We are entering a new market regime in which old certainties no longer apply. Understanding the new prevailing forces is essential to planning a long-term investment strategy.

It’s been a roller coaster ride for investors. A steady stream of unprecedented shocks has buffeted economies and markets: the pandemic; Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; and now an Israel-Hamas conflict that threatens to engulf the wider Middle East region. All the while, a cold war between the US and China and extreme weather events have been gaining force.

These shocks and the accompanying volatility are a far cry from the low inflation and low interest rates that followed the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-'09 (GFC). They reflect a meaningful shift in the drivers of market behaviour – typically called a market regime.

What is a market regime?

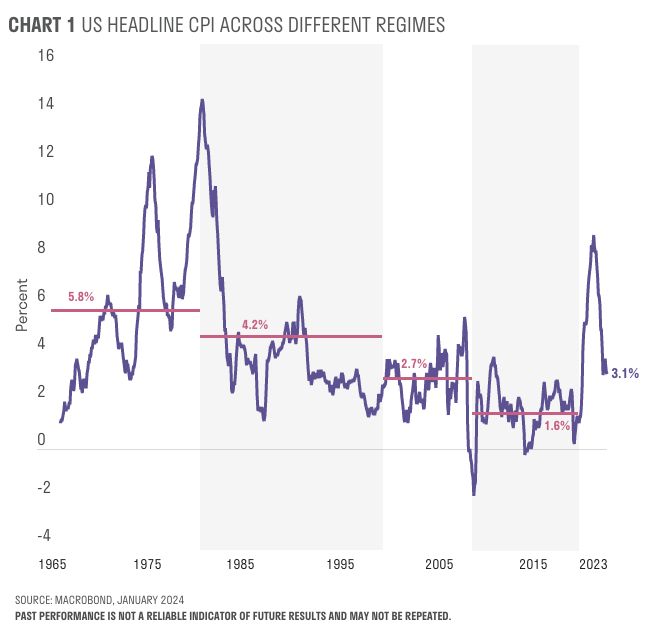

Key investment inputs such as inflation, growth and volatility can trend higher or lower for decades at a time. These persistent trends mean that using long-term historical averages as a predictor of value or guide to future returns might be less useful.

For example, the floating of currencies in the 1970s and the unofficial adoption of inflation targeting by central banks in the 1990s contributed to more stable inflation and higher asset prices. Incorporating this regime shift into investment decisions would have substantially benefited investors. However, regime shifts can sometimes be masked by the volatility of the business cycle, so it is vital to distinguish between the two when planning a long-term investment strategy.

Demographics are changing how we save, spend and invest

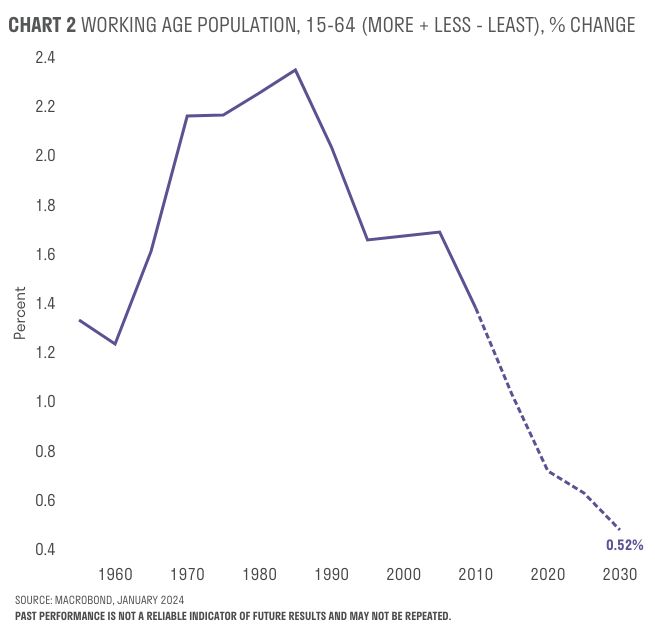

The demographic dividend that advanced economies enjoyed from 1970 to 2010 is starting to reverse. Following World War II, birth rates surged and female participation in the labour force increased dramatically. Around 2015, this demographic windfall began to reverse as populations began to age. The ongoing shift towards older demographics is recalibrating the balance between savings and investments, moving from a world of net savers to net consumers. Ageing populations may also dampen productivity growth as more economic resources are diverted to lower-productivity care sectors. The coming demographic reversal is expected to raise global interest rates.

Technology – AI will boost productivity

The digitalisation of the global economy has been a key driver of productivity. Breakthroughs in generative artificial intelligence (AI) could significantly increase productivity and temper inflation pressures. Over the next decade the technology sector could add meaningfully to productivity growth. Investment strategies should include enablers and beneficiaries of AI and automation.

Government debt could come with a hangover

Over the next decade, fiscal deficits in advanced economies are expected to reach levels rarely seen outside of wartime or recession. In the US, persistent deficits are expected to raise already-high debt levels by around 10 percentage points by 2035. Such fiscal largesse, while stimulating demand in the short run, could reduce long-run growth by 0.2 percentage points annually while raising long-term interest rates by 0.15-0.45%.[1] [2]

Larger deficits are putting upward pressure on short-term interest rates as central banks seek to counteract the inflationary impact of fiscal stimulus. Long-term interest rates have risen, reflecting higher short-term interest rates and higher risk premia. As a result, other productive investment opportunities will suffer.

Unfortunately, the composition of this increased government spending is unlikely to contribute to productivity growth over the next 5-10 years. Defence spending and subsidies for investing in onshoring and renewable energy effectively replace or duplicate the existing capital stock rather than adding to it.

Green transition = investment opportunity

The shift towards a greener economy is gaining momentum, fuelled by regulatory measures and substantial investment. Following the introduction of the Inflation Reduction Act in the US, over $100 billion of clean energy manufacturing investments have been announced.[3] The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report suggests spending globally on the transition needs to increase by between $1-$4 trillion per annum. [4]

This green transition will increase inflationary pressure as prices shift to incentivise reallocation of resources. Productivity is also likely to suffer as investment spending is diverted and existing capital stock becomes obsolete.

A divided world is inflationary

Escalating geopolitical tensions and trade fragmentation are also expected to raise inflation modestly and drag on economic growth. Trade barriers, which initially appear as mere speed bumps, are likely to partially reverse the deflationary effects of integrating China and former Soviet states into the global economy over the past 30 years. Estimates from the IMF suggest that trade barriers could slowly erode annual productivity and economic growth by 0.2 percentage points over 10 years, even as countries successfully circumvent them.[5]

Increasingly fragmented trade and finance may be associated with reduced demand for US dollars and assets. Savings from emerging market economies contributed to the savings glut that put downward pressure on interest rates in advanced economies over the past 20 years. Again, this could potentially contribute to a firming in global interest rates going forward.

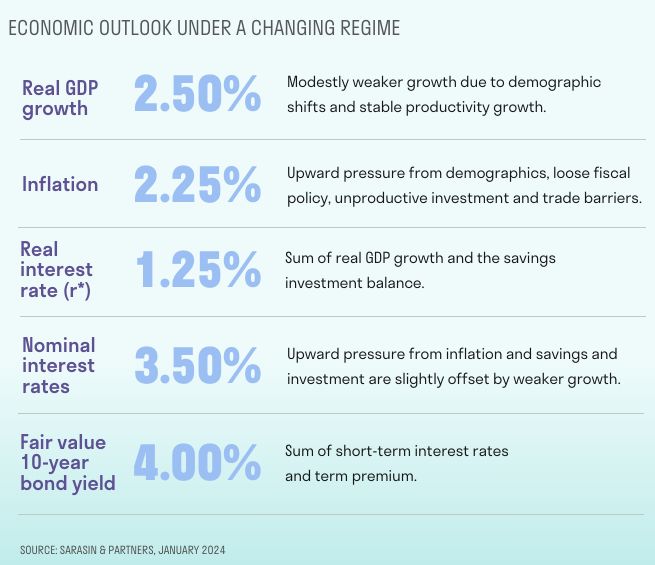

The new economic outlook

As markets adjust to the shift in economic forces, we are beginning to see the rough contours of the new regime. The table here is an illustrative example of how key variables in the US are likely to trend over the next 5-10 years in this regime. These estimates are not precise forecasts, but rough guides to the direction of travel.

Overall, growth will be modestly weaker due to demographic shifts and stable productivity growth. AI presents a wildcard with large potential upside.

Inflation is likely to break from the low levels that characterised the post-GFC era. Central banks are expected to respond with higher interest rates to manage inflationary pressures, marking a departure from the prolonged savings glut era. As a result, US interest rates could average around 3.5% over the next decade – about 1 percentage point higher than in the previous regime.[6]

Central banks are also likely to be less keen on policies like quantitative easing. After recording large losses on previous purchases, they may be less willing to risk taxpayers’ money. Central banks have been price-insensitive buyers of assets and have seemingly underwritten indiscriminate risk taking. Without their support investors should expect greater volatility of asset prices, higher dispersion of returns within asset classes and lower valuations overall. In particular, the bond term premium (the extra yield that investors demand for holding longer-term bonds) is likely to rise from 0% to 0.5% over the next 5-10 years.[7] This should be a fruitful environment for active, well-researched investment strategies.

Higher volatility brings greater opportunities

Investors’ returns will continue to be driven by bearing risk – with equities remaining a main engine of returns. However, with other asset classes such as bonds now offering respectable long-term returns, a more traditional approach to asset allocation is likely to be warranted. Greater expected volatility will significantly increase the benefits of diversification, particularly for multi-asset approaches focused on harvesting risk premia across different asset classes.

Finally, as the world adjusts to the new regime there will be greater dispersion between the winners and losers: it will be more important than ever to identify the shifts in global trends and long-term investment themes.

[1] Source: Sarasin & Partners analysis and The Cato Journal, The Impact of Public Debt on Economic Growth, 2021.

[2] Source: The Aggregate Demand for Treasury Debt, Krishnamurthy and Vissing-Jorgensen, 2007 (working paper)

[3] Source: Climate Action Tracker

[4] Source: IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023

[5] Source: Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism by IMF 2023

[6] Sarasin & Partners, January 2024

[7] Sarasin & Partners, January 2024

Important information

This document is intended for retail investors. You should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been issued by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859, and which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111.

This document has been prepared for marketing and information purposes only and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the material is based has been obtained in good faith, from sources that we believe to be reliable, but we have not independently verified such information and we make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

This document should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

The value of investments and any income derived from them can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. If investing in foreign currencies, the return in the investor’s reference currency may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results and may not be repeated. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of their own judgement. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document.

Where the data in this document comes partially from third-party sources the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information contained in this publication is not guaranteed, and third-party data is provided without any warranties of any kind. Sarasin & Partners LLP shall have no liability in connection with third-party data.

© 2024 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP. Please contact [email protected].