Key points:

- High supply of bonds is here to stay as governments continue to spend heavily, and they are financing this by debt.

- Demand for government bonds is structurally weaker as key buyers, such as defined benefit pension funds and central banks, have retreated.

- Supply strategies are key: with persistent deficits and elevated issuance needs, governments must adapt by shortening maturities, and aligning issuance more closely with evolving investor demand. We expect this adjustment to gather pace.

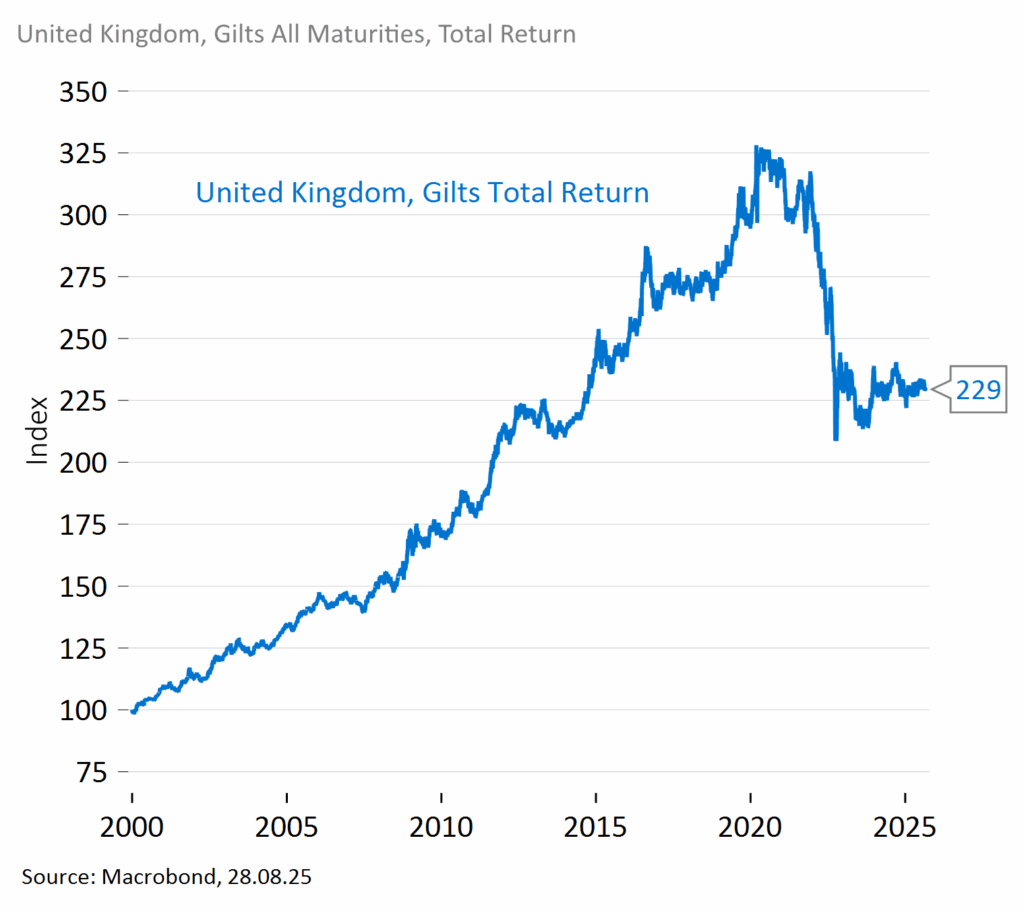

In the Q3 2025 edition of the House Report, we discussed the concept of bond market regimes. In short, these are periods of time where bonds exhibit similar characteristics – both on a standalone basis and in terms of their role in a portfolio. We believe there have been three significant regimes since the 1960s. Each lasting around 20 years. With the higher interest rates we have seen since 2022, we may be entering a fourth. Time will tell.

Having previously challenged some common myths around government bonds, here we dive into one of the most fundamental changes in the landscape: the supply-demand balance being upended.

It is no secret that governments around the world are spending big. From January to June 2025, the US federal government spent $3.6trn, while both the UK and Germany are upping spend on defence and infrastructure. Of course, high government spending equals high deficits and those deficits are financed by the government selling more bonds. But to whom?

Let’s take a look at what this means for demand, supply, and bond ownership going forward.

The golden era of bond demand?

First, a step back. For many years the going was good for debt management offices (those responsible for selling government bonds) with strong demand for bonds from a variety of sources.

Investors scarred from the negative equity markets in 2008 wanted their fill. Pension schemes were a large buyer, particularly of long-dated and inflation-linked bonds. This was especially the case during the decade post the great financial crisis where quantitative easing (QE) was prevalent, with large-scale central bank buying of government bonds at almost any price.

Indeed, based on the strong returns delivered in the first 20 years of this millennium one could quite comfortable argue there was excess demand for bonds.

So where are those buyers now?

Pension funds are retreating

A major buyer has pulled back: defined benefit (DB) pension schemes. In the UK a recent publication by the OBR highlights this point starkly.

The shift from defined benefit to defined contribution (also known as money purchase) schemes has been well documented. But the impact on demand for gilts is significant. According to the OBR, 40% of defined benefit pension assets are gilts. For newer style DC pension the figure is just 7%.

But that shift will take a long time, right? Not according to Legal and General, which reported that a record number of DB pension funds closed to new accruals or transferred liabilities to insurers in 2024. That trend is widely expected to continue.

In short, this means less demand for government bonds.

The new regime: QT and inflation fears

Central banks are not buying either. Faced with the most persistent inflation in decades, central banks have switched course. QE has given way to QT (quantitative tightening) where holdings are allowed to mature or actively sold. Sure, QT is closer to the end than the start, but the point remains, active new purchases by central banks is a long way off.

The result? Another of the largest sources of consistent bond demand has disappeared, and this trend is unlikely to change anytime soon. With inflation remaining a live concern and remaining above targets, central banks are now structurally more cautious about adding to their balance sheets.

So, should you sell all your bonds then? Not so fast…

The answer lies in supply, not demand

Rather than declaring the death of the bond market, we need to think differently about how the market adjusts.

Historically, bond issuance was often demand driven. Governments issued longer-dated bonds to match pension funds’ liability driven demand, or structured auctions to align with central bank operations. But today, the demand side has weakened, and yet issuance remains high, especially given growing fiscal pressures.

This calls for a supply-side rethink.

Governments and debt management offices need to adjust the composition of their issuance. Shorter maturities, careful consideration of inflation-linked debt or more flexible auctions could help absorb the supply more effectively. Just as corporates adjust to investor demand in markets, governments may have to do the same with their debt strategies.

We have seen action to this effect already. In the US, the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) has taken notable steps since 2022 to reduce the proportion of long-dated issuance and increase reliance on short-dated Treasury bills. Similarly, in the UK, the Debt Management Office (DMO) has started the process of shortening the average maturity of new bond issuance.

So, bonds aren’t dead – but regime awareness is critical

The disappearance of QE and retreat of pension funds does not make bonds uninvestable. However, it does mean we are in a different world – one where pricing is more sensitive, liquidity is more fragmented, and supply discipline matters.

The key for investors is to focus on the dynamics that now drive bond markets: who the marginal buyer is, how supply is being managed, and where genuine demand still exists. Regime awareness, as we have argued before, is no longer optional – it is essential.

We should not forget that bonds still have many favourable characteristics. Stability of income is one that many of our clients consider important; with yields far higher than they have been for many years, the income angle remains as relevant as ever.

Sarasin’s allocation to bonds

How is Sarasin responding in client portfolios? The answer is threefold.

- We are not throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Bonds still have a role to play in portfolios. Our last article covered this point.

- However, just as institutions like the Debt Management Office need to adapt, so do we. Here’s how:

- In portfolios that target CPI+1 returns, we have reacted by shortening the average maturity of the bonds we own materially. These portfolios have the highest government bond allocation of all accounts we manage, so were most exposed.

- In portfolios with higher return targets, we are actively reviewing the maturities of bonds we own, carefully balancing all of our analysis.

- We are being more selective than ever. Change breeds opportunity, and we must remain alert to this.

Bonds continue to play an important role in client portfolios, and this is unlikely to change anytime soon. As with equities, an actively managed allocation to bonds – with a wider understanding of the trends and regimes impacting supply and demand – is vital to delivering the best long-term outcomes.

Important information

This document is intended for retail investors and/or private clients. You should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been issued by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859, and which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111.

This document has been prepared for marketing and information purposes only and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the material is based has been obtained in good faith, from sources that we believe to be reliable, but we have not independently verified such information and we make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

This document should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

The value of investments and any income derived from them can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. If investing in foreign currencies, the return in the investor’s reference currency may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results and may not be repeated. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of their own judgement. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document.

Where the data in this document comes partially from third-party sources the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information contained in this publication is not guaranteed, and third-party data is provided without any warranties of any kind. Sarasin & Partners LLP shall have no liability in connection with third-party data.

© 2025 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP. Please contact [email protected].