Long before COVID -19, the roles of capital and labour in the world economy were being fundamentally redrawn.

New technologies were virtualising and digitising a growing share of consumption, and businesses were responding by fervently substituting capital for labour in production. Even as labour markets were facing considerable disruption, the public sector remained largely on the side lines: government investment in infrastructure, education and health consistently fell behind the needs of a dynamically adjusting economy.

What has emerged is an increasingly unequal world: one where capital has gained pricing power over labour and the job market has become more polarised. These socio-economic shifts have led to calls for political change and a concomitant demand to level up. Politicians have taken note and a substantial policy shift is underway: one that is seeking to reshape and resize the role of the government in the lives of its citizens. One thing is becoming progressively clearer – if governments are to deliver on levelling up they will need to fund a more muscular public sector. Doing so will entail deeper forays into policies of ‘financial repression’ while also reshaping the financial landscape. Investors had better take note.

The productivity and inequality nexus

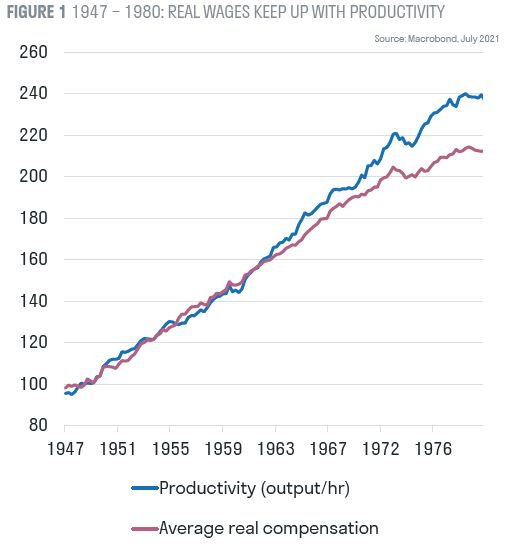

In economics, we are taught that the route to higher living standards lies through increasing productivity; better technology enables workers to raise their productivity and hence real wages. Figure 1 plots productivity in the US from 1945-1980 and during this period average real compensation mostly kept pace with productivity.

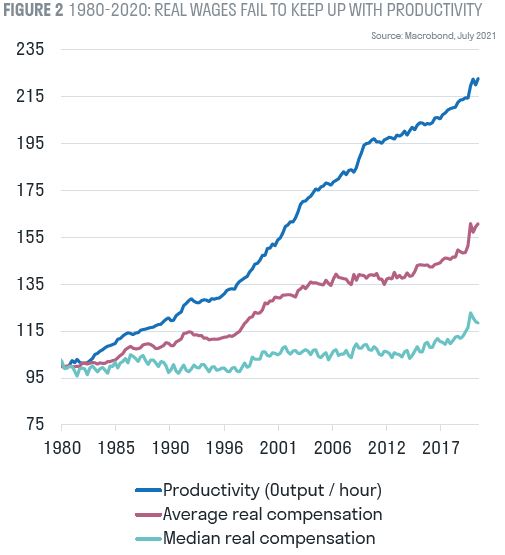

However, in the last 40 years, the relationship between productivity and wages seems to have broken down (figure 2). Productivity has increased at a much faster pace than wages. Moreover, because median wages – the wages of the 50th percentile – have increased at an even slower pace than the average, the vast majority of workers appear to not have benefitted much from the improvements in economy-wide productivity.

So, what lies behind this shift?

In a large part, the way in which new technologies diffuse through the economy appears to be changing. For example, when a new technology is adopted by businesses, workers are simultaneously displaced from old roles (by new technologies) and re-instated to new jobs. MIT economists Acemoglu and Restrepo have broken down the task content of production to evaluate how the displacement and re-instatement of jobs has evolved over time. What they find is that in the 40 years after the war (1947-87) the displacement and re-instatement of jobs mostly balanced each other and the task content of labour in production did not materially change. Technological change diffused through the economy without altering the balance between labour and capital. However, in the period 1987- 2017, the displacement of labour far exceeded the pace of re-instatement and the task content of labour in production fell by roughly 10%. In other words, the role of labour in economy-wide production suffered – labour lost power.

Another MIT economist, David Autor, has argued that the contours of the new roles that emerge as new technologies diffuse through the economy have dramatically changed in recent decades. He has found that the roles that emerged in the economy in the ten-year period to 1950 mostly commanded middle wages. However, in the ten-year period to 2018, the new roles that were created were either very high paid or very low paid. In other words, the new technologies were polarising the labour market, creating winners and losers.

Acemoglu and Restropo argue that there are three possible reasons why the relationship between labour and capital is changing. Firstly, recent technological advances have made capital less of a complement and more of a substitute to labour. Platform economics and zero-marginal-cost business models raise the productivity of capital but not that of labour. Second, the tax code incentivises businesses to invest in capital at the expense of labour. Taxes on capital are between 5%-10% while those on labour are between 20%-25%. Policies like the ‘super deduction’ in the UK where businesses can deduct up to 130% of capital expenditure are prime examples of tax disincentives for businesses to hire labour. Lastly, the declining role of public investment in the economy over the last three decades could be hindering labour market flexibility. Public investments – in education, health and infrastructure – typically have very long payoff periods and are critical to helping labour markets dynamically adjust. The absence of such investments could be an important factor in the more muted redeployment of displaced labour over the past two decades.

The pandemic de-leveller

While COVID -19 has upended the way we live and work, it has worsened the inequality in society. Lockdown measures have widened the income disparity between the skilled worker (those with the ability to work from home) and the unskilled worker (many furloughed). Moreover, aggressive liquidity support has raised the wealth of asset owners, widening the chasm between those that derive income from capital versus labour.

There is a growing imperative to reduce inequality and voters are demanding a level playing field for those left behind. The rough contours of a policy shift are starting to emerge. These include an emphasis on pre-distribution policies: those that aim to address the root causes of inequality rather than fixing it with benefits once they have occurred. Signature policies include raising minimum wages, universal basic income and increasing government investment in infrastructure, education, health and technology to improve the outcomes for those less well off. Removing tax distortions that give an unfair advantage to capital, while not currently on the table, are likely to become important over the medium term.

To level up, we will need more financial repression

While modest increases in taxes on corporate income and more progressive income taxes will help fund a more muscular government, there is a growing consensus that a significant part of the levelling up agenda will need to be funded by greater borrowing. With debt levels exceeding 100% of GDP in many developed economies, how will governments manage to do so sustainably?

We expect that central banks will accommodate greater government borrowing by adopting more aggressive policies of financial repression. In the US, the Federal Reserve has pivoted to a Flexible Average Inflation Targeting (FAIT) approach which suggests that it will keep interest rates ultra-low even as inflation moves moderately higher. In Europe, the ECB is currently conducting a Strategy Review, the outcome of which is also likely to signal a commitment to keep interest rates negative to zero for years ahead.

Moderately higher inflation in an environment of near-zero interest rates will create a sustained period of negative real interest rates. Such an environment will help governments expand the public purse to invest in the provision of health, education and infrastructure that can help rebalance the economy.

With inequality so deeply entrenched, levelling up has become a political imperative and alongside it, financial repression is here to stay. Prepare for a world where moderately higher inflation and ultra-low interest rates start to become the norm.