Governments are borrowing too much money. The party ends in a hangover; the question is how severe and who pays?

Bigger government deficits were required after the financial crisis when the private sector was deleveraging and demographics were holding down inflation. But the world has now changed. Higher inflation and real interest rates will persist.

US government debt – the world’s supposedly risk-free asset – has been stripped of its triple-A credit rating. Several European economies, including Italy and France, have been forced into debt programmes to curtail their borrowing habits. China’s government is borrowing heavily to paper over weakness in its economy. In 2022, the Truss government's borrowing plans blew up the UK government bond market.

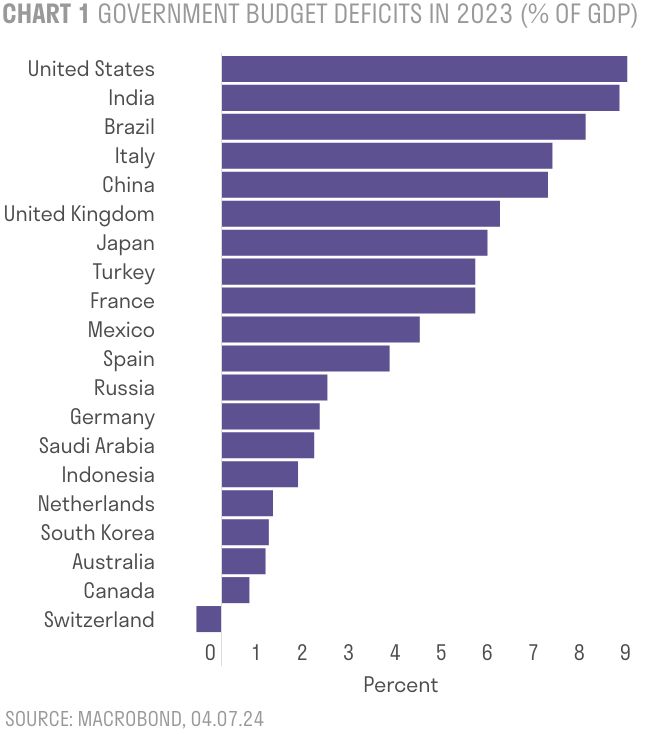

Growing government deficits are a well-established trend

Public debt and deficits surged to unprecedented levels in recent years due to emergency response measures during COVID and the war in Ukraine.

Governments increased spending to support healthcare systems, provide financial aid to individuals and businesses and stimulate economic activity. The idea was right, even if a little overdone in hindsight. The issue with emergency measures is usually the phasing out or lack thereof. Four years after the start of the pandemic, government borrowing remains significantly higher than it was beforehand. Much of the fiscal consolidation expected globally in 2024 hinges on these emergency measures being fully removed.

But the reality is government deficits have been growing for decades in both advanced and emerging economies. The world’s two largest economies – the US and China – are the main culprits behind the trends. The longer-term nature of the issue becomes clearer when we exclude interest payments on debt.

Decades of falling interest rates had concealed the true extent of the future repayment problem. Because interest rates fell well below the rate of economic growth prior to COVID, governments could in theory continue to borrow every year without seeing an increase in their debt-to-GDP ratios. Borrowing was never a free lunch, but this was the time for governments to borrow and invest. We received the borrowing, but not the investment.

Funding permanent promises with temporary savings

After trending downwards in the 1990s, government spending relative to GDP has generally been increasing since. China, the UK and Japan stand out as showing the strongest upward trends amongst major economies. In China, the ratio of government spending to GDP has more than doubled from 15% to 35%, though it still remains below the average of advanced economies at around 40%.

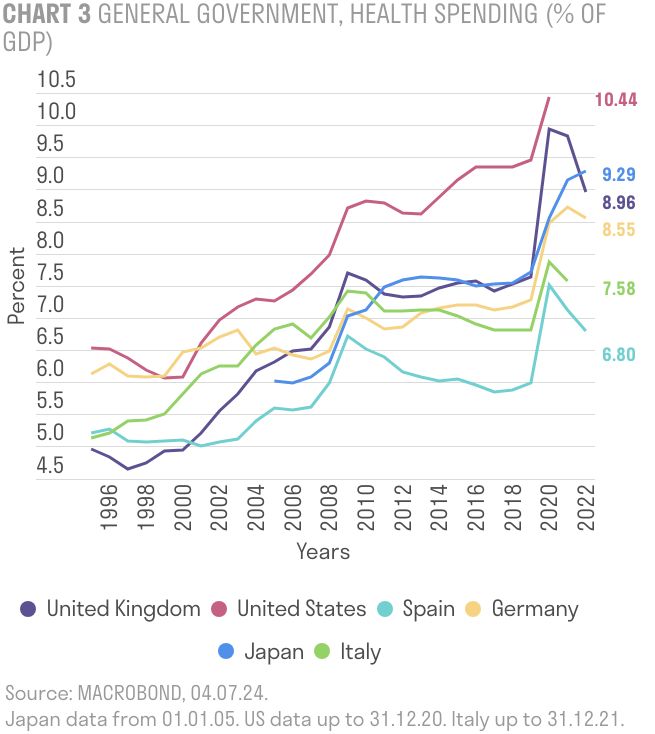

The underlying composition of spending suggests this big spending trend will continue. Governments have postponed public investment to below replacement rates in some cases, implying shrinking public capital stocks. Governments took advantage of the peace dividend to lower defence spending. After the financial crisis, it was initially emerging markets, then the private sector, who were willing to buy government bonds at very low interest rates, which lowered interest payments on government debt. The unfortunate reality is that these savings turned out to be temporary and have now reversed. The increasing healthcare and other social spending that they funded are not going away without difficult decisions.

Governments are also bringing back old industrial policies of subsidising favoured green and strategic industries. Don’t count on spending declining in an election year.

Wanting more for less

Over the past two decades, tax revenue has not kept pace with higher spending in many economies. Raising taxes has consistently faced resistance across countries despite people asking governments to do more. Tax debates generally focus on who wins and loses rather than how to raise money without reducing incentives to work, save and invest. The path of least resistance for many governments over the past few years and going forward is to raise revenue quietly through tax bracket creep, whereby inflation pushes incomes into higher marginal tax rate brackets.

The US election will have big implications for taxes. The Democrats are planning to raise taxes on high-income earners and businesses. This is possible, but the economic cost of raising that revenue increases non-linearly with the tax rate. In contrast, the Republicans are planning to cut income taxes and hope to offset some of that lost revenue with higher tariffs. The US enjoys a unique privilege to borrow big as the global reserve currency, but even this might test the bond market if inflation and real rates remain stubbornly high.

No easy way out

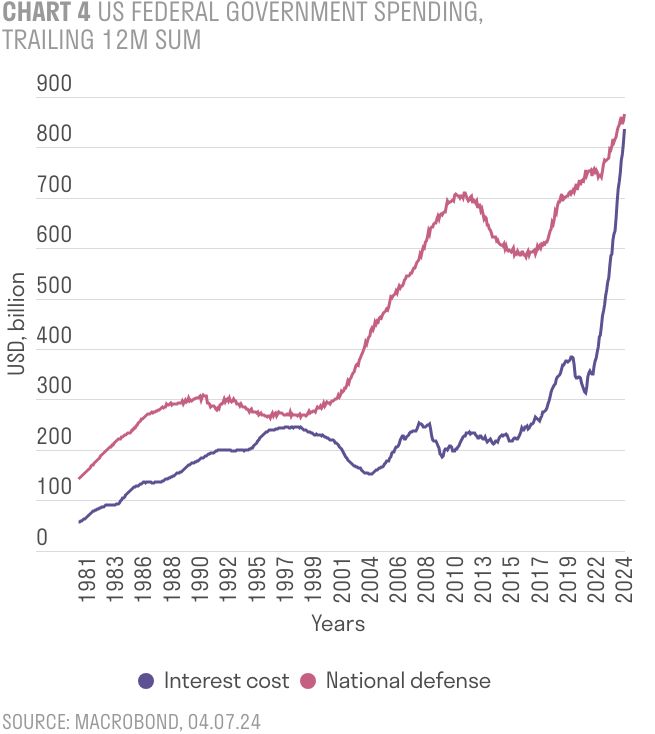

Governments can no longer rely on low interest rates to grow their way out of debt. In recent years, this differential between interest rates and economic growth has narrowed unfavourably. This means that the cost of servicing debt consumes a larger portion of government revenues, leaving less room for other expenditures. The Congressional Budget Office in the US is forecasting that just under 20% of tax revenue will be spent on paying interest costs, up from 10% just two years ago. It is about to exceed spending on defence.

So, who pays?

Significant spending cuts are politically challenging, especially this year. A multi-year plan to limit spending growth in real terms is likely, hoping to make headway before the next recession or crisis hits. Targeted tax increases are likely, particularly those that remove arbitrage opportunities between capital and labour income. Tax revenue will continue to rise quietly through inflation and tax bracket creep. All this suggests slow progress on reducing deficits.

Central banks will also decide who wins and loses. A tough central bank which controls inflation will squeeze parts of the economy not favoured by government industrial subsidies, such as small businesses and tourism. That is already happening in the US. Savers will be rewarded over borrowers for the first time in many years.

That is unless political pressure mounts to let inflation creep up. This would erode the real value of government debts (and other debts for that matter) but hurt savers, bondholders and those workers pushed into higher tax brackets. The process works best for governments if it happens by surprise. The extra return over cash for locking up money with the government for the long term remains fairly low given these risks. Equities tend to benefit from surprise strong nominal growth, especially if they have locked in extended low borrowing costs.

If pushed too far, bond buyers may revolt, as seen with the Truss government in the UK, where unrestrained borrowing plans led to market turmoil. Such a scenario could see a sharp increase in borrowing costs, forcing abrupt and severe fiscal adjustments. These crises tend to strike when the economy and people need the government the most.

With slow progress on reducing deficits expected and some risk of surprise inflation, a tilt toward equities and gold over the longer-term bonds of big-spending governments is sensible. For bonds, focus on UK corporates where demand from UK pension funds is likely to continue.

This document is intended for retail investors and/or private clients. You should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been issued by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859, and which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111.

This document has been prepared for marketing and information purposes only and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the material is based has been obtained in good faith, from sources that we believe to be reliable, but we have not independently verified such information and we make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

This document should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

The value of investments and any income derived from them can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. If investing in foreign currencies, the return in the investor’s reference currency may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results and may not be repeated. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of their own judgement. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document.

Where the data in this document comes partially from third-party sources the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information contained in this publication is not guaranteed, and third-party data is provided without any warranties of any kind. Sarasin & Partners LLP shall have no liability in connection with third-party data.

© 2024 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP. Please contact [email protected].