Bonds have played an integral role in investors’ portfolios for well over 100 years and were considered the asset class to own before equities threw off their mantle of being a high-risk gamble.

It wasn’t until the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s that George Ross-Goobey presented various positioning papers to the Imperial Tobacco Pension Fund Trustees, persuading them and others that a diversified allocation to equities should make up the majority of a long-term investment portfolio.

Since then, bonds have been deemed to be the lower risk, lower return foundation stones of multi asset portfolios, upon which more volatile return-seeking asset classes could be added. Relatively few investors abandon bonds entirely: historically they have produced a return better than cash and time and time again, they have proven to be a liquid safe haven in times of market stress.

However, after decades of falling inflation and ever lower bond yields, we have reached a point where the majority of investors are projecting that the low returns available on government bonds will be more than offset by inflation, resulting in negative ‘real’ total returns. This article considers whether now is the moment to abandon gilts and possibly all investment grade bonds altogether.

Low returns always?

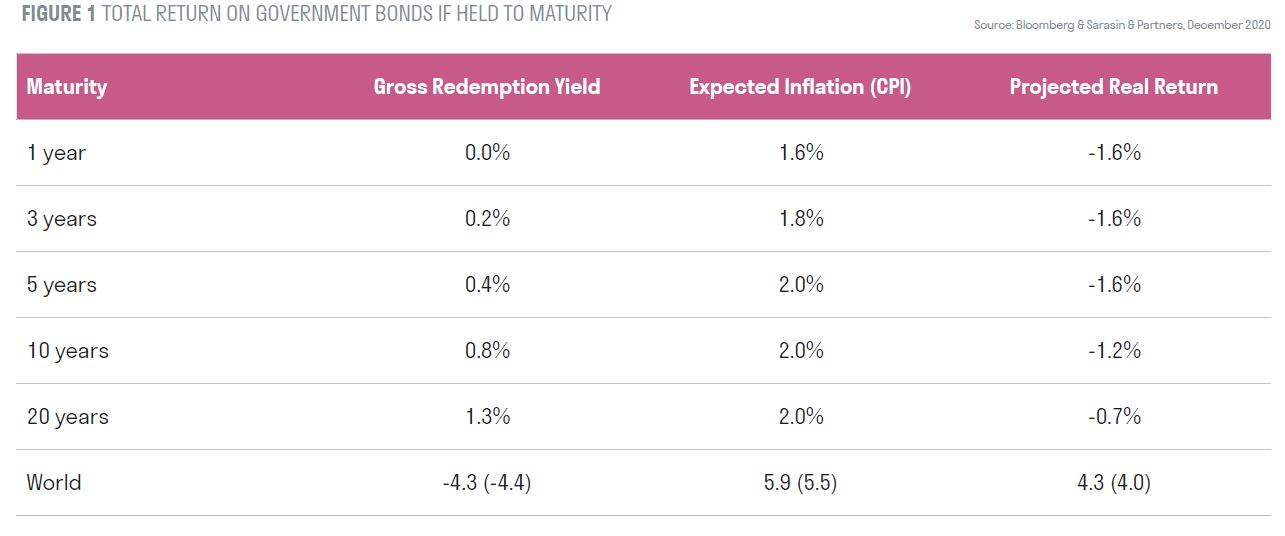

Figure 1 notes the total returns available – Gross Redemption Yields (GRY) –on UK government bonds with different maturities. There is no getting around the fact that these are extremely low absolutely and by historical standards. Take off inflation and an estimated cost of management and the results are likely to be negative. The case against owning bonds looks persuasive.

However, this presumes that the bonds are held to maturity and that we don’t care about the performance between now and then. It is entirely possible – indeed likely – that at some point in the next decade, confidence in other assets crumbles and there is a classic ‘flight to safety’. In such a scenario, bond yields might be driven lower for a period of time, resulting in higher returns. This is what happened in the first half of 2020. Gilts produced a return of +6.4% in Q1 of 2020 despite the 10-year gilt starting the quarter on a GRY of just 0.8%. This was against a backdrop of global equities falling by 16% and UK equities falling by -25.1%1.

Alternatively, forecasts for growth and recovery might be optimistic or central banks and governments might pursue even more draconian measures of financial repression. Bond yields could fall further and quite possibly turn negative, just as they have in Europe. If the 10-year gilt moved from today’s yield of 0.79% to a yield of -0.25% over the next 12 months, the total return would be +8.6%.

So, there are scenarios that would result in bonds producing attractive absolute returns and there will almost certainly be periods when gilts dramatically outperform other assets classes, even if only for brief moments in time.

Investors can also boost the sub 1% GRYs available on 10-year duration UK government issues by owning corporate bonds: we typically suggest a 50:50 split between government and corporate issues, which can be tactically skewed to favour one over the other depending on your outlook. At the time of writing, our portfolios are invested with a distinct tilt towards corporate issues which on average, should generate about 2% more per annum than their equivalent government issues.

Adding value with ESG

It is worth noting that there are three areas where we feel Sarasin adds value with our corporate bond management: our Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) research skills, our familiarity with the not-for-profit sector and our not too significant scale.

Long ago we recognised the improvement in risk-adjusted returns that can be garnered from rigorous ESG analysis, while also considering names that might be unfamiliar to the largest institutions. This motivated us to buy the Wellcome Trust’s inaugural public issue 15 years ago, a bond we hold to this day. For the same reason we entered the retail charity bond market at its inception seven years ago and similarly, we felt able to buy Vena Energy’s (an Asia-Pacific renewable energy developer) inaugural issue last year.

Vena Energy builds and operates wind, solar and energy storage projects in Southeast Asia, Australia and Japan. It has been around for nearly a decade but only issued its first public bond last year, in dollars, which we bought. The bonds have a redemption yield of around 2.5%2, which is almost twice what you’d receive on average for a 5-year BBB issue in dollars. Why is this? Mainly unfamiliarity: the issuer doesn’t have listed equity and only recently came to markets for capital. But the bonds have very strong covenants and provide security over physical assets.

Ultimately, investing in these non-traditional issuers have proved fruitful. Over the passage of time, we expect to harvest outperformance through a combination of the ‘sustainability premium’ and a growing ‘investor familiarity’ premium in smaller issues that many of the largest investment managers would find it hard to own in any meaningful size. Moreover, a significant proportion of these issuers, like Vena, have no listed equity, hence the only way for ESG-aware investors to support them is via fixed income investment.

Initial conclusions

For investors with short- to medium-term time frames, it is hard to see how gilts and high-quality corporate issues will not continue to make up the bulk of their portfolios. The inherent risk in most other asset classes will remain too much to bear. Low returns are a bitter pill to swallow, but being forced to sell volatile assets after a sharp unexpected setback, which results in losses being realised that could generate proceeds that are too small to meet the known liabilities, is probably even less palatable.

For longer term investors who are happy to forego a little return to achieve smoother and less volatile returns, UK government and corporate bonds will, in our view, continue to offer an important and liquid diversifying asset that will prove its worth as a safe haven in moments of wider market stress. That said, we have reduced the strategic allocation to bonds in our core Endowment strategy.

First, their risk-return profile has changed absolutely and relative to other asset classes. Second, we are more comfortable with the other asset classes (alternatives) and techniques at our disposal (portfolio insurance) that we can deploy to dampen volatility when compared to ten years ago. In short, government and high-quality corporate issues have less unique safety characteristics than they used to.

Of course, our endowments strategy has never been appropriate for all of our clients; we have always managed charity portfolios which, for a variety of reasons, need to take a different level of risk than that of our ‘core’ offering. While many of these require a lower risk approach, 10-15% of our charity clients feel comfortable taking more risk than our core long-term endowments strategy offers. We have always been happy to provide them with bespoke strategies that match their particular needs.

What is interesting is how this 10-15% group has developed recently: against the backdrop of the ultra-low bond yields discussed earlier, we have witnessed a clear increase in clients with genuinely long-term assets who feel it would now be appropriate to take a further step up the risk curve. A recent poll of our clients suggested that 20-25% of charity investors would now feel comfortable adopting a higher equity allocation, a higher alternatives allocation and dispensing with bonds entirely.

Our actions

Although some of our peers have abandoned bonds as a matter of ‘tactics’, we feel that giving up on an asset class that has such rare defensive credentials is not a decision to be taken lightly. We expect to guide our clients in their strategic decision making. However, while we seek discretion to make tactical tilts in asset allocation, strategic moves of this nature are something we like to discuss with our clients to make sure they are fully aware of the consequences. We believe moves of this nature should be taken in partnership between investment manager and client and never entirely left to the investment manager’s discretion.

As a result, we feel this is the right moment to introduce another CAIF to complement the Endowments and Income & Reserves strategies.

The Sarasin Growth CAIF will invest 80% of its assets in global equities with no particular UK bias. The remaining 20% will be invested in a diversified mix of alternative assets. While the strategy will have the ability to own bonds and cash, its modus operandi will typically be to look through any forecast short- to medium-term volatility. It will not seek a specific level of income and investors will need to embrace a total return approach to withdrawals, topping up the natural income stream with capital disbursements.

We did consider whether we should adopt the approach taken by some charity funds, distributing a fixed percentage sum per annum, with the split between capital and income decided by us as managers. However, we have always felt that this could result in poorly monitored capital progress and believe it important that charities can easily account for the progress of their capital and income separately. While adopting a total return approach to spending makes complete sense in these days of very low yields, we see a serious risk of real capital losses developing over time if only total returns are tracked and scrutinised.

To answer the question in the title of this article: are bonds still a strategic asset class for all long-term investors? Probably not – and we look forward to discussing the best approach for your charity over the coming weeks.

1Source: Sarasin & Partners, Bloomberg

2Source: Sarasin & Partners, Bloomberg