting global temperature increases to 1.5°C would require increased investment of 0.5-1.0% of GDP every year between now and 2050. This is equivalent to 2.5% of global savings and investment over this period.

Secondly, the direct impacts of climate change are increasingly salient. While precise impacts are heavily debated, it is widely accepted that rising temperatures will have a significant, negative impact on GDP as labour productivity falls, sea levels rise and increasingly erratic weather impacts agriculture, transport and other sectors. In addition, most academic studies exclude the impacts of ‘acute events’ - natural disasters that are increasing in frequency and intensity as the climate warms. The range of outcomes are asymmetrically skewed to the downside; we know the higher the temperature increase, the more exponential the costs to the global economy.

A world of scarcity

The confluence of these factors will have multiple impacts on the fundamentals of economic growth over the coming years, most notably in the labour markets of advanced economies.

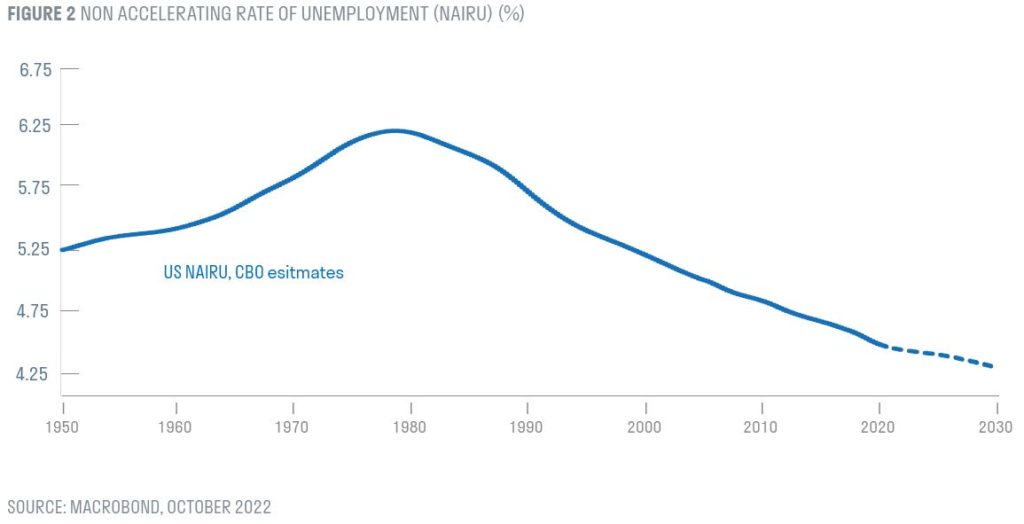

Slowing growth in the effective global labour supply and ageing populations will increase scarcity of labour in advanced economies, driving the NAIRU (non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment) higher, and reversing its multi-decade downtrend. As the NAIRU rises, the Phillips curve, an inverse relationship between unemployment and real wage growth, is likely to reassert itself once again, leading to upward inflation surprises and higher interest rates and bond yields.

Labour scarcity will have other notable effects: participation rates are likely to rise (particularly among older cohorts), people might retire much later and immigration could increase. Stronger real wage growth will see the labour share of economic value grow, likely at the expense of corporate profit margins, but could also boost consumer demand, investment in productivity enhancing automation and perhaps even reduce income and wealth inequality.

Deglobalisation and climate change will have similar effects. Slower growth in trade and a greater focus on security of supply will pressure margins, and reduce the flexibility of the supply of goods and services. While necessary, the significant costs of shifting the economy to a more sustainable carbon trajectory will ultimately fall on companies and consumers, and the need to divert a proportion of global savings towards this goal will increase the cost of capital for the wider economy. The direct impacts of rising temperatures and more frequent and intense natural disasters will also act as rolling supply shocks to the global economy.

Inflation will come down from current levels as supply disruptions fade, but we expect inflation in advanced economies to average about 2.75% over the coming decade – about 1% higher than during the pre-pandemic Great Moderation era. To match the pick-up in inflation, we expect central banks to edge up neutral policy rates. Even so, high indebtedness suggests that nominal interest rates will be held below nominal GDP levels to enable deleveraging of the global economy.

Embrace the volatility – and get more active

Investors would be wise to buckle their seatbelts and prepare for greater market turbulence over the coming years, and not expect a swift return to the smooth ride of the Great Moderation.

In this environment, traditional ‘risk’ assets will be more challenged for a period, as increasing interest rates reduces the present value of future cashflows generated from equities, bonds, property and other traditional assets.

However, some less traditional asset classes may come into their own, particularly those that target alternative return premia, such as currency carry or trend-following. In an environment of heightened volatility, risk-management investments such as commodities or option protection might also prove valuable.

Active investors may also fare better in this tougher world. While a more challenging and volatile outlook for traditional asset classes could reduce overall market returns, greater volatility increases the opportunities for active investment approaches, both in terms of tactical asset allocation and stock selection.

The ongoing correction in asset prices may be painful but is also jolting valuations back to more historically normal levels. This bodes well for investors’ future expected returns, and is creating opportunities for long-term thematic investors to build diversified, resilient portfolios for the decades to come, whatever they might bring.

Important Information

This document has been issued by Sarasin & Partners LLP which is a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859 and is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority. It has been prepared solely for information purposes and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the document is based has been obtained from sources that we believe to be reliable, and in good faith, but we have not independently verified such information and we make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to their accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

Please note that the prices of shares and the income from them can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested. This can be as a result of market movements and also of variations in the exchange rates between currencies. Past performance is not a guide to future returns and may not be repeated.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the Bank J. Safra Sarasin group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of his or her own judgment. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document. If you are a private investor you should not rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

© 2022 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP.