Key points

- AI hype is not a modern phenomenon: but only now is it truly fulfilling its potential.

- AI technology is no longer an experiment layered on top of the economy; it is becoming part of how the economy operates.

- However, patience is required as the technologies that matter most economically rarely deliver immediate gratification.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is often discussed as a breakthrough moment – a sudden leap in capability that promises rapid transformation. History suggests a different framing is more useful. The most important technologies are not those that deliver instant productivity gains, but those that quietly reshape investment, organisation, and behaviour over time. Electricity, computing, and the internet followed this path. AI appears to be doing the same.

Understanding AI as a general-purpose technology helps explain why its economic impact is likely to be substantial, gradual, and uneven – and why the near-term effects are showing up first in investment and demand rather than in headline productivity statistics.

From AI cycles to an economic ecosystem

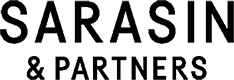

Rather than just a modern phenomenon, AI hype spans the decades through what we see as three clear eras. Earlier AI waves ultimately disappointed because they lacked the economic and technological complements required for scale. The first AI wave from the 1950s to the 1970s relied on hand-coded rules and had no learning mechanism – being dependent upon human input was a huge limitation, compared to today’s programmes that are more autonomous and can scale. The ‘Expert Systems’ of the second AI wave in the 1980s captured narrow expertise but were brittle, expensive, and difficult to maintain. In both cases, deployment was bespoke, local, and commercially fragile.

Today’s deep learning and generative AI is fundamentally different. Modern systems learn directly from data, improve continuously, and are deployed globally through cloud infrastructure. Foundation models generalise across tasks – language, code, vision, and reasoning – and can be embedded directly into production processes. This shift from isolated software to scalable economic input is what distinguishes the current cycle.

Crucially, the surrounding ecosystem now exists: abundant data, specialised computing power, global cloud networks, and digitally mature firms. AI is no longer an experiment layered on top of the economy; it is becoming part of how the economy operates.

AI in historical perspective: Why productivity takes time

History offers a consistent lesson. General-purpose technologies require heavy upfront investment and organisational change before their benefits appear in terms of productivity. Electrification raised costs for years before factories were redesigned around electric motors. Information technology boosted investment in the 1990s, while its productivity impact became clearer only later.

AI fits this pattern. Early phases are characterised by experimentation, duplication, and learning. Firms invest before they fully understand where returns will come from. Productivity gains are real, but they are back-loaded – emerging only once workflows, skills, and capital structures adapt.

This helps explain why AI can be economically important even if near-term productivity statistics appear underwhelming. The early macro story is not efficiency; it is capital formation and diffusion.

How AI diffuses through the economy

AI does not transform entire industries all at once. Instead, it improves specific tasks within jobs. Evidence suggests that in tasks where AI can be used – such as coding, research, customer service, and professional writing – productivity gains, measured by time saved, are around 30% on average.[1]

To understand what this means for the whole economy, researchers start at the task level and work upward. First, they look at how much of each sector’s work is exposed to AI. In sectors like IT and finance, roughly 70% of tasks could benefit from AI, while in sectors such as agriculture, the share is closer to 20%.[2]

Second, they account for the fact that adoption takes time. Firms need to reorganise workflows, invest in systems, and retrain workers. Based on past experience with technologies like computers and the internet, a reasonable assumption is that around half of these AI-exposed tasks are adopted over the next decade.

Putting this together implies a meaningful but gradual increase in productivity. For the US, these assumptions point to roughly one percentage point of extra labour productivity growth per year over the next ten years, similar to the boost seen during the 1990s technology boom. Over time, that compounding effect could leave the US economy more than 10% larger than it would otherwise be.

Other countries are likely to see smaller gains, reflecting differences in economic structure and adoption speed. The key takeaway is not the exact number, but the direction: AI’s productivity impact is real, material, and takes time to unfold.

Building the AI economy though investment

Before productivity shows up, AI’s first major economic effect comes through investment. Data centres, power infrastructure, and supporting networks require large, sustained capital spending.

As Chart 4.2 shows, current estimates suggest that global data-centre investment could reach around $5trn between 2025 and 2030, with roughly $2–3trn in the US. Annual US AI-related investment is projected to rise from roughly $150bn mid-decade to around $400–450bn by 2030. After accounting for imported components and a positive multiplier to other sectors, this translates into a direct boost to US GDP growth of around 0.2–0.3 percentage points per year, with upside if hardware needs to be replaced more frequently or if complementary infrastructure investment accelerates.

Others have speculated that we could see much higher contributions to US growth for a variety of reasons. These include failing to account for imports, using real GDP contributions, which is unreliable because of the volatile price of investment over time, and focusing on the first two quarters of 2025 only (Chart 4.2).

This investment cycle is not occurring in isolation. It is supported by a rare alignment of forces that have been common to previous investment booms:

- Technological necessity: AI is capital-intensive by design, pulling forward investment in computing, energy, and networks.

- Strategic competition: Geopolitical rivalry and defence considerations create demand certainty for advanced computing and semiconductors.

- Policy support: Industrial policy, tax incentives, and public procurement reduce risk and anchor long-term projects.

- Financial conditions: A policy environment that favours production over consumption lowers effective hurdle rates for investment.

Together, these forces help explain why the AI investment boom looks durable, especially as it diffuses beyond data centres.

Future productivity, wealth effects, and today’s household spending

Investment is not the only channel through which AI affects the economy. Expectations about future productivity and income may also be reflected in household behaviour today.

When households perceive stronger future income prospects, those expectations are capitalised into asset values. However, note that not all participants in an economy stand to benefit. For example, advances in AI can create uncertainty about the future income prospects for those on the first rung of the career ladder, with employers preferring to use AI rather than hire inexperienced workers.

However, in aggregate we believe that AI should have a positive impact on our wealth overall. Higher wealth reduces precautionary saving and allows spending to grow faster than current income for a period. In this way, wealth effects act as a bridge between future productivity and present-day demand.

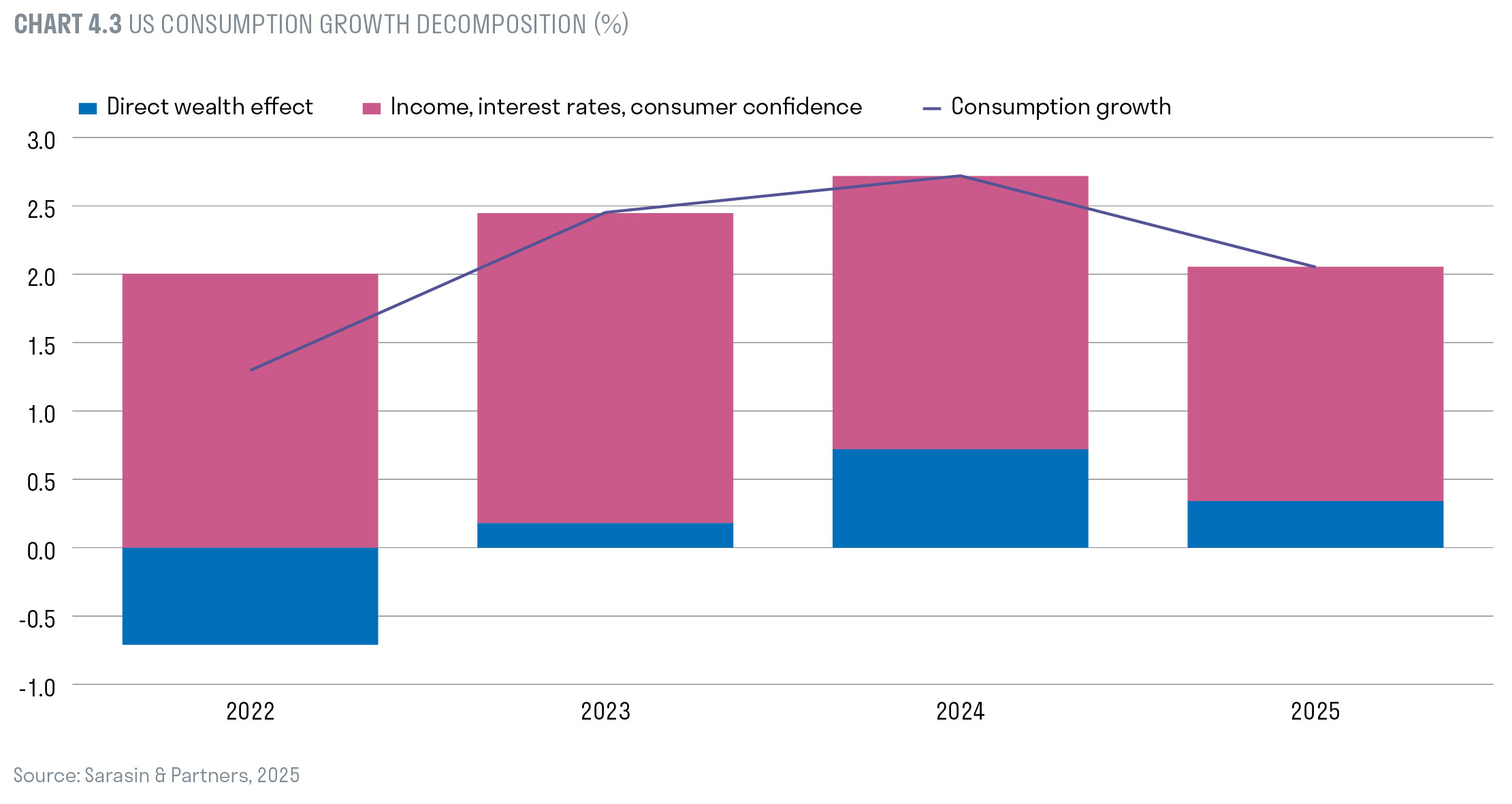

Our own regression model (Chart 4.3) estimates suggest that higher household wealth, including the roughly 20% inflation-adjusted increase in US stocks in 2024, boosted US consumption growth by around 0.8 percentage points to around 2.75%, including indirect effects. In 2025, assuming more modest gains, the wealth contribution is expected to have eased to around 0.5 percentage points.

This perspective helps explain part of the reason why US consumption has remained resilient despite tariffs and broader policy uncertainty. Households appear to be partially internalising future income gains today, with AI-related optimism playing a supporting role.

Combining our investment and consumption contributions, we estimate that AI accounted for a little under half of US growth in 2025 when all is said and done. Contrary to the claims by some commentators, the US economy would not be in recession without it. The US economy is a huge diversified economy with many drivers.

Adjustment costs and constraints

None of this implies a frictionless transition. Investment booms come with adjustment costs. Labour markets must reallocate tasks and skills. Energy and construction constraints can raise prices in the short run. Political and regulatory pressures may slow deployment, particularly around data centres and power usage.

These frictions affect timing and distribution, not direction. They may delay benefits or make them uneven, but they do not undermine the underlying economic logic of AI as a productivity-enhancing technology.

A slow-burn transformation

AI is best understood not as a single technological event, but as a long, capital-intensive economic transition. The early chapters of the modern era are being written through investment and demand, not instant efficiency gains. Over time, as adoption spreads and organisations adapt, productivity gains are likely to become more visible.

History suggests patience is essential. The technologies that matter most economically rarely deliver immediate gratification. AI appears to be following that familiar path – one that reshapes investment first, productivity later, and growth throughout.

From an investment perspective, this history argues for cautious optimism today. The underlying momentum behind AI diffusion across the economy continues to build, but the range of possible outcomes is wide and the journey unlikely to be smooth. In this environment, discipline, close observation, and a grounded historical perspective are essential.

[1] https://register-of-charities.charitycommission.gov.uk/en/sectordata/

sector-overview

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/September_2022_United_ Kingdom_mini-budget

Important information

This document is intended for retail investors and/or private clients. You should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been issued by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859, and which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111.

This document has been prepared for marketing and information purposes only and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the material is based has been obtained in good faith, from sources that we believe to be reliable, but we have not independently verified such information and we make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

This document should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

The value of investments and any income derived from them can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. If investing in foreign currencies, the return in the investor’s reference currency may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results and may not be repeated. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of their own judgement. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document.

Where the data in this document comes partially from third-party sources the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information contained in this publication is not guaranteed, and third-party data is provided without any warranties of any kind. Sarasin & Partners LLP shall have no liability in connection with third-party data.

© 2026 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP. Please contact [email protected].