On 24 February, the world woke up to the shock and horror of Russian tanks rolling into Ukraine. It is impossible to be unaffected in the face of such high potential for loss of human life – we are all people before we are investors.

The invasion has, remarkably, not been reflected too severely in world markets so far. Yes, volatility has been high, but after rallying on Friday, the S&P 500 actually ended last week slightly higher than where it started. The US Dollar Index (DXY) has risen by little more than a percent, while credit spreads have widened, but only modestly. Even gold was little changed on the week. Such a comparatively sanguine response to such an appalling geopolitical shock is not, as it turns out, unusual. In fact, equity markets tend, ironically, to rise in the aftermath of military conflicts.

The impact on domestic Russian markets has been devastating, however. Not only have equity markets and the rouble collapsed, but the cost of insuring government debt now indicates a 56% chance of sovereign default1. The cause has been a raft of much stronger and more united sanctions from the West. Particular impact came from sanctions on the Russian Central Bank, controls on a wide array of technology exports – including civilian aircraft spare parts – as well as the suspension of several Russian banks from the global payment system SWIFT.

Against this backdrop, the key risk for Western markets is probably escalation. Does the conflict widen out from Ukraine, will Russia dramatically constrain gas exports, and what do Putin’s chilling words about ‘high nuclear alert’ really mean?

The history of military conflicts supports the measured reaction of markets seen so far

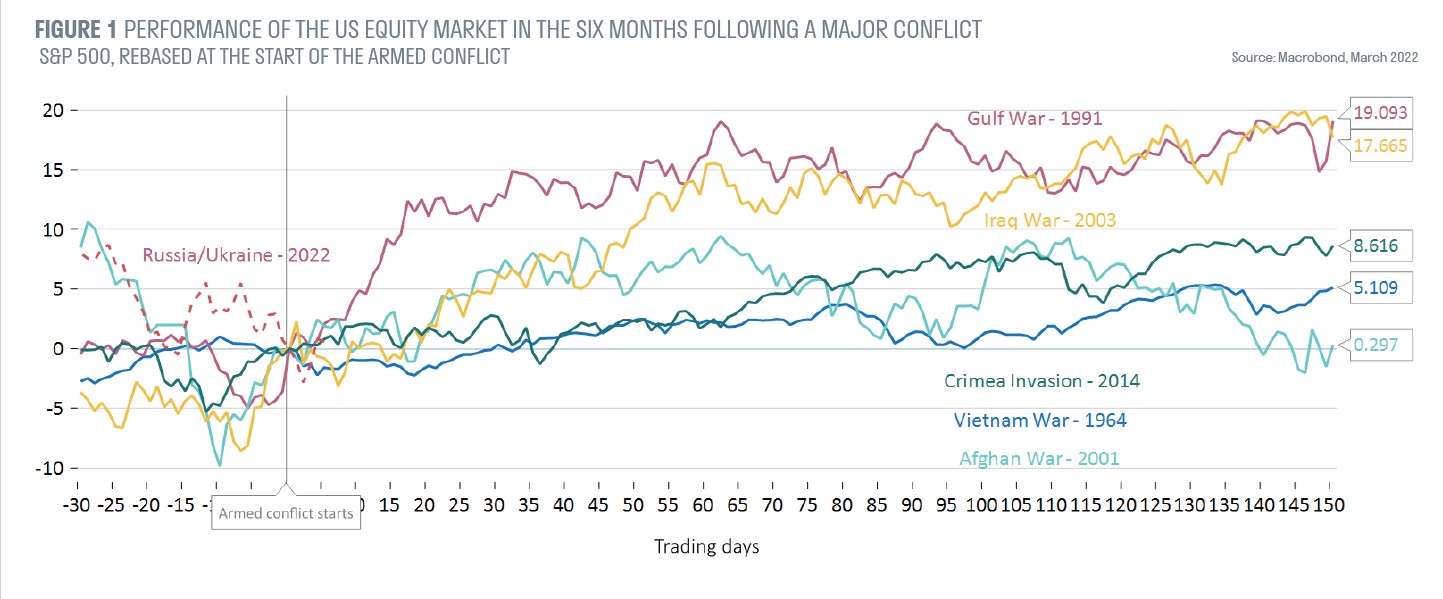

The immediate reaction of equity markets to the invasion broadly fits the pattern of previous military crises (chart 1). In the six examples highlighted since 1964, most saw flat returns over the first month of conflict, while all saw markets reach higher over six months. Interestingly, this includes the 1991 Gulf War, where global energy supplies were also clearly at risk.

For this comparative market stability to continue, there are however some important assumptions to be made. First, the Federal Reserve has a track record of pausing tightening or at least responding more dovishly to short-term shocks, and we assume this applies today. It certainly suggests talk of a half point rise at next month’s FOMC meeting is now unlikely, but we still expect five US rate rises in 2022. Certainly, other central bankers have already appeared more dovish. ECB member Robert Holzmann probably spoke for many last week when he indicated a move to normalise policy remains likely, but that ‘the speed may be somewhat delayed’.

The second assumption is that gas exports from Russia to Europe continue to flow. Indeed, the Russian need for foreign exchange revenues may ensure this. Third, as we mentioned, is the risk of escalation. Already, Belarus is acting as an arm of the Russian state, while the decision by the EU, US and UK to supply arms to Ukraine could easily be used as a pretext for Putin to widen the crisis. Note, too, the possibility, albeit unlikely, of de-escalation. The peace talks may succeed, or perhaps Putin’s unconstrained control of policy is challenged back in Moscow.

To insulate against any contagion from the crisis, it seems prudent that investor portfolios reflect high-quality, cash-rich global equities with zero direct exposure to Russian assets, a low exposure to emerging markets and no junk or low-rated debt. High exposure to renewable projects also seems a smart move, as does holding cash, short-dated bonds and gold, which provide a buffer from volatility. While it is near impossible to avoid the declines in markets in 2022, these adjustments ensure portfolios are robust and drawdowns limited.

Our first conclusion is global inflation will be stickier for longer than many had expected. If the crisis is prolonged, then stagflation is clearly a risk.

The longer-term impact

In the longer term, perhaps the right global parallel for the invasion of Ukraine is 9/11 – a single event that determined government, foreign and military policies for years to come. The implications of course are multiple today, but it seems three particular areas will have an impact on financial markets:

- First, the invasion of Ukraine has come at a difficult time for the global economy. Prices, in the aftermath of the pandemic, are already rising at levels not seen in 40 years. Russia, meanwhile, is the world’s largest producer of gas and one of its largest oil producers. It will also potentially become one of the biggest exporters of grains, soybeans and sunflower oil if it gains control of Ukraine’s rich soil. The United Nations releases its monthly food index on Thursday, and this may already show prices above 2011 levels – a year when skyrocketing food costs contributed to political uprisings in Egypt and Libya. In short, the impact on price levels could become a unique challenge for global central banks and could, if allowed to persist, raise the risk of stagflation. The possible parallels with the 1970s oil price shock in the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War provide a worrying precedent.

- Second, with Poland, Hungary and five other NATO members potentially sharing a border with a new, expanded Russia, the ability of the US and NATO to defend the alliance’s eastern flank could be seriously challenged. The result will be an end to the post-Cold War ‘Peace Dividend’, requiring a surge in military spending by European NATO members. Already, Germany has pledged 100 billion euros to modernise its Bundeswehr armed force, an act of extraordinary political significance for the country. Russia by contrast will continue to seek a two-tier NATO, in which only limited allied forces are deployed on former Warsaw Pact territory. Pursuing this agenda could result in regular flash points along NATO borders, ongoing cyber hostility and increased risk of escalation – this means heightened geopolitical risk for an extended period. One small positive has emerged – the European Union has finally found a decisive and united voice on the world stage. The organisation and its institutions have typically grown stronger during crises – fiscal integration, for example, finally became a reality during COVID. The current crisis is proving no exception.

- Third, the fragmentation of global supply chains and cross border trade can only be further exacerbated. Already, the internet, social media space and many technologies are divided between Russia and the West. Today an Iron Curtain has fallen on the Russian internet and, through far-reaching export controls, on Russian access to global technology, especially high-end semiconductors. China, of course, will still be a supplier. In fact, it could effectively take 100% control over Russia’s technology needs. For global manufacturers though, it is yet another reason to shorten supply chains, bolster domestic production facilities and sacrifice margins in return for security of supply – shareholders will inevitably suffer.

What does this mean for longer-term strategy?

Our first conclusion is global inflation will be stickier for longer than many had expected. If the crisis is prolonged, then stagflation is clearly a risk. This should encourage investors to keep bond weightings low, despite the asset’s normal role as a haven during conflict.

Second, the crisis is likely to depress growth, sustain uncertainty and damage consumer and business confidence. This suggests risks for credit markets and argues for a bias to robust cash flow and quality across equity selection. Dividend-paying equities meeting these criteria become a powerful alternative to bonds.

Third, the risk of further escalation and ongoing tension at NATO’s eastern borders argues for higher cash positions, portfolio insurance where permitted, and long-term strategic positions in gold – all defensive measures that may be required for some time.

Fourth and finally, a rush to improve energy security across Europe will accelerate the switch to renewables, and, ironically, could further empower the climate agenda. Demand will be strong for renewable generators, rail infrastructure, building efficiency and electrification of transport systems – areas in which Europe excels.

In all of the above, investors must recognise circumstances are developing with remarkable speed. In the immediate future, only one thing is certain – the remarkable fortitude and bravery of our Ukrainian allies and friends.

1Source: Bloomberg, 25 February 2022