The UK’s departure from the European Union took effect on 31 January 2020, but for many observers the more momentous date was the ending of the transition period eleven months later, at the end of 2020.

Six months after this milestone, we take stock of the ensuing political developments, market reactions, and how this issue is likely to play out in the coming months and years.

Negotiations on this future relationship came right down to the wire, further complicated by the coronavirus pandemic, but the two sides finally reached agreement and the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (“TCA”) was formally signed on 30 December 2020. The TCA did not mark the end of negotiations; by contrast it contained a veritable web of grace periods, provisions for further negotiations, transitional arrangements, and reviews stretching out to 2030 and beyond.

A notable omission was services, which received only limited, general provisions in the agreement; this particularly impacted the outsized financial services sector in the UK, which had lobbied hard but unsuccessfully for financial services to receive special treatment. The two parties subsequently agreed a “Memorandum of Understanding” on financial services at the end of March 2021, but this is more of a starting point for further negotiations than a meaningful, actionable agreement.

In the meantime the EU has very selectively granted time-limited equivalence, meaning the ability for UK-based firms to “passport” across the EU has been severely curtailed. £900bn of banking assets (c.10% of the total) is estimated to have been shifted to the EU as a result; more eye-catchingly, Amsterdam immediately overtook London as Europe’s largest share trading venue in January 2021, although London has since narrowed the gap.

Limited short-term disruption

These provisions, reduced trade due to the pandemic, and stockpiling ahead of the deadline all contributed to the relatively low level of immediate disruption felt by the UK in January 2021; while there were some teething issues at ports as haulage firms, drivers and officials adjusted to the new regimes, fears of widespread border chaos, idle factories and bare supermarket shelves proved unfounded.

The biggest impacts were less visible; the explicit and implicit costs of extra cross-border paperwork meant some exporters of fresh fish found their business models rendered obsolete overnight, and sectors as varied as antique dealers and organisers of fashion shows complained of severe impacts from the new rules. Many other small- and medium-sized businesses found conducting business cross-border cost more, either through the direct costs associated with the additional paperwork, or the implicit costs associated with moving away from a flexible, capital-light “just-in-time” approach to a slower, more traditional model of procurement or sales.

In contrast most large, publicly listed businesses reported little material impact on their operations; the combination of well-resourced Brexit preparation teams and large, diversified pools of customers and suppliers helped keep disruption to a minimum, despite a c.20% fall total UK-EU trade, as measured by the ONS.

The macroeconomic statistics tell a similar story. The independent Office for Budget Responsibility (“OBR”) estimates that the actual impact on the UK economy to date has been relatively small; according to their analysis UK GDP in the first quarter of 2021 was only 0.5% smaller than it would have been otherwise, while their latest estimates calculate the pandemic will cause a permanent 3% reduction. They believe the impact of Brexit will compound over time as the various grace periods and transition arrangements lapse, although as businesses find new ways of working the ongoing impact should become less and less noticeable; while they forecast a permanent loss of productivity in the region of 4%, with both exports and imports reduced by 15%, roughly 40% of this loss has already been suffered.

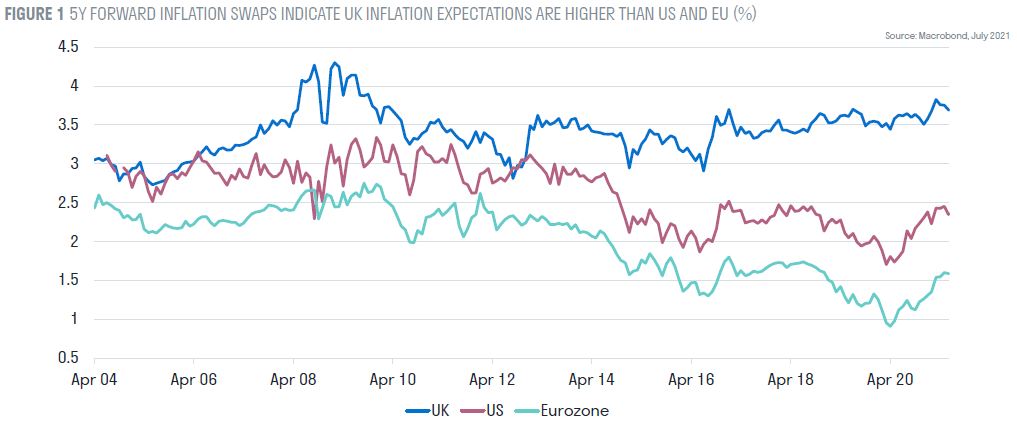

The impact of Brexit on inflation is much debated; while there is evident shortages, delays, and price increases at present across a broad swathe of goods, it is difficult to disaggregate the impacts of Brexit from the pandemic, and similar spikes in inflation are evident across much of the world. Market-implied inflation expectations have been persistently higher in the UK than in the US or the Eurozone, partly due to expected impacts of Brexit; arguably the BoE has less margin for error if the current inflation spike proves less transitory than expected, and may feel compelled to raise interest rates earlier in the economic recovery than would be ideal.

An improving political relationship?

The diplomatic or political relationship between the UK and the EU has undoubtedly been damaged by this process; the pressure cooker of negotiations held with severe time constraints and under the intense glare of the world’s media transformed admittedly very different points of view on the ideal future relationship into long lists of deeply held, often emotional grievances on both sides. Hopes that both sides could end this sorry chapter in relations with the signing of the TCA and take a pragmatic tone moving forward have proved at best premature; implementing the agreement has proved a source of constant friction, with the NI protocol proving particularly troublesome.

While both sides continue to publicly air their frustrations, behind the scenes it appears relations may have taken a more constructive turn. The UK is continuing to seek maximum flexibility in implementing checks on trade across the Irish Sea, partly due to political pressure from unionist parties in Northern Ireland, but the tone of discussions has grown more constructive in recent weeks and solutions to the various issues look possible, if not imminent; the recently agreed extension to the grace period for chilled meats is a clear sign of progress.

A possible driver of this shift has been the change in tone in the geopolitical backdrop in the last six months; the global nature of challenges like climate change, geopolitical tensions in Asia and the coronavirus pandemic, alongside a more constructive approach to diplomacy under President Biden, has seen a new, proactive attitude and energy emerge in international relations. This is evidenced by the G7 corporate tax deal, increased funding and support for the COVAX effort to provide vaccines to poorer countries agreed just in the last few weeks; all the while preparations continue to ramp up for the UN climate change conference in September this year, which the UK will host in Glasgow.

An understated market reaction

Unlike the gyrations that followed the unexpected referendum vote in 2016 and when no-deal fears peaked in 2019, asset markets responded with a metaphorical shrug to the twists and turns of negotiations during the transition period and to the actual signing of the agreement, with the global pandemic a much greater concern. The orderly exit agreed to in the Withdrawal Agreement had taken care of the worst-case implications, and markets correctly anticipated a last-minute, relatively sparse trading agreement.

UK assets have benefited from steady inflows throughout 2021 thus far, with appetite for UK assets stimulated by a number of quite disparate reasons. The reduction of political uncertainty has been a material factor, particularly for M&A transactions. The UK’s rapid vaccine rollout and associated easing of restrictions has also been very significant; although the UK suffered a more severe downturn in 2020 than most developed countries, it is currently expected to bounce back harder and faster in the second half of 2021.

Finally, the characteristics of the UK market are well-suited to the profile of the recent strength in equity markets; UK stock market indices are particularly weighted towards large, global companies in unloved sectors, which are benefiting from the global rotation away from highly valued, long duration growth stocks (like the technology sector, where the UK is relatively less-represented). Fixed income markets tell a similar story; demand for corporate bonds in previously unpopular sectors has recovered strongly in anticipation of the economic recovery, and although government bond yields remain at extraordinarily low levels considering the state of the public finances and the prospect of rising inflation, UK government bonds continue to offer significantly higher yields than those on offer in the Eurozone, and so demand remains robust.

What’s next?

After years of tortuous negotiations, the UK exit from the EU was ultimately a relatively orderly affair. While the news cycle has mostly moved on, these negotiations are likely to continue to regularly flare up into newsworthy headlines, particularly around the contentious issue of Northern Ireland, but it is unlikely the agreement will unravel or that relations will deteriorate to anywhere close to the lows of recent years.

Events, particularly the pandemic and US change of administration have had a big influence. Although both sides have indulged in political point-scoring during the pandemic, both sides would tacitly admit that the respective debates over border policies, vaccine procurement, timetables for easing restrictions etc would not have been edified by the UK’s continued presence as an unhappy member of the EU. The new US administration’s energetic enthusiasm for multilateral solutions to global problems, in marked contrast to his predecessor, has further incentivised both sides to try to build a more constructive, if more distant, diplomatic relationship going forward.

All of these developments have been positive for UK assets, and the outlook looks much brighter today than during the lows of autumn 2019, when an acrimonious, no-deal exit from the EU looked increasingly possible, or the dark days of the pandemic in spring 2020. Going forward, the impact of Brexit will be much less significant than how the pandemic plays out, how the economy responds to easing of restrictions and ending of government support, and the eventual path of growth, inflation, interest rates, and government finances, although productivity and GDP growth is likely to be slightly lower, and inflation slightly higher, than a counterfactual future where Brexit hadn’t occurred.

Was the whole exercise worth it, and which side “won” the negotiations? These points will surely be debated for decades to come, and brings to mind the apocryphal quote attributed to Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai when asked in the 1970’s if he believed the French revolution c.200 years earlier had been a success; he reportedly answered “it’s too early to tell”.