The US economy is back on its feet just 15 months after COVID struck. Vast fiscal and monetary stimulus turned the deepest recession on record to the shortest.

While the aftershocks from COVID-19’s economic dislocation are still reverberating across global supply chains and labour markets, there is a growing consensus that as societies adjust to living with the virus, emergency policy support will need to be dialled back.

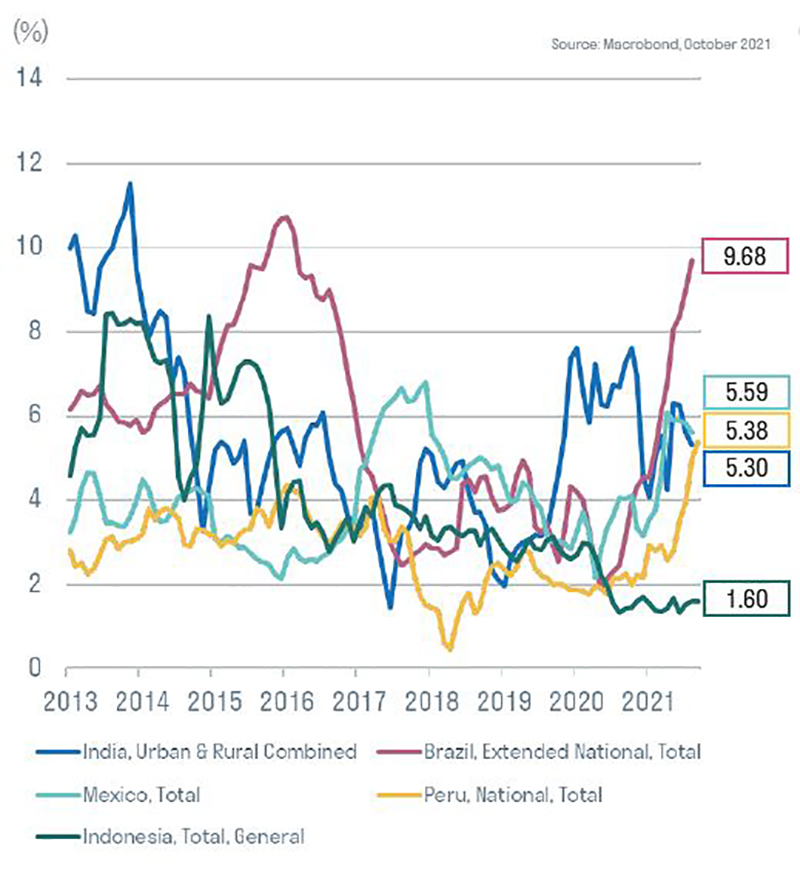

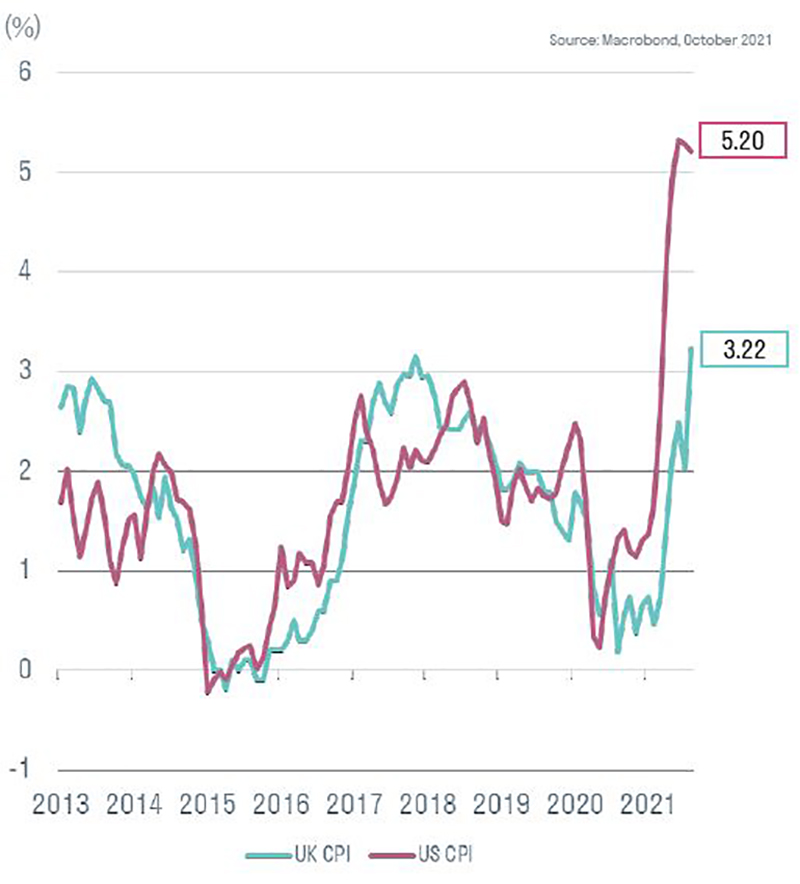

Recalibrating policy for a steady recovery will be a delicate balancing act. During periods of deep uncertainty, monetary support can help underpin consumer, business and market confidence. However, it is not particularly helpful when addressing long-lasting supply-side dislocations. For much of 2021, inflation in the US, UK, Germany and many emerging markets has been running substantially above central bank targets – driven in large part by misalignments between supply and demand. Persistent supply disruptions suggest that inflation will likely remain elevated for much of 2022 as well. If crisis level monetary support remains in place as supply shocks ripple through the economy, well-anchored inflation expectations risk becoming unsettled. To complicate matters, an ambitious fiscal policy agenda that seeks to address climate change and ‘level up’ those ‘who have been left behind’ are likely to add to supply challenges over the medium term.

In the coming months, policymakers will need to perform a high-wire act. They will need to remove crisis-era policies while also ensuring that there is sufficient support to sustain consumer confidence and the recovery in demand. They will need to ensure that inflation expectations remain well anchored even as ‘levelling up’ policies push up the wages of less skilled workers and an active climate agenda puts sustained pressure on supply chains to shorten and decarbonise.

Here are five key issues that investors will need to contend with in the post-pandemic landscape.

- Inflation will be sticky: COVID-19-induced lockdowns have exposed the fragility of long, globalised and interlinked supply chains that run on ‘just-in-time’ inventories. COVID-19 not only threw markets off kilter, but also created supply disruptions that are still rippling through seemingly unconnected markets: semi-conductors, lumber, ships, cars, energy, food. While sharp price spikes are essential to bring supply and demand back into balance, overlapping and interlinked markets raise the risk that these spikes persist for much longer and can change the price-setting behaviour of firms well into the future.

- A “growth at any cost fiscal agenda”: There is now a strong belief that the weak economic recovery that followed the financial crisis was in large part driven by premature fiscal prudence in the post-crisis era. Austerity drives shackled government spending even as households and firms struggled under the weight of a high debt level. The result was a long period of secular stagnation, where monetary policy was pushed to become more and more activist in an effort to offset the disinflationary pressures that arose from the weak recovery. COVID-19, by contrast, is seen to be a no-fault recession where the risks of not doing enough certainly outweigh the risks of doing too much. Politicians are determined to generate a recovery with sufficient momentum to break away from secular stagnation. They have largely abandoned the fiscal rulebook to ensure that the post-pandemic economy generates a rising tide that lifts all boats.

- Levelling up is here to stay: There is broad acceptance within many rich nations that over the past two decades the disparity in wealth and incomes has not only become more widespread but has also reduced economic and social mobility and lowered productivity. In recent years, nations on both sides of the Atlantic have elected politicians to explicitly level up those whose living standards have fallen behind. Levelling up is distinctly different from the redistribution policies of the 1970s. It is a promise to lift up those at the bottom end of the socio-economic distribution without materially impacting those at the top through tax increases. The policy design draws heavily upon deficit-financed social spending to deliver on the objective of raising lower skilled wages. Successful levelling up will ultimately lead to greater government spending, larger deficits and higher wages for the less skilled.

- The climate agenda is set to take centre stage: Next month, delegates from all over the world will be gathering in Glasgow for COP26 where they will discuss their updated plans for the transition to net zero by the middle of the century. Rich countries are likely to come under significant pressure to not only make good on previous capital commitments (transfers of 100 billion US dollars a year to developing economies) but also to make more meaningful domestic investments. To decarbonise the world economy, capital will need to be allocated to newer technologies even as some of the existing capital stock is rendered obsolete. To achieve a net-zero world, we will need to drive down our consumption of carbon, which ultimately means that we will need to appropriately integrate its price into everything we consume. As a result, the transition to net zero will inevitably put upward pressure on prices as they will need to incorporate the price of carbon, either explicitly though a tax, or implicitly through regulation. What is also clear is that in the absence of a comprehensive global framework for the pricing of carbon, we will likely see ongoing supply adjustments that are likely to face frequent disruptions.

- Inclusive employment suggests a higher tolerance of inflation: In the US, the Federal Reserve recently updated its longer run goals and monetary policy strategy to explicitly incorporate maximum employment as below:The maximum level of employment is a broad-based and inclusive goal that is not directly measurable and changes over time owing largely to nonmonetary factors that affect the structure and dynamics of the labour market. The Committee’s policy decisions must be informed by assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its maximum level of employment, recognising that such assessments are necessarily uncertain and subject to revision.

Given that inclusive employment is not directly measurable, changes over time and is necessarily uncertain, the Federal Reserve appears to have adjusted its inflation/employment trade-off in favour of employment. It has signalled a great willingness to tolerate higher inflation to support breadth of gains in the labour market, adopting what is arguably a quasi-fiscal policy objective. Where the US Federal Reserve leads, other central banks have typically followed. What lies ahead is likely a period where central banks relax their dogged focus on inflation to sustain labour market gains that are much more broad based. This is a policy environment where inflation is likely to remain moderately above target and labour markets are likely to be run hot.

The broad contours of the post-pandemic landscape are becoming increasingly clear. Ongoing COVID-related supply disruptions are likely to collide with a more muscular fiscal agenda aiming to address the climate challenge while also seeking to level up societal disparities. This is an environment where inflation will remain stickier and more persistent. Central banks will need to reduce crisis levels of support for the economy to keep inflation expectations anchored, while also running the economy hot to deliver broad-based employment gains and support a more muscular fiscal agenda. This will be a high-wire act which will require both central banks and the wider public to hold their nerve. The success of this balancing act will be profoundly important to solving many of the world’s entrenched problems.