COVID-19 has brought the world to a standstill and disrupted our work and home lives. Our best guess is that these disruptions will continue at least until the summer of 2021. What kind of economy will emerge in its wake? What will the ensuing landscape look like?

Deep recessions meaningfully change economic outcomes. The global financial crisis (GFC) left long-lasting scars, in terms of its impact both on behaviour and on wallets. The world that emerged from the crisis was indebted and impaired, resulting in slower productivity growth, weaker investment and lower labour share of income. To strengthen the anaemic recovery, central banks across the world embarked upon financial repression – an umbrella term which captures a broad range of policies such as the aggressive suppression of interest rates, increased regulation of banks and ringfencing of capital markets. Financial repression was successful in boosting asset prices and corporate profits while supporting growth to a more limited extent. Rising asset prices, in turn, accentuated the prevailing inequity in wealth and incomes. In the last few years, voters across the world have moved to overwhelmingly reject the globally interconnected political status quo in favour of inward-facing policies aiming to ‘level up’ those who have fared less well in the post-crisis world.

The scale and duration of the COVID-19 disruption will likely accelerate many of the long-term trends already underway – financial repression, walled gardens and levelling up – while bringing forward new ones. Here are four features we can expect to see in the post-COVID world.

1. A step-down in growth

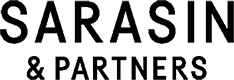

Deep recessions impair balance sheets and lower growth potential. Since 1990, the US economy has emerged from every recession to grow at an incrementally slower pace. Chart 1 below plots the average growth rate for the US economy across recent business cycles.

Source: Macrobond

2. Consumption and investment will not return to normal

We assume that COVID-19 will impact the normal functioning of the global economy for the next 18 months. This is a lengthy disruption that will reshape consumption and investment.

Firstly, lost consumption in the first half of 2020 will not be recouped in subsequent quarters. As lockdown eases, there will be some pent-up demand, but lingering health concerns will significantly reduce this impulse. The rebound in Q3 and Q4 will primarily be driven by a resumption in activity and not by catch-up demand. Households will maintain high levels of precautionary savings and this will suppress consumption growth in 2021.

Meanwhile, business investment will remain weak as uncertainty prevails. Retail, hospitality and leisure sectors are likely to suffer material impairments to their business models and will need to adapt to provide low-contact environments. In contrast, investment in technology, telecommunications, logistics and health systems will likely receive a boost.

Projections suggest that it will take three years for the US economy to recover the output lost as a result of the disruption. Similar projections for the UK suggest that it will take four years for the economy to once again attain 2019 levels.

3. A move from financial repression to fiscal dominance

In advanced economies, government schemes to support income and lending are expected to increase debt-to-GDP ratios by roughly 20% -30%, exceeding conventional thresholds of 100% of GDP in most cases. The key issue for the medium term is if and how this debt will be repaid and the impact of those strategies on growth. We expect that orthodox measures that reduce debt burdens, such as running primary budget surpluses and privatising government assets will be rejected. Instead, heterodox measures – measures previously deemed heretical – will be embraced. Specifically, we not only anticipate greater co-ordination between monetary policy and fiscal policy but we also expect the lines between monetary policy and government debt management to become increasingly blurred.

If the GFC forced the world’s central bankers to adopt financial repression, the ‘no-fault’ COVID-19 recession is likely to push them deeper into repression’s embrace and closer to the world of fiscal dominance. The key pillars are likely to be interest rate repression, banking sector regulation and re-domestication of savings.

4. Walled gardens and a sustained retreat from globalisation

In the post-GFC era, slow growth and widening inequality have propelled many populist governments into power. Leaders have been elected with a mandate ‘level up’ the ‘squeezed middle’ – those in the bottom 90% of the income distribution whose real incomes have been stagnant over the past decade. The populists’ response has been to retreat from globalisation’s upward march and turn economies into walled gardens.

This trend will accelerate in the post-COVID world, which is likely to drive demand to build resilience into supply chains and develop greater independence in critical industries. Additionally, US/China conflict is gaining momentum. The contours of this metaphoric walled garden will include the following:

Trade wall

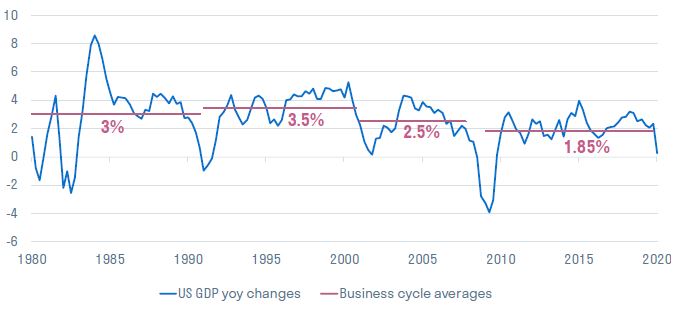

Growth in global trade has been slowing since the GFC. Over the last two years, President Trump’s tariffs on the US’s trading partners have accelerated this downtrend. Chart 2 shows the slowdown in the pace of growth in global trade in the period 2010 -2019 when compared to the period 1992 -2008.

Source: Macrobond

COVID-19-related disruptions are likely to cause a further deceleration in trade as multinationals re-evaluate long, China-centric supply chains. Firms will likely build greater supply chain resilience through geographic diversification of suppliers and increasing local content. Governments are likely to mandate local production in some critical industries, as the US and France already have.

As businesses adjust their supply chains to build resilience, Chinese content in global trade and growth in global trade itself will adjust lower. In time, the growth in global trade is likely to run well below growth in GDP – a dramatic contrast to the trend we have experienced since the early 1990s.

Technology wall

Relations between the US and China have shifted from strategic engagement to strategic rivalry and more recently to strategic hostility. In the US, there is broad bipartisan consensus around the notion that China does not abide by global rules and will likely threaten the liberal order if its economic powers remain unchecked.

Thus far, President Trump has sidestepped post-war multi-lateral institutions where China has a seat at the table. Instead, the Administration has chosen to forge bilateral alliances to curtail China’s growing economic power. In the post-COVID era, the US may abandon its previous unilateral approach in favour of a ‘coalition of the willing’ with a new G11 which could include the US, UK, Canada, Japan, Germany, France, Italy, Australia, South Korea, Russia and India. Trump is keen to intensify US efforts to assert technological supremacy and limit Chinese access.

As the US intensifies its efforts to limit China’s access to critical technologies, China will likely respond by de-Americanising its technology imports. The singular technology ecosystem that we have today will likely bifurcate into two eco-systems that eventually become mutually incompatible.

Immigration wall

Levelling-up policies, which actively seek to reduce the inequality which has increased over the last thirty years, are gaining strength globally. Populist leaders believe that rampant globalisation and migration have exposed lower skilled workers to relentless competition from cheaper labour. They believe that these forces have played a key role in the real wage stagnation of lower skilled workers. Taking back control of borders, therefore, is a crucial first step in raising the living standards of these workers.

In a post-COVID world, immigration is likely to be curtailed, to ensure that jobs that return after COVID are not lost to cheaper migrants. Only with a firm border in place can levelling up policies, aimed those who have done less well after the GFC and those more vulnerable after COVID, be successful.