Key points

- We are seeing renewed attempts to loosen post-financial crisis era banking sector regulation, particularly within the US. However, despite the rhetoric, capital requirements are likely to rise due to Basel 3 but they could be offset by reduced systemic surcharges.

- While regulatory frameworks are being simplified and adjusted, this does not amount to widespread deregulation and any changes are unlikely to materially boost bank lending.

- Post-Covid, higher interest rates and benign credit quality in banks’ loan portfolios have supported record or near-record profitability across much of the sector.

Financials, and in particular the banking sector, remain a significant part of our investment universe. We invest in the sector as part of our overarching Security theme, especially considering banks’ limited exposure to geopolitical disruption.[1] Here we focus on a loosening regulatory environment, with perspectives from our analysts across both equities and fixed income markets.

Eoin Mullany, Analyst, Global Equities

Since Donald Trump returned to the US presidency, there has been renewed political momentum to reduce regulation, particularly in banking. The Federal Reserve’s new Vice Chair for Supervision, Michelle Bowman, has emphasised the need for a regulatory framework that allows banks of all sizes to operate efficiently and support economic growth.[2]

In practice, proposed changes focus on simplifying rules rather than materially lowering capital requirements. One area attracting attention is the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR), which limits how much banks can expand their balance sheets relative to capital. While some argue that relaxing the SLR would allow banks to buy more US Treasuries, the more important aim is to ensure that banks can continue to intermediate Treasury markets during periods of stress, when balance sheets naturally expand.

Despite the deregulatory rhetoric, capital requirements for large US banks may still rise. Recent media reports suggest the Federal Reserve is considering a 3–7% increase in total capital requirements, only slightly below earlier proposals.[3] However, this increase could be offset by reduced systemic surcharges. Our own recent discussions with US regional banks suggest these changes are unlikely to have a meaningful impact on profitability.

Outside the US, the direction of travel differs by region. In the UK, regulators have modestly reduced banks’ capital requirements following improvements in risk measurement and a reassessment of systemic risks.[4] While this lowers the capital buffer banks must hold, it does not

represent a significant easing of financial safeguards.

In the eurozone, the European Central Bank is not seeking deregulation. Instead, it wants to simplify the framework by reducing complexity and

duplication in reporting.[5] Proposed changes would reorganise capital buffers into clearer categories, without reducing the overall amount of capital banks are required to hold.

Switzerland stands apart. Following UBS’s acquisition of Credit Suisse, regulators initially proposed a large increase in capital requirements for UBS. More recent signals suggest a softer stance, potentially reflecting concerns about UBS’s global competitiveness.

A common argument for lowering capital requirements is that it would encourage banks to lend more. While banks do tend to lend less when capital requirements rise, the evidence that lower requirements lead to sustained increases in lending is mixed. During the pandemic, lending increased materially and evidence from the ECB shows that loans volumes were proportionally stronger in countries with a higher take-up of government guaranteed loans implying that government guarantees rather than lower capital requirements drove stronger lending volumes.[6]

Today, most banks hold capital well above regulatory minimums and management targets. In our view, the constraint on lending is demand rather than supply. As a result, any reduction in capital requirements is more likely to lead to higher shareholder distributions than a meaningful increase in lending.

The bottom line is that while regulatory frameworks are being simplified and adjusted, this does not amount to widespread deregulation. Capital levels remain high, and changes are unlikely to materially boost bank lending.

Artemis Vrahimis, Portfolio Manager/Analyst, Fixed Income

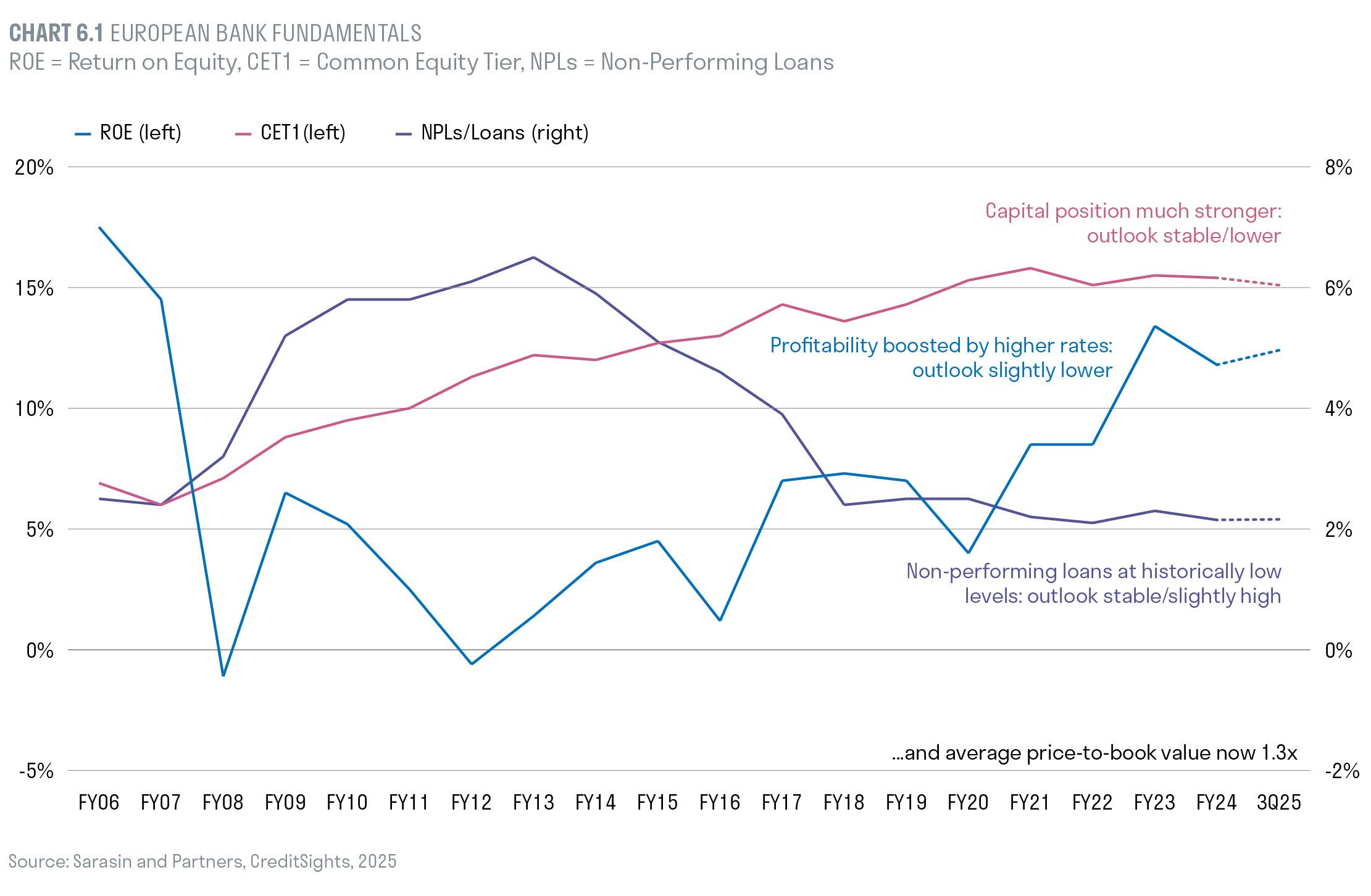

In the years since the global financial crisis in 2008, the increasingly tight regulatory environment that followed has been highly supportive of banks’ credit profiles. This has enabled banks to strengthen their balance sheets through a prolonged period of de-risking and restructuring, leading to significantly stronger capital, liquidity and asset quality. These improvements supported credit for years to come, providing confidence for investors to explore opportunities lower in the capital structure, given the comfortable buffers above regulatory minimum requirements.

Post-Covid, higher interest rates and benign credit quality in banks’ loan portfolios have supported record or near-record profitability across much of the sector.[7] Building on this strength, many institutions have generated significant amounts of capital while gradually increasing distributions to shareholders through higher dividends and buybacks [8] – all from a position of already strong capitalisation.

Loosening banking regulation has become a key theme for the US, UK and European sectors. Whether driven by concerns around competitiveness, the desire to simplify complex regulation, encourage higher lending, or by more politically motivated aims such as facilitating greater Treasury intermediation, elements of deregulation are emerging. While this has been mostly led by changes in the US, the UK appears to be following suit, albeit in a more conservative and incremental manner, while in Europe, policymakers’ ‘simplification over deregulation’ stance appears more cautious. For bond investors, the key question is what these changes mean for bank fundamentals – and whether they risk undermining the fixed income market’s long-standing confidence in the sector.

this has been mostly led by changes in the US, the UK appears to be following suit, albeit in a more conservative and incremental manner, while in Europe, policymakers’ ‘simplification over deregulation’ stance appears more cautious. For bond investors, the key question is what these changes mean for bank fundamentals – and whether they risk undermining the fixed income market’s long-standing confidence in the sector.

In the US and the UK, the most significant changes relate to capital requirements. In the US, looser leverage constraints for global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) – those whose size, complexity and interconnectedness mean their failure could seriously disrupt the global financial system – give the largest banks greater flexibility to expand balance sheets in lower-risk activities without the SLR acting as the binding constraint. [9] A clear example is intermediation in the US Treasury market, which policymakers explicitly intend to encourage.[10] In addition, a lower leverage requirement feeds through into total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) – measures ensuring systemically important banks can absorb losses and be recapitalised without taxpayer support – resulting in meaningful reductions in funding needs.

In the UK, the Financial Policy Committee has lowered its benchmark system-wide Tier 1 requirement from 14% to 13% of risk-weighted assets – equivalent to a common equity tier 1 (CET1) capital ratio of around 11% – and has opened the door to further fine-tuning of capital and leverage requirements.[11]

While the capital released from these regulatory changes is not significant, lower requirements can, in theory, be credit-negative if they lead to riskier lending or higher shareholder distributions. This could result in asset quality deterioration and/or a reduced ability to absorb unexpected losses in a downturn. Indeed, in the US we believe it is unlikely that banks will fully deploy the additional balance sheet capacity generated by the rule change into 0%-risk-weighted assets such as Treasuries. For policymakers, however, the adjustment preserves the sector’s ability to step in to the Treasury market at times of heightened activity or stress.

In Europe, regulators appear to be taking a more cautious approach, avoiding outright reductions in capital requirements.[12] That said, certain proposals may lower operational costs by simplifying reporting obligations. However, the reforms also raise important questions about the future of Additional Tier 1 (AT1) instruments. If reforms make AT1s more equity-like – or phase them out in favour of CET1 over time – banks’ funding costs could rise, potentially altering the relative attractiveness of different parts of the capital structure.

Within our fixed income portfolios and credit sleeves, we remain overweight banks in risk terms. Although deregulation introduces potential downside risks, we believe these are mitigated by the strong governance, conservative underwriting standards and robust capital buffers of the institutions we hold. On this basis, we intend to maintain our overweight positioning and would look to add selectively to our highest-conviction names if market volatility creates opportunities at more attractive spreads.

[1] https://sarasinandpartners.com/think/security-a-new-themeshaping-

our-investment-approach/

[2] https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/files/

bowman20250205a.pdf

[3] https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/

us-fed-floats-plan-with-far-smaller-capital-hikes-big-banksbloomberg-

news-2025-10-22/?utm

[4] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/financialstability-

report/2025/financial-stability-report-december-2025.pdf

[5] https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2025/html/ecb.

sp251211~3336189bc9.en.pdf

[6] https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/economic-bulletin/focus/2020/

html/ecb.ebbox202006_07~5a3b3d1f8f.en.html

[7] https://www.fnlondon.com/articles/investment-banks-scoop-

103bn-in-second-best-year-on-record-801a2279

[8] https://www.ft.com/content/597eb4dc-4002-4c36-

95d3-8a7579e6745

[9] https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/boardmeetings/files/

leverage-ratio-memo-20250625.pdf

[10] https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/IF/PDF/

IF13078/IF13078.1.pdf

[11] https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/financial-policy-committeerecord/

2025/december-2025

[12] https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/

ecb-proposes-simpler-bank-capital-rules-2025-12-11/

Important information

This document is intended for retail investors and/or private clients. You should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been issued by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859, and which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111.

This document has been prepared for marketing and information purposes only and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the material is based has been obtained in good faith, from sources that we believe to be reliable, but we have not independently verified such information and we make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

This document should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

The value of investments and any income derived from them can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. If investing in foreign currencies, the return in the investor’s reference currency may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results and may not be repeated. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of their own judgement. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document.

Where the data in this document comes partially from third-party sources the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information contained in this publication is not guaranteed, and third-party data is provided without any warranties of any kind. Sarasin & Partners LLP shall have no liability in connection with third-party data.

© 2026 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP. Please contact [email protected].