Few investors will reflect on 2022 with fondness. The armed conflict in Ukraine, spiking commodity prices that added a blow torch to already elevated post-COVID inflation and dramatically higher bond yields resulted in a year of volatility and negative returns.

While positive commentators will suggest matters have stabilised, uncertainty still abounds: the global economy is sluggish, conflict in Ukraine has not abated, the aftermath of China’s zero-Covid policy is still biting and corporate earnings expectations are likely to be lowered.

In summary, economic, geopolitical and reputational risks remain elevated. We have used this edition of the House Report to consider several ideas and concepts that should enhance investment resilience.

Unconstrained global investment

Many of our segregated client portfolios already operate on a global basis: we think the time has come to adopt a fully global equity allocation within our range of CAIFs. Although the UK equity market derives a high proportion of its revenues (70-80%) from overseas, these are skewed to a limited number of sectors. We believe we are most likely to meet our clients’ investment objectives via an unconstrained approach.

Moving fully global does not mean avoiding UK companies. It just means that when we allocate to UK-listed companies, it is because they have achieved their place in the portfolio on merit alone.

A fully global equity allocation appears to result in a lower exposure to sterling. However, this is optical as opposed to actual. UK-listed companies generate 70% to 80% of their revenues from overseas: investing internationally does not have a material impact on the portfolio’s exposure to overseas revenues. In the immediate aftermath of the Brexit referendum, UK-listed companies with international revenues rose in value as sterling fell. The age-old convention of showing UK-listed securities as sterling assets – even if they are inversely correlated with our local currency – results in a sterling weight of 60% in the Sarasin Endowments CAIF. However, on a ‘look through’ basis, this figure falls to 42%, which is almost identical to both the headline and look through estimate for a fully global allocation. In practice, we do not expect a significant change in the actual exposure to sterling as a result of these changes.

The benefits of diversification apply to income generation as well. In the UK, approximately 40% of all dividends come from five companies, resulting in an unpalatable level of risk. Companies that generate these dividends are also focused in a few industries. While UK dividends look attractively high, pay-out ratios are amongst the highest of all developed markets. These factors concern us.

The corollary to this is that the absolute level of income from the equity allocation within portfolios will fall. While bond yields have risen and counter this, it is likely that overall portfolio income will fall and trustees will need to consider topping income up with some capital.

Total returns and income

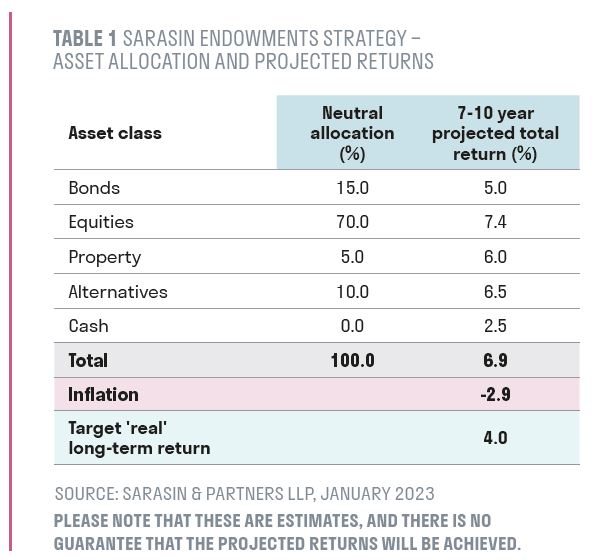

If each asset class was invested in line with the current average yields, the global portfolio we envisage would yield about 2.2% However, as table 1 draws out, this is only about half of the real – and thus expendable – total return we expect such a portfolio to generate over the longer term.

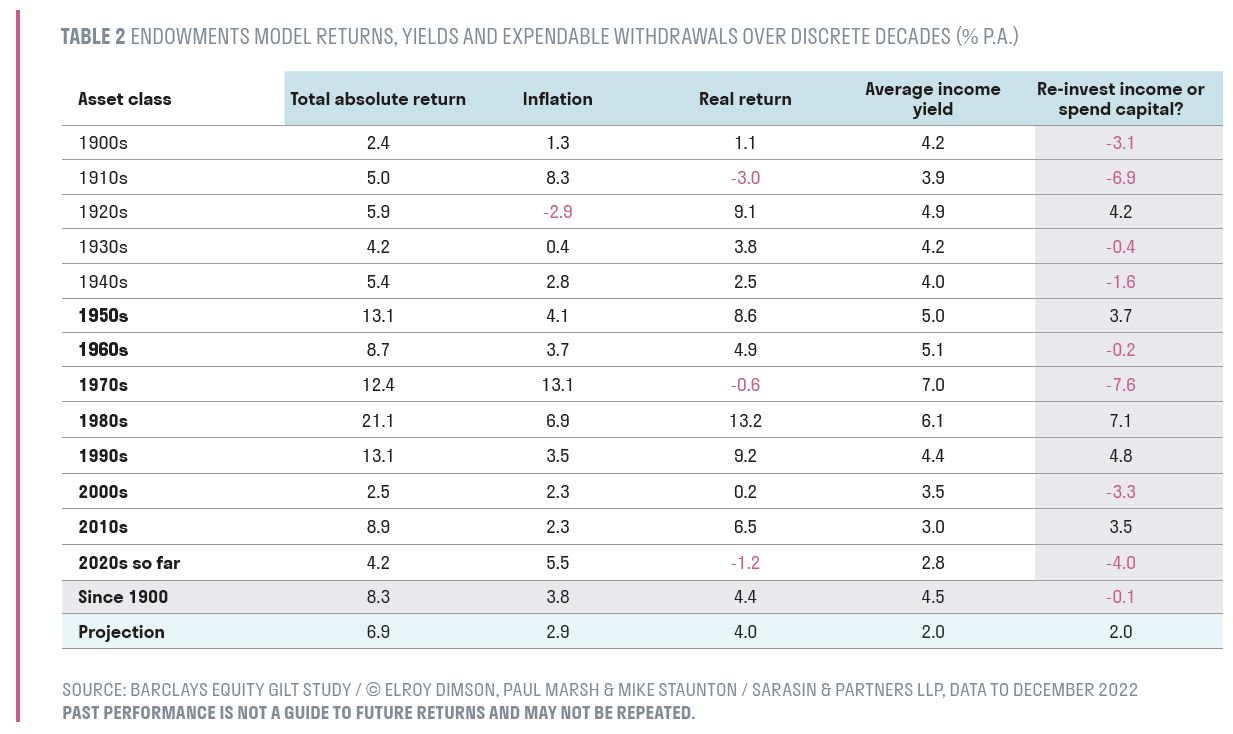

Many of our clients have already adopted a total return approach to spending: yields have fallen dramatically are now well beneath the amount that could be spent sustainably. Since 1900, we have shown in our Compendium of Investment that between 4% and 4.5% could have been spent on average each year while retaining the ‘real’ value of one’s capital. This is shown in table 2.

Table 2 also shows that before the end of the 1970s yields were so high relative to total returns that it was generally necessary to reinvest some income if capital was to retain its real value. Since the 1970s, one could have spent about 6.5% per annum, against a yield that now stands at 2%. What both ancient and recent history draws out is that attractively simple ‘income only’ spending formulas have rarely worked.

We embrace the concept of total return spending. However, we do feel that trustees should keep track of what they spend. Legislation allows managers of charity funds to distribute a mix of income and capital and The Charity Commission has stated that, from an accounting perspective, these distributions can be treated as income. Several investment managers have embraced this opportunity but we fear that trustees might not keep in touch with exactly what they are being paid. It also makes comparisons between different managers and strategies much harder.

While it might be easiest to have your manager effectively take control of your spending policy, we would suggest this is something that should be owned by trustees. We suspect there are quite a few charities invested in CIFs and CAIFs who currently believe their regular ‘income’ distributions are just that, income, or possibly income topped up with a little capital. In actual fact, the capital element might now make up 30-50% of the distribution. Is this camouflaged treatment of income fully understood?

Our conclusion is that we will not move to total return distributions for our CAIFs. It is easy to set an annual spending figure and top up natural income distributions with small sales of units over the year. In this way, an appropriate amount can be spent and each generation of trustees can track the performance and their stewardship of the capital for which they are responsible. Trustees will also be aware of the underlying income yield of the assets they own. Yields can be an important figure to analyse, with low yields suggesting over-valuation, or a significant style or geographic bias. If you are only being shown an inflated ‘income’ figure boosted by capital, have you lost sight of an important data point for historical and peer comparison?

The evolution of ethics and negative screening

We have seen a shift from negative screening towards more nuanced evaluation of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors. Whilst this can result in divestment, this is at the discretion of the manager, which can result in ownership of companies whose practices cut against beliefs central to a charity’s existence. Consequently, negative screens that forbid investment in certain sectors remain part of most investment policies. However, ethics and morals shift.

The invasion of Ukraine last year prompted many to question whether arms manufacturers should continue to be grouped with other ‘sin’ sectors? Quite a few trustees have remarked that helping fund the ‘defence of the realm’ and protecting others less fortunate shouldn’t be considered a sin. We wouldn’t expect Quaker charities to take this point of view, just as many Catholic charities avoid companies involved in the production of abortifacients. But, we suspect that some trustees might wish to reconsider what they want to avoid. Another area worth reviewing might be junk and sugary foods; whether it is best to avoid or engage with the extractive industries and whether now is the time to shine a torch on Russian and Chinese companies?

There is no definitive answer to these questions, either from a performance or ethical point of view. Where possible, trustees should make decisions based on their own specific objective and missions. However, a pragmatic approach is often required and it is worth reminding oneself that the most common restrictions do not exclude large swathes of the investible universe. From a global point of view, the five classic ‘sin‘ sectors make up no more than 5% of the MSCI All Countries World Index.

Like so much else, ‘hard’ negative screens need to be reviewed to ensure they continue to align with your charity’s particular mission. It will remain equally important to feel comfortable with your investment manager’s overall ESG Research and Evaluation Process: this will probably influence your performance more than any negative ethical screens you ask them to embrace.

Conclusions

A New Year starts with a smorgasbord of opportunities and risks. Markets are volatile and unpredictable and regularly make fools out of investors! However, a robust strategy that is well-diversified, evolves over time and is transparent in terms of income, liquidity and what one owns are all important elements in the formula for long-term success.

Important Information

If you are a private investor, you should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional advisor.

This document has been issued by Sarasin & Partners LLP which is a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859 and is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority. It has been prepared solely for information purposes and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the document is based has been obtained from sources that we believe to be reliable, and in good faith, but we have not independently verified such information and we make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to their accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

Please note that the prices of shares and the income from them can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested. This can be as a result of market movements and also of variations in the exchange rates between currencies. Past performance is not a guide to future returns and may not be repeated.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the Bank J. Safra Sarasin group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of his or her own judgment. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document. If you are a private investor you should not rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

© 2023 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP.