The Chinese economy navigated the ramifications of the pandemic impressively.

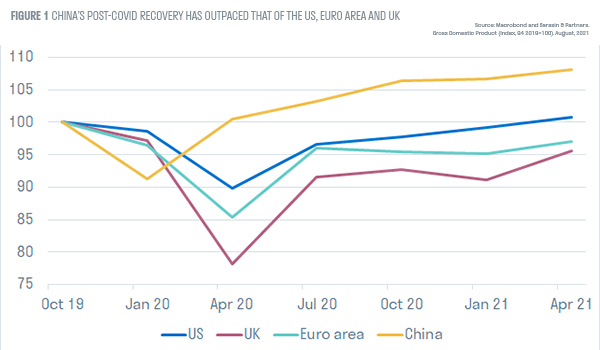

After recording a GDP contraction of 8.7% in Q1 2020, the economy is now not only back to its pre-COVID size but in Q2 2021 was 8.2% larger. In comparison, the US economy has only just regained its pandemic size (Figure 1).

China’s economic outperformance during the pandemic is largely attributed to its initial virus suppression strategy, which although highly disruptive, allowed its economy to re-open faster than most western counterparts, and its export sector to benefit from strong demand for personal protective equipment, electronics and work-from-home goods as the rest of the world grappled with further virus waves.

Risks have risen sharply in the short term

Yet, arguably China is now confronted with even larger risks, both short-term risks – especially within the property market – as well as deep-seated structural challenges which have come closer to the fore. The government’s financial de-leveraging campaign and efforts to tame property price speculation has pushed property developers to the brink. The potential collapse of Evergrande – China’s second largest property developer and the world’s largest indebted property company with liabilities of over $300bn– would invariably affect China’s economy. Deeply intertwined with the broader economy, the property market accounts for as much as one quarter of the Chinese economy, and with high home ownership rates, and as much as 75% of households’ wealth tied to the fate of the property market, a burst of the property market bubble could detract around 1.5% from China’s GDP. The risk is even more acute as consumption has lagged the economic recovery and households remain cautious, with the government’s zero-COVID strategy meaning that mobility restrictions are quickly re-imposed in the face of comparatively small virus outbreaks.

An additional risk stems from the government’s policy of “dual control” to reduce energy consumption and energy intensity as part of the wider decarbonisation agenda. In order to meet end-of-year targets energy-intensive industries, like steel and cement, have limited production, and local governments have rationed energy, resulting in power outages. While this risk is more directly within the government’s control, it is clear that the government is willing to compromise economic activity for longer-term strategic objectives.

Demographic challenges are even closer than thought

Looking further out to the horizon, the publication of the results of the census this year brought China’s demographic challenges into sharp focus. Why this matters is that population growth is one the key drivers of potential economic growth together with productivity growth, both of which are estimated to have declined significantly as the country ages and incomes converge to rich countries. The census showed that China’s population growth has slowed further over the past decade, and birth rates have been lower than anticipated, the corollary being that the population is likely to peak before 2025 – around seven years earlier than current UN medium fertility projections.

In a major policy shift, the government responded: the two-child policy was eased to a “three-child” policy. Social policies are rising higher on the priority list in line with the so-called “Common Prosperity” agenda which aims to narrow the country’s wealth gap. These include pledges to support families with the high cost of childrearing, but much more needs to be done including reducing out-of-pocket healthcare costs, expanding coverage of unemployment insurance and increasing the portability of pension benefits nationally. The OECD, in its “Going for Growth” 2021 publication, notes that the pandemic widened inequalities in China, including between inland vs coastal regions, poorer vs wealthier households, and private corporate vs state-owned enterprises. Reducing these divides will help make growth more inclusive and sustainable. These policy changes are welcome but also need to be carefully managed to ensure a smooth transition.

If you are a private investor, you should not act or rely on this article but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been approved by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England & Wales with registered number OC329859 which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111.

It has been prepared solely for information purposes and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the document is based has been obtained from sources that we believe to be reliable, and in good faith, but we have not independently verified such information and no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

Please note that the prices of shares and the income from them can fall as well as rise and you may not get back the amount originally invested. This can be as a result of market movements and also of variations in the exchange rates between currencies. Past performance is not a guide to future returns and may not be repeated.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the Bank J. Safra Sarasin group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of his or her own judgment. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document. If you are a private investor you should not rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

(c) 2021 Sarasin & Partners LLP - all rights reserved.