There is a palpable feeling of relief across the financial community that the bout of volatility seen in world markets earlier this month was not rather worse.

After more than five years of consistently rising prices and falling volatility across most asset classes, there is a feeling that we may have ‘gotten off lightly.’

Anatomy of the correction

The MSCI World Index (ACWI) peaked on 26th January and troughed on 8th February, representing a total intra-day decline of more than 10% in US dollar terms. It was a correction that had some parallels with a very mild version of 1987 – both moves had no obvious financial triggers or political catalysts but saw a violent move that was largely technical in nature, on the heels of rapid market gains in the prior year. Certainly, the suspicion this time was that funds targeting volatility exacerbated the declines in equities by hedging the rise in the volatility (VIX) index with direct equity sales.

There were also parallels with the bond correction seen in 1994, where both equity and fixed income assets fell in tandem. Indeed, one of the most alarming features of last month was the lack of any safe havens for investors – government and corporate bonds, developed and emerging equities, oil and metals, and many ‘alternatives’ all corrected simultaneously. For a few days at least cash was king – a difficult position for many balanced investors who have been used to retaining only minimal liquidity positions with yields so low (and in Europe’s case negative).

The correction was also unusual because equity leadership was largely counterintuitive. At the headline level, for example, among the most defensive major indices was actually the technology-rich NASDAQ, while among the most vulnerable was the FTSE100 (with its low valuation, high running yield and large weightings in the supposedly defensive pharmaceutical and oil sectors). For example in 2018 to date Royal Dutch Shell (with a yield of over 6%) is still showing a decline of 7%, while Amazon (with a forward price-to-earnings multiple of 175) has gained almost 20%, even adjusting for a weaker dollar. While Brexit-related flows no doubt exaggerated UK declines, the general feeling was that classically defensive or value sectors offered little – if any – additional protection.

Good news for economic growth can also be bad news for markets

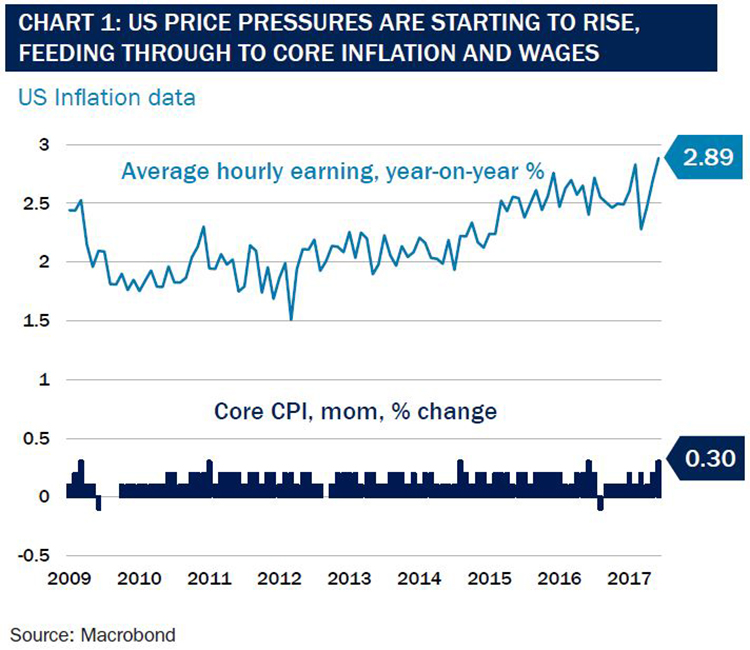

After nearly a decade where improving economic growth has generally led to rising financial markets, we are now at a point in the cycle where a further acceleration in growth risks a meaningful response from central bankers. For some months now, the US has seen surprisingly strong wage and inflation data with annual growth in average hourly earnings currently running at 2.9%, the strongest pace since the recession (see Chart 1). These price pressures are starting to be felt even in the core consumer price index (CPI), which rose robustly in January with broad-based increases recorded across most price categories.

This late stage pickup in US growth has been amplified not just by stronger global growth and a weaker dollar, but also by the US government’s $1.5 trillion tax cut for corporates and individuals – together these are likely to boost GDP growth to around 2.75% in 2018. While the White House argues that stronger growth means higher tax revenues, most commentators see the president’s latest $4.4 trillion budget proposal (including $200 billion of federal spending to improve infrastructure) as jeopardising fiscal sustainability. Estimates suggest that the budget deal will increase next year’s budget deficit to around $1.2 trillion, and cause debt to rise from around 76% of GDP today to over 90% by 2027.

Unsurprisingly, the bond market is concerned both that the White House is adding fuel to a US economy that is already running hot. There may also be some additional worries that this critical phase of Federal Reserve policy will be overseen by the new Chair, Jay Powell. It may be simply co-incidence, but both bonds and the dollar were markedly weaker in the weeks immediately following the announcement of his appointment on 2nd November 2017.

In short, we are entering a new era where managing economic growth, rather than generating an economic recovery, is now at the heart of central bank policy. This implies more rapid policy tightening (four rate rises are now likely in the US this year) alongside an accelerated winding down of quantitative easing in Europe. Even in the UK, despite Brexit risks, interest rates will likely rise to 0.75% in May. Against this backdrop, then, expect a continued upward trend in bond yields, higher asset price volatility and the end of the expansion in equity valuations that has underpinned so much of the bull market.

What does this mean for investors?

We talked at the end of last year about making portfolios more robust, in preparedness for year of likely ebbing monetary policy support for global asset prices. We took four key policy steps to effect this: lifting cash weightings, introducing portfolio insurance by buying equity index puts (where permitted), adding to US bank equity positions as a hedge against rising yields, and beginning a programme of profit-taking in higher beta and more highly-valued equity positions. The first three measures were all helpful through the market correction, and we were broadly pleased by the low portfolio volatility we achieved. Interestingly though, we probably underestimated the support that the US tax changes would give to technology and growth stocks in terms of future equity buybacks or special dividends.

In recent days we have of course seen an impressive rebound in global equity markets which has been supported by the fact that although government bond yields have continued to rise, the pace is far more modest. Our suspicion, though, is that February’s mini shock is an indicator of deeper changes in liquidity which ultimately threaten today’s high equity valuations and low bond yields. We will continue, therefore, with our programme of strengthening portfolio resilience, running higher precautionary cash balances and retaining our portfolio insurance. We have just witnessed a very manageable market tremor, but it is unlikely to be the last.