A surge in equity markets since early January means portfolios have performed strongly in the first half of 2019.

We have always held the view, however, that it is best to prepare for stormy conditions when the waters are calm. It is much easier to ensure one’s vessel is truly watertight and ready to survive the fiercest seas when the sun is shining and time is on your side.

With fears over rising interest rates seemingly behind us and bond yields once again close to their lowest levels, equities and other risk assets have risen sharply. However, we are a little concerned that there is an increasingly long list of reasons why investors could have forgotten that capital and income can not only go down, but can sometimes take several years to recover:

- We have seen 10 years of gains since the financial crisis

- The world economy has enjoyed steady growth for a sustained period

- The cost of borrowing has declined steadily, allowing investors to benefit from, and importantly, maintain, cheap debt and thus leveraged positions

- Through a variety of Quantitative Easing programmes, governments and central banks have supported asset prices

- As a result of all of the above, setbacks in markets have typically been erased quickly and volatility has gradually declined, interspersed with occasional spikes

Events have been such that we suspect some complacency has crept into investors’ mind-sets. Moreover with bond yields low, credit spreads tight, and valuations of many ‘alternative’ asset prices riding high, protecting capital in the next downturn may well prove harder than past periods of uncertainty.

While this concerns us, it is a healthy reminder as to why we place so much emphasis on investing genuinely long-term monies in volatile assets, and why we value robust and sustainable income streams so highly. Critically, while we expect future capital volatility to be as unpredictable as it has been in the past - and quite possibly more prolonged than has been the case more recently – we continue to believe that income streams will be less volatile, as they have been historically. A well-diversified income stream will prove its worth if it can be relied upon to fund the (vast) majority of current spending, both in terms of peace of mind and the ability not to be forced sellers of assets.

A key question for investors today is: how to diversify and protect a charity’s income stream?

Diversification by asset class

There are a number of diversified, multi-asset funds that either have sold their entire fixed income allocation or reduced holdings to less than 10 per cent of the portfolio. While yields on offer today for government and investment grade corporate debt are substantially lower than they have been historically, we acknowledge that the fixed interest payments of bonds remain a necessary basis of one’s income. Much the same can be said of UK commercial property, where the majority of future returns are likely to be sourced from income of 4% to 6%, rather than capital appreciation. Lastly, while we have recently taken profits across a range of alternative sources of income-oriented alternative investments such as infrastructure, renewable energy, and high yield bond and leasing structures, these can all have a place in a well-diversified portfolio at certain times in the market cycle.

In short, equities look attractively valued relative to a wide cross-section of historically defensive assets. However it would be all too easy to end up with too heavy a skew towards equities and other risk assets at this point in the cycle. Whilst managers with a high structural bias towards equities and an aversion to bonds have performed particularly well recently, we regard investment as a marathon, not a sprint. An investment horizon of 5 years is not genuinely long-term, particularly for charities. Diversification will prove its worth again in the future, particularly from an income perspective given the secure income streams that these high quality asset classes provide.

Diversification within equities

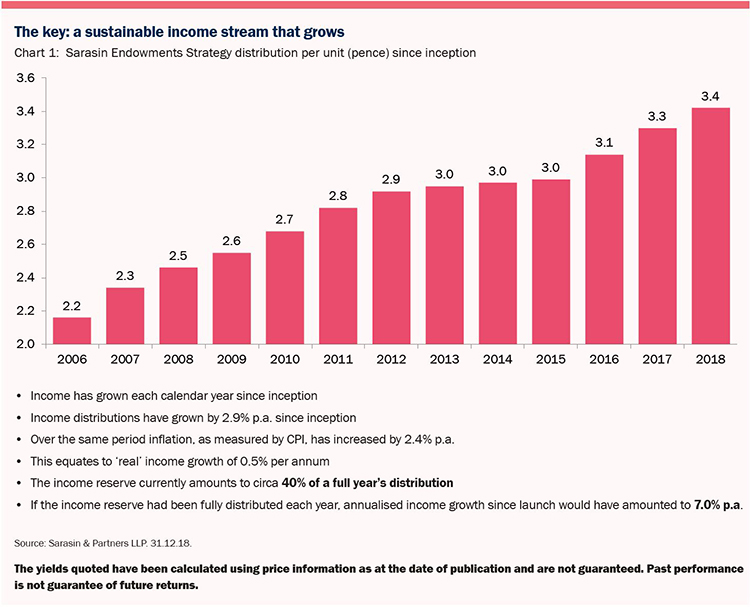

Readers may be aware that we have taken our clients on a journey towards ever more global portfolios. Most recently, we switched 10% of the our Endowment strategy out of the UK into overseas equities in February 2018. There are of course some higher yielding and attractive growth opportunities in the UK. However we see significant stock and sector-specific risks, even before we consider the current political shenanigans and a post-Brexit landscape. The pace of the journey has been set by a desire to increase our clients’ income year-on-year while concurrently maintaining a reasonable proportion of income in sterling.

While sterling has been weak ever since the referendum, a recovery to levels above $1.40 would damage income streams; a stark reminder as to why matching assets and liabilities is taught at such an early stage and repeatedly during an investor’s education. Some charities have been able to adopt a fully global portfolio and live within their means. Others are far more comfortable investing predominantly in the UK, where premium headline yields are currently available, reflecting political uncertainty. This meant it has taken us about 14 years to move from a 60% allocation to a 20% allocation, while growing income distributions each year and in real terms. We still see charity allocations of up to 50% to UK equities when analysing charity’s Reports & Accounts across the sector. This is a concern, both in terms of the dangers of a sudden drop in income or merely low levels of growth in future years.

Why the dangers in the UK? First, only a handful of companies account for the majority of the dividends paid in the UK stock market. Second, a dangerously high proportion of earnings are distributed to investors as dividends, meaning a drop in profits would be swiftly passed through in lower dividends. And the UK stock market is not well represented in sectors in which we would like to access, such as technology and manufacturing.

Option income at the margins

For many years, we have managed to add 5-10% per annum to the dividends, coupons and rent we collect by simple option writing on some of the equities we own. One needs to be a little opportunistic; returns from this source can be particularly good when volatility is high and less so when markets are gently trending upwards. However, this works rather well, given income is generally most welcome when markets are misbehaving and capital values are volatile.

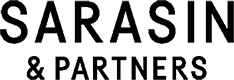

Income reserving

Where fund structures allow, even the most forward-looking manager with a well-diversified portfolio can periodically benefit from an ‘income reserve’. Specifically, there will be times when low and zero-yielding stocks look attractively valued and high yielding stocks expensive. At others, the best total return might be delivered by a wholesale switch from a higher yielding asset class (like property) into a lower yielding one (like gold or hedge funds). Lastly, building a more global portfolio (while likely to enhance income over the medium to longer term) likely results in a hit in the short term. A wise fund manager who builds up a reserve in the good times can then draw from it after making strategic asset shifts. By way of reference, the reserve within our Endowments CAIF has fluctuated between 15% to 45% of a full year’s distribution over the past 12 years. This has proved essential at times of market stress, such as in the Global Financial Crisis when bank shares slashed their dividends, or in the wake of the Macondo disaster when BP did the same. While a global portfolio with higher exposure to foreign currency income streams will always be more volatile to a UK investor; an income reserve can help smooth short-term currency volatility.

In every instance, an income reserve allows a fund manager to focus on generating the most attractive long-term total returns. This is arguably one of the greatest benefits of investing in a specialist charity multi-asset fund. Where clients have segregated portfolios, the income stream needs to be carefully managed. Regular unit trusts have to pay all of their earned income out every year so as not to muddle up their investors’ income and capital gains tax accounting. However, Charity Investment Fund (CIF) and Charity Authorised Investment Fund (CAIF) structures are permitted to roll excess income from one year to the next to ensure a smooth and consistent distribution that investing charities can rely upon over time.

Two words of warning: first, some CAIF/CIF managers have depleted income reserves which is likely to mean their distributions are less reliable going forward. Moreover, recent changes to charity law allow charity funds to top up natural income with capital. While this can make sense, charities do need to know whether they have unwittingly adopted a total return investment policy. Prudence would suggest that regular enquiries are made as to what proportion of ‘income’ distributed is actually capital. The concern is that trustees end up spending too much on current beneficiaries, finding out too late that their capital has been depleted in real terms to the detriment of the next generation.

In conclusion, while income reserving allows for an element of total return investment and helps to ensure smooth annual increases in spending, nothing is more valuable than a truly diversified income stream that proves to be reliable and sustainable the next time markets wobble for more than a just a quarter or even twelve months.