This article has been co-authored by Jeneiv Shah, Global Equity Portfolio Manager, and Colm Harney, Investment Strategist/Portfolio Manager.

Key points

- The competitive environment in the consumer staples sector is shifting. Profit pools are moving towards retailers and away from branded consumer goods manufacturers, particularly in food.

- Private label brands are becoming a lasting part of everyday shopping, not just something people switch to in hard times.

- Within our Evolving Consumption theme we continue to prefer innovators and companies with sustainable competitive advantages.

Our Evolving Consumption theme examines how shopping habits change as generations, culture, and technology shift. [1] One area we are interested in is the rise of own brands (private labelled products), which we believe is symptomatic of a change in the dynamic between retailers and branded consumer goods manufacturers, and a change in the investment opportunity set.

For many years, own brands were mostly a basic, cheaper option that gained market share in hard times and faded when consumer confidence returned. That pattern is changing. Retailers sell own brand ranges that compete on quality and choice, not just price, providing consumers with a compelling value proposition. Think Kirkland Signature at Costco, Finest at Tesco, Taste the Difference at Sainsbury’s, and bettergoods at Walmart.

Retailers are closer to the consumer than ever before. They have a growing abundance of information on customers' shopping habits as a result of the increasing use of online grocery shopping and loyalty programmes. This data is valuable for manufacturers to help inform product innovation, pricing and brand positioning, especially when their own sales volumes have been sluggish for some time and retailers’ own-brands have become a genuine competitor.

Since 2019, own brands have grown their share of US packaged goods spending led by food, where shoppers are switching into private label frozen, dairy, and snack lines.[2] Outside of food the picture is mixed. Home care and general merchandise own brands have edged their share higher, while the share of private label health and beauty products remain close to, or below, pre-pandemic levels.

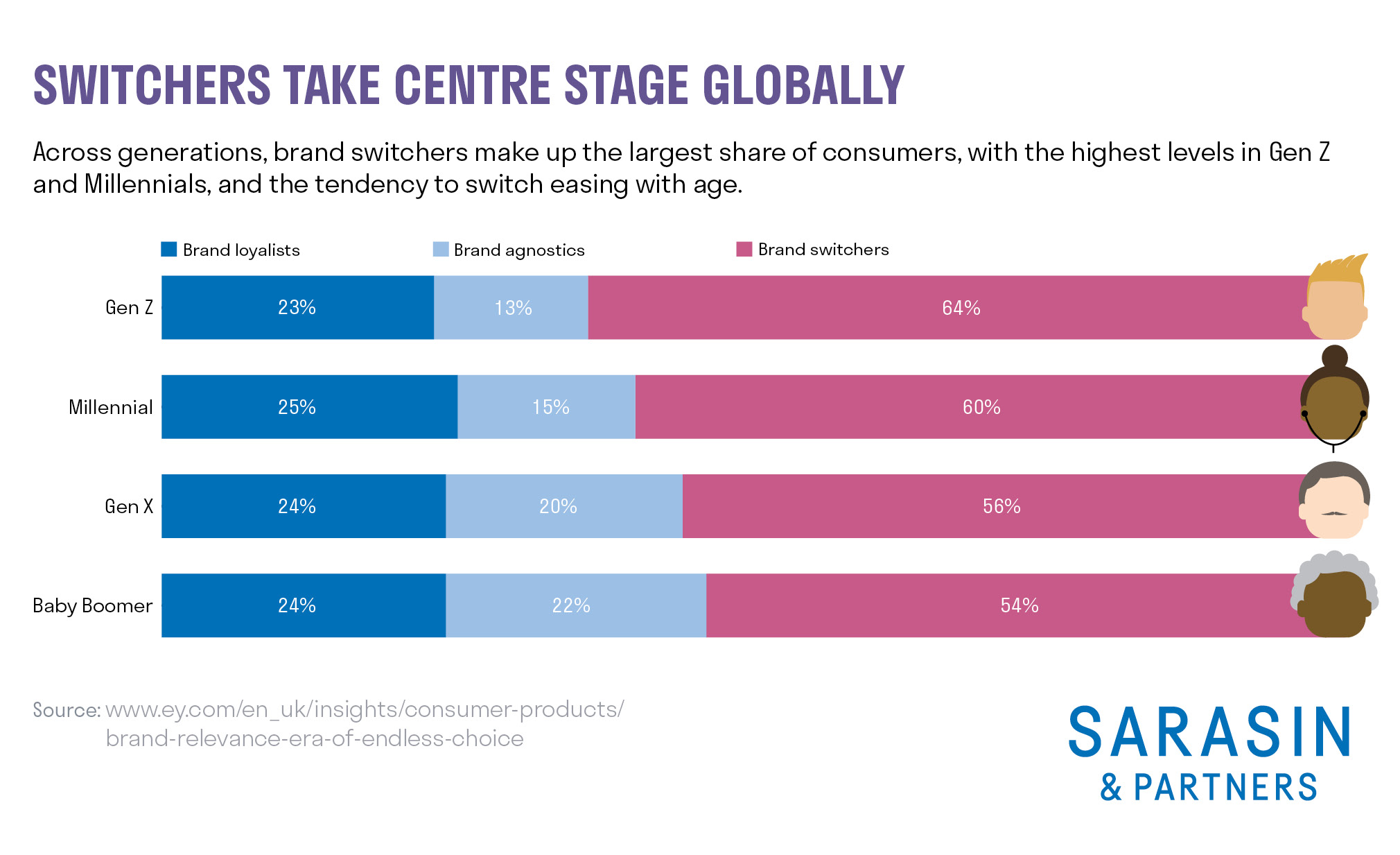

Demographic shifts have added momentum. Younger shoppers are less attached to the incumbent brands that older consumers are loyal towards. Millennials and especially Gen Z consumers are happy to try alternatives discovered through online reviews and social media. Many higher income households have increased their purchases of retailer own brands too. This marks a shift in behaviour. Frugality carries increasing social equity among consumers tired of inflation.

A further evolution is the lowering of information barriers, making it easier for new entrants to advertise and consumers to switch between brands. Social media, online reviews, influencers and creator content have made advertising cheaper and more scalable. New entrants can now reach large audiences more easily. That increases competition for traditional manufacturers and makes old-style national advertising less effective.

Evolving consumption in action

These changes show up in the way people find, assess and buy products. Three forces stand out today:

- More choice, easier discovery. Online shopping and internet views make comparisons simple, so switching to own brands or smaller challenger brands is simpler

- Quality at keener prices. Own brands are no longer just the cheapest. Many ranges now offer strong quality and retailer-exclusive products helping to drive footfall.

- Faster product cycles. Because retailers see what sells across stores and online, they can spot trends and scale winning products quickly or sell that information to manufacturers at high margins.

Taken together, these trends mean long-established brands face greater competitive intensity due to an increased threat of substitutes from retailer own brands, and lower barriers to entry for challenger brands. At the same time, higher interest rates have made it less economical for the incumbent brands to acquire their way to growth.

How the shift shows up in practice

We can see these forces at work in how the largest retailers operate. The following three examples show how own-brand ranges, shopper data, and fast-growing retail media are shaping pricing, loyalty and profits:

- Walmart's own-brand is bettergoods. Launched in April 2024, it is the company's first new food label in around 20 years, covering frozen, dairy, snacks, drinks, pasta, soups, coffee, and chocolate. Early surveys suggest a positive reaction across income groups, which supports the idea that own brand is no longer just a cheaper substitute but also a competitive alternative on quality grounds. Combined with an average nationwide delivery time of 43 minutes for online grocery orders in the US, Walmart is offering consumers both cost and time savings; a formidable combination. By the end of 2025, Walmart will be able to deliver products to 95% of US households within three hours.[3]

- Costco’s Kirkland Signature own-brand has become a bastion of high quality at attractive prices across, food, clothing and general merchandise. It helps the company keep prices low for members while offering strong alternatives across household and food lines. It supports loyalty without the need for heavy advertising.

- Ahold Delhaize has long been a leader in own-brand products. It plans to raise own-brand’s share from roughly 38% to about 45% by 2028, supported by convenience factors such as providing meal kits in store.[4] That should add value for shoppers and strengthen discussions with suppliers across Europe and the US.

Where the pressure shows up

As own brands scale and smaller challenger brands proliferate, the competitive pressure does not fall evenly across categories. Packaged food is facing some of the toughest conditions. Branded sales volumes remain soft despite promotions, while own brands continue gaining share. Packaged food demand is also pressured by the

increasing use of GLP-1 medication, aggressive price increases since the pandemic, and growing scrutiny of ultra-processed foods among consumers and policymakers. Food categories in the middle aisle of a supermarket that do not require refrigeration, such as dried pasta, sauces, and cereals, are most exposed.[5]

Household and personal care is more resilient than food but not immune. Some product leaders use promotions effectively to hold or grow volumes despite own-brand competition; others are losing share to private label alternatives even with deeper discounting. In part this has been due to a lack of focus on innovation among the branded consumer goods companies since the pandemic. Consumers do not feel it is worth paying extra for the branded product for marginally improved performance compared to own brands.

Overall, the old 2000 to 2020 pattern – modest price increases, some volume growth, and margin improvement as fixed costs were spread over more sales – is likely to be harder to replicate moving forward. The competitive intensity for manufacturers has increased. Retailers are offering consumers attractively priced and positioned own brand goods, especially in food. A higher cost of competing puts market expectations of margin expansion at risk among the owners of weaker brands, especially those in thematically disadvantaged consumer staples categories such as packaged food.

We expect many brand owners will need to allocate more resources to product innovation to rebalance consumers’ lost sense of value-for-money when paying a premium for branded goods. Manufacturers will also need to reassess marketing strategies as the return on investment in traditional media channels reduces. We suspect some of this budget will get reallocated to social media influencers and paying for prime positioning on retailers' online and physical real estate.

ESG and stewardship angles

These shifts also raise practical stewardship questions, which guide our engagement with companies:

- Fair value and access. Own brands can widen access to healthier, more sustainable options at lower prices. We ask for clear labels and responsible nutrition claims across these products.

- People and productivity. New ways of working in logistics and stores can reduce waste and physical strain, but they also change the skills needed. We engage on safe adoption, reskilling, and fair treatment.

- Packaging and waste. Own brands give retailers the scale to standardise recyclable or lower-impact packaging. We look for credible targets and progress.

How we are positioning portfolios

These insights inform where we place capital, and we put our view to work in three ways. First, we prefer retailers with dominant market share and leading e-commerce businesses, which provide opportunities to monetise memberships, marketplaces, advertising space, and customer insights to manufacturers.

Second, we are selective among brand manufacturers. We are careful of categories where own-brand exposure is high and discounts are rising without clear improvement in sales volumes or product innovation. We prefer areas with more durable advantages, such as select parts of household and personal care and beauty where proven product superiority helps maintain loyalty among consumers.

Third, we watch discounting trends as a live stress test. In non-food, heavier discounting has recently slowed own brand gains. In food, where discounting has eased, own brands are still taking share. We do not expect this trend to reverse as consumer confidence improves, unlike in past cycles.

It is worth noting that Sarasin has long taken an interest in this development between retailers and brands in our Food & Agriculture Opportunities Fund, a specialist fund that has consistently had limited exposure to conventional packaged food manufacturers.[6] More recently, it has benefited from sizable holdings in retailers such as Walmart, Ahold Delhaize, Shoprite and Costco.

Smarter shopping calls for smarter investing

We believe the direction of travel is clear: own brands are no longer just a trade-down for hard times. In many aisles they are becoming part of everyday, smarter shopping, helped by changing demographics, easy access to information and retail platforms that blend stores, websites, data and advertising.

Within our Evolving Consumption theme, we continue to be selective across manufacturers, supporting real innovators and durable category leaders, and avoiding areas where own-brand pressure is rising and discounting is doing the heavy lifting.

[1] https://sarasinandpartners.com/about/why-thematic/

[2] RBC Capital Markets, Is this private label cycle different? (18 October 2024)

[3]https://www.foodbusinessnews.net/articles/28446-bettergoods-is-turning-into-big-business-for-walmart

[4]https://newsroom.aholddelhaize.com/ahold-delhaize-introduces-500-new-own-brand-products-in-central-and-southeastern-europe-region/

[5]https://agribusiness.purdue.edu/2025/03/31/glp-1-adoption-and-its-impact-on-food-demand/

[6]https://sarasinandpartners.com/fund/sarasin-food-and-agriculture-opportunities/

Important information

This document is intended for retail investors and/or private clients. You should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been issued by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859, and which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111.

This document has been prepared for marketing and information purposes only and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the material is based has been obtained in good faith, from sources that we believe to be reliable, but we have not independently verified such information and we make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

This document should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

The value of investments and any income derived from them can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. If investing in foreign currencies, the return in the investor’s reference currency may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results and may not be repeated. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of their own judgement. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document.

Where the data in this document comes partially from third-party sources the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information contained in this publication is not guaranteed, and third-party data is provided without any warranties of any kind. Sarasin & Partners LLP shall have no liability in connection with third-party data.

© 2025 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP. Please contact [email protected].