Key points

- UK public spending has climbed significantly in recent years to around 45% of GDP currently.

- Ahead of November’s Autumn Budget, the Government reportedly faces a fiscal hole of around £30bn.

- We believe that productivity reform is sorely missing in Labour’s agenda – the UK must rediscover a healthier appetite for risk and innovation

We believe that Labour’s plans for the UK economy lack vision, ambition and speed. It is fixated on budget arithmetic, but fiscal rules alone, however prudent, only slow the bleeding. Voters want cake: strong welfare, quality public services and lower taxes. To deliver this, the economy needs an urgent reset and the upcoming Budget is an opportunity.

Credit where credit’s due

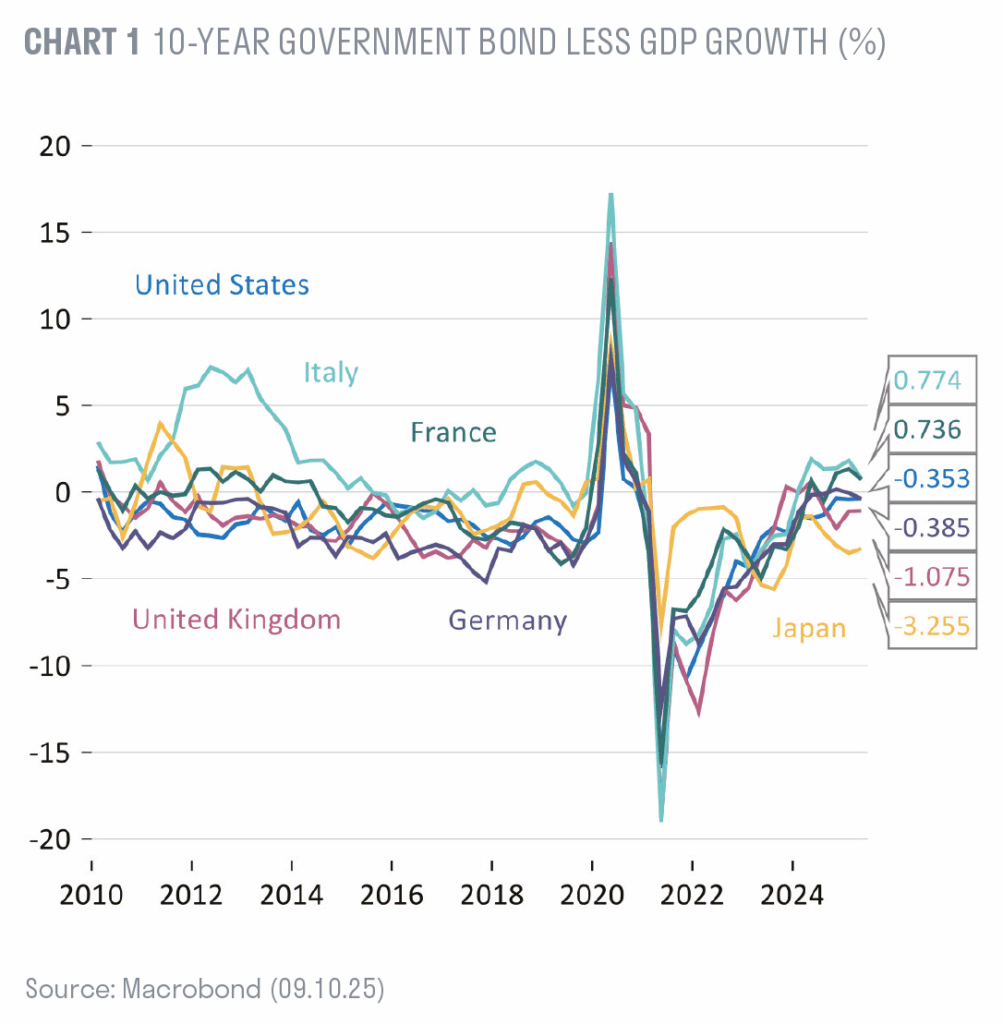

The Government deserves credit for sticking to the fiscal rules. They reassure investors that deficits will be contained. They are part of the reason that UK 10-year borrowing costs adjusted for nominal GDP growth are below that of France, Italy, Germany, and the US (chart 1).[1] Credibility is precious. What upsets most people about the fiscal rules is the reactive tinkering caused by leaving such small margins for safety. However, most previous governments can be criticised for having taken the same action.

To abandon the fiscal rules would be to invite another 2022 debacle, when Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng’s ‘mini-budget’ of aggressive tax cuts led to bond market turmoil.[2] Any short-term stimulus the Government might imagine it can deliver in doing so will be snuffed out by higher interest rates from the Bank of England.

Yet the fiscal rules by themselves tell you little about how government intends to shape the economy, beyond keeping the bond market happy.

In this Budget, the short run is irrelevant

The Government reportedly faces a £30bn fiscal hole in November’s Autumn Budget[3] – roughly the sum of a productivity downgrade and the £5bn welfare rollback. Dare we say it, perhaps the OBR might be a little too harsh at least on the revenue forecast. We say this because while the productivity assumption was probably too optimistic given the current policy mix, the OBR nominal GDP and inflation assumption is too conservative. For example, the OBR forecast for nominal GDP growth over 2025 is around 3.5% whereas to Q2 2025 it is currently growing at 5.5% and has averaged 5% over past two years and around 5.5% since 2020.[4]

The Bank of England has persistently run the economy too hot while talking it down, blaming import prices or foreign supply chains. The political incentive, as in the US and Japan, is to continue doing so. This is part of the reason why we favour gold and equities. Britain’s policy mix persistently delivers inflation which translates to nominal growth. But with a high share of borrowing and spending indexed to inflation – and a bond market unlikely to be fooled twice – a better strategy would be to focus on boosting productivity growth. Plug the fiscal hole, let the Bank of England manage the cycle, and start fixing the structure.

The tax and spend model of the past 25 years is exhausted

Since the early 2000s, the state’s footprint has widened dramatically. Public spending has swollen from roughly one-third of GDP to almost one-half.[5] Ageing demographics, welfare and new defence pledges make it hard to deliver even modest restraint on spending growth. The recent rejection of welfare reforms shows how politically fraught the task has become.

Taxpayers are not getting value for money in many areas, and the groundwork for a serious conversation about what government can and cannot deliver has yet to be laid. Some outright spending cuts are inevitable. Sacred cows like the triple lock pension policy[6] may be simply unaffordable.

The current tax base is too narrow and needs to be broadened. Rates are already near their practical ceiling, given global competition for capital and talent. A more efficient system would lower marginal rates, broaden the base, and shift the burden from income, capital and transactions (like stamp duty) to consumption (VAT) and property. Taxes and spending must be viewed together for their combined distributional impact, not in isolation. We agree with the Government to make work pay. These are bolder debates than any party currently dares to have.

The old recipe of cake for all – more spending, hope for growth, rising debt – is exhausted.

In the long run, productivity is everything

We believe that productivity reform needs to be prioritised. The only sustainable way to lift growth, tame inflation and improve living standards is to shift the supply curve right. Often, this requires the state to do less, not more.

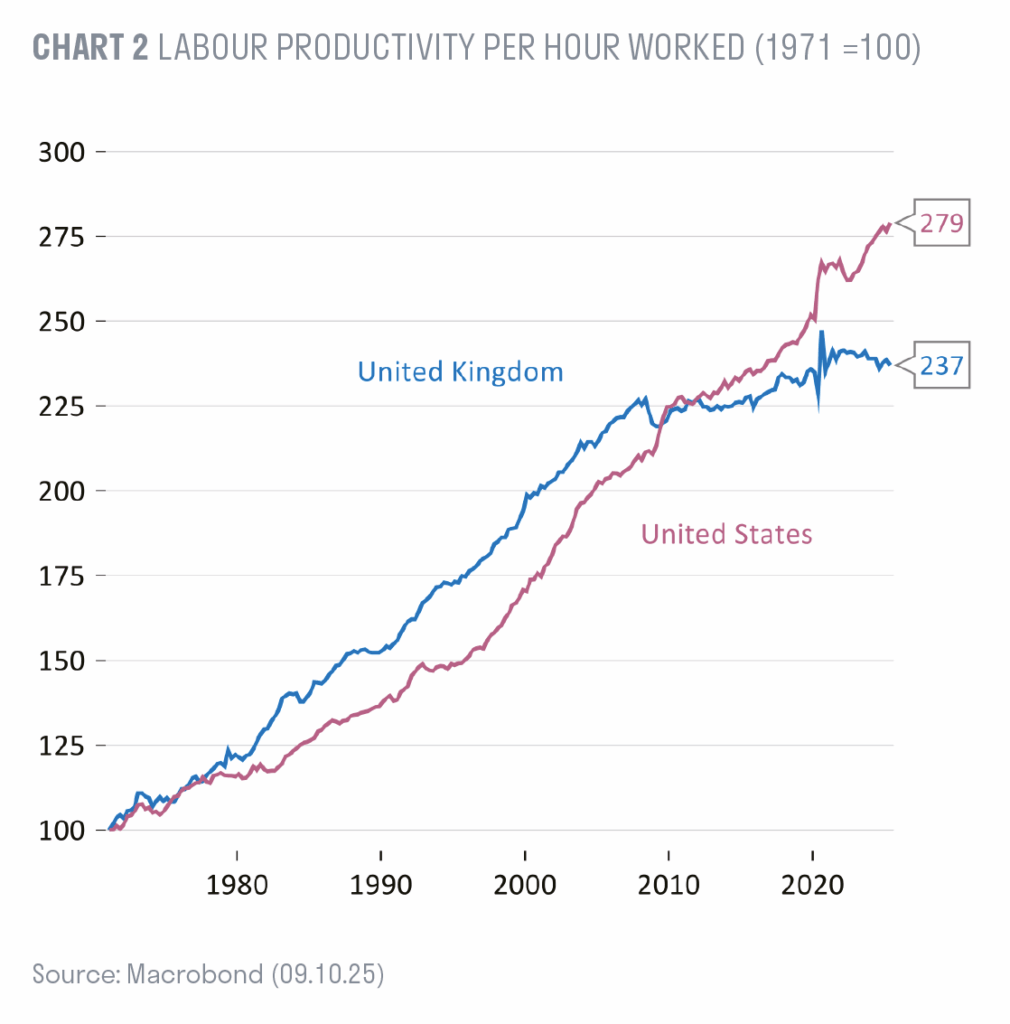

It is not just about pounds and pence spent, but about the rules and regulations that shape behaviour. The financial crisis of 2008–09 bequeathed a culture of overregulation and risk aversion that has spread well beyond the financial sector, where banks at least genuinely required better oversight. Britain has become a country where failure is stigmatised and red tape stifles entrepreneurial dynamism. Productivity has flatlined relative to the US (chart 2).

From red tape to risk-taking

If the goal is to foster growth, the UK must rediscover a healthier appetite for risk. Innovation depends on tolerance for failure. Without it, productivity stagnates, capital flees, and the economy becomes ever more dependent on fiscal transfers rather than private initiative.

Artificial intelligence promises a profound transformation of work. To adapt and thrive, businesses must restructure their workforces and invest in new technologies — a dynamic process that can only occur if they can flexibly adjust the size and skills of their teams.

Regulation should lower, not raise, the barriers to such adaptation. The Employment Rights Bill,[7] now in discussion, risks moving in the wrong direction. Regulators must recalibrate rules to foster, not suppress, responsible risk-taking. Taxes too should be redesigned to encourage investment in new technologies.

AI offers a once-in-a-generation opportunity to lift the economy out of its low-productivity doldrums. Labour’s proposals, in our view, are simply too slow – and too timid – for the scale of the challenge.

The OBR sent this message loud and clear in March: the Government’s housing planning reforms[8] lower borrowing not by austerity but by boosting GDP. Not to mention the higher incomes and more affordable housing costs. Sometimes, less really is more.

Imagine the OBR applying the same analysis of the housing planning reforms to childcare, healthcare, transport and energy. Perhaps we could actually see prices falling like they have for TVs, computers, and cars at least in relative terms.

Unintended consequences and unseen costs

Well-intentioned policy often has unintended consequences. Take the rise in youth unemployment. It is not because young people are lazy – participation is up lately[9] – but because policy has priced them out of work. Minimum wages rose faster than productivity. Hiring is taxed, firing restricted. Employers simply cannot afford to take them on. The irony is stark: having created the problem, government now taxes more to fund job schemes for the same youths it pushed out of the market.

Tidy numbers but a stagnating economy?

Labour’s caution is understandable, and fiscal rules are necessary. But they are not sufficient. Without a vision for the role of the state and a plan for productivity, there is a risk of drifting into a managerial political style that keeps the numbers tidy while the economy stagnates.

Everyone wants cake: strong welfare, quality public services, and lower taxes. Without growth, this becomes a zero-sum game of dividing a shrinking pie. With growth, the UK can sustain both a generous welfare system and fiscal stability. The Government promised it but has not identified the right policies to deliver it.

[1] https://tradingeconomics.com/united-kingdom/ government-bond-yield

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/September_2022_United_ Kingdom_mini-budget

[3] https://www.ft.com/content/efed5b1f-0a3c-4f94- 9d7c-64c57445f4ad

[4] https://obr.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-march-2025/

[5] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/public-spending-statistics-release-may-2025/public-spending-statistics-may-2025

[6] https://www.moneyhelper.org.uk/en/blog/retirement/state-pension-triple-lock

[7] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/employment-rights-bill-factsheets

[8] https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3946

[9] https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn05871/

Important information

This document is intended for retail investors and/or private clients. You should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been issued by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859, and which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111.

This document has been prepared for marketing and information purposes only and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the material is based has been obtained in good faith, from sources that we believe to be reliable, but we have not independently verified such information and we make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

This document should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

The value of investments and any income derived from them can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. If investing in foreign currencies, the return in the investor’s reference currency may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results and may not be repeated. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of their own judgement. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document.

Where the data in this document comes partially from third-party sources the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information contained in this publication is not guaranteed, and third-party data is provided without any warranties of any kind. Sarasin & Partners LLP shall have no liability in connection with third-party data.

© 2025 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP. Please contact [email protected].