Key points:

- European leaders have recently committed significant sums to infrastructure and defence spending, though the economic impact of this is likely to be modest in the short term.

- A willingness to act now is encouraging, though this must be followed up with concerted efforts to tackle the continent’s structural issues.

- Our strategic allocation is to show caution on government bonds, while equities are viewed through our thematic lens.

European leaders are looking to fiscal expansion, but structural problems in the region remain.

Europe has rediscovered the allure of big fiscal spending. After decades of cautious budgeting, European leaders are suddenly opening their wallets, committing billions for infrastructure improvements and a significant jump in defence budgets. Germany, typically conservative on public spending, is leading. Berlin plans a 10-year, €500bn infrastructure initiative [1] and promises substantial boosts to military outlays. Elsewhere, the European Commission proposes borrowing €150bn [2], potentially rising to €800bn, to fund defence across member states.

Is this the beginning of a new chapter of European economic exceptionalism? Can Europe turn the apparent loss of the US security guarantee into a productive defence industry? Or is all of this spending just adding to an already bloated government footprint in the economy? These big questions must be answered as the global trading environment becomes increasingly hostile.

Germany’s infrastructure gap

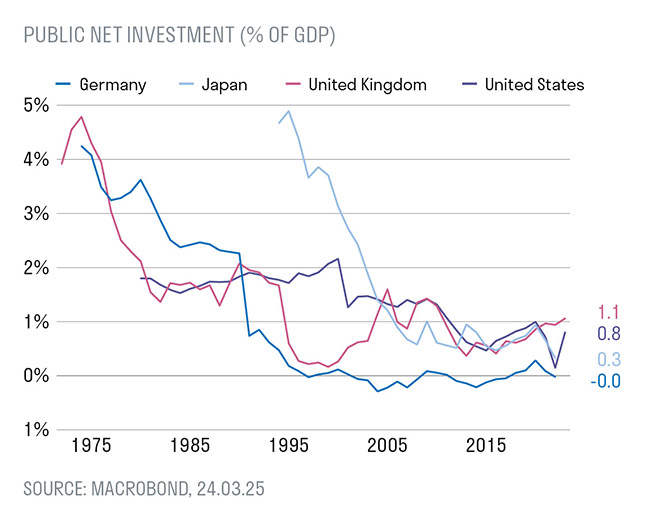

Germany’s roads, bridges, railways, and digital infrastructure suffer from years of neglect and underinvestment. Public investment net of depreciation has been zero for 30 years and well below other similar economies.

The German government’s proposed €500bn infrastructure fund (about 1% of GDP per year if spent evenly over 12 years) addresses this very problem. Better infrastructure, in theory, boosts productivity by reducing transport and operating costs and by encouraging businesses to invest. Clearly it should be prioritised but we shouldn’t overstate the long-run productivity benefits. Germany's current stock of infrastructure capital stands at around six times GDP. The planned investment might slightly lift this ratio to 6.1 times.

For reference, the Office for Budget Responsibility in the UK recently estimated that the UK public infrastructure spend announced in the October 2024 Budget of 0.6% of GDP [3] (just over half the German amount in annual terms) boosted productivity growth for the UK by about 0.05 percentage points annually over the next five years.

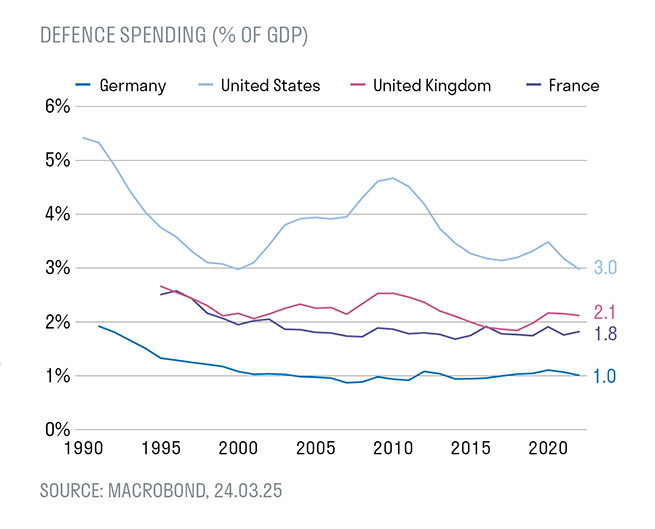

The defence imperative

Europe is also facing increased pressure to strengthen its military capabilities. Russia's ongoing war in Ukraine, instability in the Middle East, and doubts about the reliability of America’s NATO security umbrella have shifted priorities sharply. Defence spending, previously low across Europe, is now being excluded from government budget deficit calculations to loosen fiscal constraints. The European Commission’s proposed subsidised loans would help fiscally stretched countries up their spending.

Germany, a perennial NATO laggard, now spends 2% of its GDP on defence [4]. While no official target has been set, Germany and other European governments collectively will likely aim for defence spending of around 3% of GDP.

However, these ambitious spending plans run into practical obstacles. European defence sectors may struggle to quickly ramp up production, leading to significant import reliance, with a material proportion of defence spending thought to be flowing out of the continent. Moreover, with governments rushing to fulfil military contracts, negotiating positions weaken, increasing procurement costs and inflation pressures. Unlike infrastructure spending, defence spending is unlikely to directly translate to a boost in productivity.

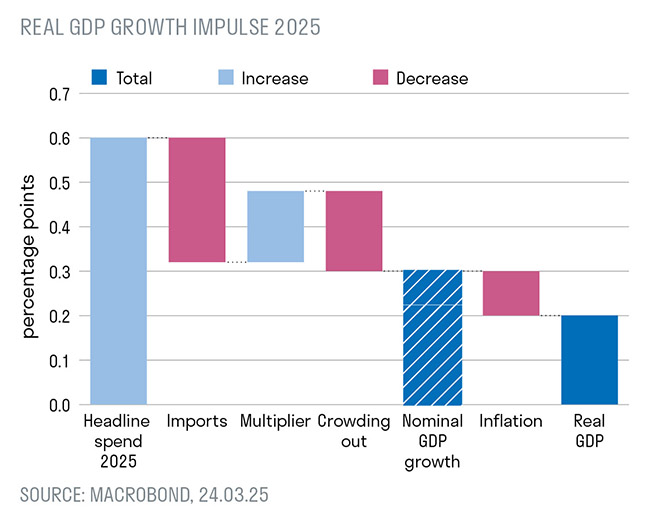

Measuring the economic stimulus impact

What will all this extra spending mean for the economy in the short term? The impact for Europe as a whole is modest. Assuming spending is phased in over three years and after considering imports – 35% for infrastructure and around 50% for defence – the net domestic stimulus for the euro area amounts to roughly 0.3% of nominal GDP per year from 2025 to 2027. Assuming a generous multiplier effect (where spending leads to further economic activity), this equates to about a 0.5 percentage point increase in nominal GDP growth per year over the next two years.

Yet even this modest stimulus may be an overestimate. Europe no longer suffers from insufficient demand of the pre-Covid world when the German government could borrow

at negative interest rates. Now inflation remains above the ECB's 2% target (the overall rate was at 2.3% in February [5]), and unemployment is low. To keep inflation in check, the ECB might counteract fiscal stimulus by maintaining higher interest rates, effectively limiting overall growth benefits. Bond yields have already risen in anticipation, and currency markets reflect this expectation clearly.

Sustained fiscal stimulus could be part of a strategy to run a “high pressure economy”, deliberately trying to coax the unemployed back into the labour force, boost productivity, and get wages on an upward path. The Biden administration in the US pursued a similar strategy following the Covid pandemic with some success, although the resulting inflation – worsened by the disruption to the global economy from the Russian invasion of Ukraine – proved unpopular with voters.

Distributional effects matter

In a non-zero interest rate world, fiscal stimulus and associated higher interest rates mostly redistributes the economic pie. While supporting defence, construction and manufacturing, increased German government spending risks crowding out private-sector investment outside of these sectors. It will also crowd out spending in other sectors

of the economy that been benefiting from the weak euro, for example tourism in periphery European economies.

More worrying is the fiscal stress it might cause. Higher bond yields in Germany could cascade into even higher borrowing costs for heavily indebted European economies like Italy and France and even the UK. This reinforces our strategic allocation to gold and suggests some caution on government bonds.

Not a cure-all: Europe's structural issues

Europe’s recent fiscal announcements reflect overdue recognition of serious problems – crumbling infrastructure and insufficient defence capabilities. This seemingly joined-up effort shows real willingness to redress some of these long-known concerns, though increased spending alone cannot solve all of Europe's fundamental economic problems. Weak productivity, ageing populations, inflexible labour markets, and outdated regulatory frameworks continue to hold Europe back. Infrastructure investment will help and should be done, and it is hard to draw any conclusions at this stage as to how successful this spending will be if the money is spent in the right areas.

The Draghi report on EU competitiveness [6], published in September 2024, outlined a plan to combat a “self-fulfilling” lack of dynamism on the continent. Three key areas

addressed by the former Italian Prime Minister: closing the innovation gap with the US and China, especially in advanced technologies; the need for a joint plan for decarbonisation and competitiveness; and for action in increasing security and reducing dependencies – the EU relies on a handful of suppliers for critical raw materials, especially China.

The recent Trump tariff announcement highlights the need to become more competitive, innovative and agile. The first-round effect of US tariffs may be a hit to EU exports. The second-round effect may be having to compete even harder with Chinese goods in global markets outside the US, and no doubt some pressure from the US to reduce reliance on Chinese inputs.

European financial markets have generally responded positively to the fiscal announcements. Defence stocks have been a particular beneficiary, this aligns with our thematic view that higher defence spending globally will be an enduring theme.

Our global, thematic approach eschews a regional approach, and seeks to find quality companies with enduring thematic tailwinds, wherever these may be found. That said, our portfolios have significant exposure to companies listed in Europe. This has been a particularly fruitful hunting ground forour Evolving Consumption theme, which contains a number of large, European-listed firms with a truly global footprint, which naturally insulates revenues from the ups and downs of the European economy. One example is LVMH, which is listed in France and benefits from worldwide demand for its luxury goods brands such as Louis Vuitton and Moët & Chandon – its clients tend to be brand sensitive, rather than price sensitive. Another Paris-listed company, eyewear specialist EssilorLuxottica, also has global reach and benefits from significant economies of scale, and the associated attractive levels of margins and returns on capital.

Our investment team will continue to identify these stock opportunities while we keep a close eye on the big picture events in Europe, and to understand the implications of the shift in fiscal policy at a company and industry level. While the US and the impact of its foreign policy has tended to dominate geopolitical discussion of late, Europe’s role as a powerful and disparate voice on the world stage is anything but diminished.

The continent stands at a critical juncture, and if it can follow through with the structural reforms needed to turn fresh fiscal spending into genuine growth opportunity, then there’s no reason why it can’t flourish – even if trade and political relations with the US turn sour. However, should policymakers underestimate this critical juncture, defaulting to familiar complacency rather than ruthlessly pursuing the required reforms, Europe’s hopeful outlook could fade.

[1] www.politico.eu/article/germanys-merz-secures-breakthrough-onhistoric-

spending-plan/

[2] European Commission proposes borrowing €150bn, potentially

rising to €800bn

[3] https://obr.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-october-2024/

[4] www.reuters.com/world/europe/germany-met-nato-2-defencespending-

target-2024-sources-say-2025-01-20/

[5] https://data.ecb.europa.eu/main-figures/inflation

[6] https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/

draghi-report_en

Important information

This document is intended for retail investors and/or private clients. You should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been issued by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859, and which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111.

This document has been prepared for marketing and information purposes only and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the material is based has been obtained in good faith, from sources that we believe to be reliable, but we have not independently verified such information and we make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

This document should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

The value of investments and any income derived from them can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. If investing in foreign currencies, the return in the investor’s reference currency may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results and may not be repeated. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of their own judgement. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document.

Where the data in this document comes partially from third-party sources the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information contained in this publication is not guaranteed, and third-party data is provided without any warranties of any kind. Sarasin & Partners LLP shall have no liability in connection with third-party data.

© 2025 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP. Please contact [email protected].