"I am more concerned about the return of my money than the return on my money”. Mark Twain’s historic remark no doubt continues to resonate with many a charity executive trying to build some level of certainty into their financial forecast over the period ahead.

And yet, with interest rates sitting stubbornly low (0.1% in this country1) and short-term inflation rising rather more quickly than is palatable, many of us are questioning how we might invest shorter-term monies. Is there an alternative to cash? How much risk should we take to squeeze out a little bit more return?

Bonds have performed well over the last few decades

Although we have been living with low rates for several decades, this steady decline in interest rates (and subsequent bond yields) has led to some strong investment returns from the market’s ‘safest’ assets: bonds. Indeed, investors with short- and medium-term liabilities and those who have adopted lower risk, multi-asset strategies, have effectively had their cake and eaten it. Attractive returns have been achieved with only occasional bouts of volatility.

Not only have government and corporate bonds produced remarkably consistent and positive returns, but the fact that many medium-term strategies often include a small allocation to equities, means their returns have been boosted further. The financial repressive policies in place since the financial crisis and enhanced to combat COVID -19 have ensured that a few sharp and severe drawdowns in capital values have been restored remarkably quickly. So, what’s wrong with that, one might ask?

There is now a real danger that we have been lulled into a false sense of security, whereby we believe that our short- and medium-term (mostly) bond portfolios will keep on delivering.

Past performance, a reliable guide to the future?

We often write articles promoting the use of historic returns as an example of how different asset classes might behave in the future. But this is the problem. Human nature will lead investors to extrapolate history, particularly when a trend had been evident for a decade or longer, in the expectation that the trend will continue. In today’s marketplace, the dangers are heightened for investors with short and medium-term requirements: the ‘pull’ to do something inappropriate is not just driven by the attractive returns that have been achieved with relatively little risk, but also by the ‘push’ of the safer options (cash) being so deeply unattractive.

Against this backdrop, we thought it might be helpful to set out the options available to investors looking to invest their short- and medium-term monies, making clear the risks of each solution and unfortunately, in many instances, concluding that cash is still likely to be the best option even if returns over the next year or two result in negative ‘real’ (after inflation) returns. But there are certainly some alternatives.

We should probably clarify at this point that short-term monies are anything from an immediate cash need to about 18 months out. Medium-term monies are generally 18 months to 3 years, but can extend further out, depending on the degree of certainty built into one’s cashflow projections. It is also important to note that, at the time of writing, the 10-year government bond yield in Europe remains negative, is negligible in Japan, 0.8% in the UK and 1.4% in the US2. And that is ten years out!

Shorter-term monies, what are your options?

Cash: either held in one bank, diversified across a few banks, or invested in a diversified cash fund. The interest rate is unlikely to be much more than that of the Bank of England base rate which means that your capital value will steadily erode over time, even with very low levels of inflation. Whilst interest rates could possibly even rise as early as 2022, they have a long way to go before they produce a meaningful return. However, one holds cash in exchange for certainty: “the return of my money”.

Short-dated government bonds: Unfortunately, there is almost no benefit to holding a portfolio of short-dated government bonds. You are probably better holding cash as your yield is the same and your capital is more secure.

Short to medium term corporate bonds: This is certainly an option for some. The yield and real return on a portfolio of 3-year bonds is more attractive than cash but here the dynamics are starting to change and your risk profile is rising. Firstly, you need significant scale to build a well-diversified corporate bond portfolio, as it is important to avoid the risk of a default. Secondly, there is always the possibility – albeit remote – of liquidity drying up and not being able to sell your holding when you need to.

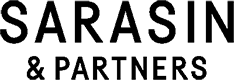

A classic corporate bond portfolio with a range of maturities, both long and short: Again, this might well be a sensible option as long as one is aware of the risks noted above which are, of course, greater given the additional yield you are likely to achieve from investing in longer dated issues. A typical corporate bond portfolio today could yield as much as 3.1% with a duration of 8 years3. Certainly, a step up from cash, but your capital in this portfolio could be hit hard if interest rates rise unexpectedly.

A multi-asset reserves portfolio: This is predominantly made up of government and corporate bonds, but probably diversifies into other assets such as equities and alternatives to provide additional return. The Sarasin Income & Reserves strategy aims to achieve inflation (CPI) +1% over an 18 month to 5-year period. However, should interest rates rise unexpectedly, the impact of a simultaneous bond and equity sell-off would be painful.

A target return portfolio: A slightly different approach to multi-asset investing is to target a specific level of return (e.g. inflation +2%). This could be achieved with a multi-asset portfolio, but one which carries a bit more equity risk combined with the judicious use of portfolio insurance (to help protect capital values in the event of a market sell-off). The portfolio is actively managed to try to avoid downside risk. This has worked well in the past and with volatility having fallen back (the VIX is at 15.1)4 portfolio insurance today is reasonably inexpensive. Two important points to make here: you are placing significant faith in your manager to move nimbly in the marketplace, and you certainly need a slightly longer timeframe for this portfolio. This strategy can work well if you allocate more to a cash portfolio than you might have done previously and then agree to place some funds in a target return portfolio which carries more risk but should deliver a better return over time.

Lower returns but limited losses - weighing up risk and return

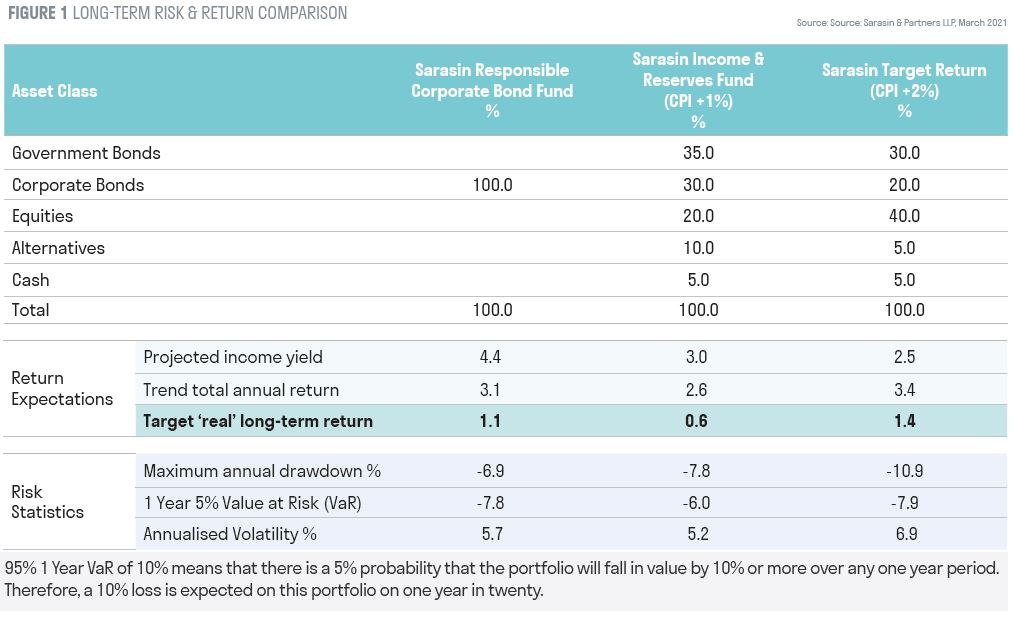

In conclusion, it will come as no surprise to hear us say that there is no golden bullet. It is always possible to achieve additional return but this inevitably involves extra risk. It is essential to identify that risk; even though it hasn’t been prevalent recently, it doesn’t mean it has disappeared altogether. Sometimes it is better to acknowledge that losing 1% or 2% a year in real terms might be unappealing but it is still significantly better than losing 10% or worse still, being unable to access your money at all. Whilst it may come as a surprise to watch European investors soak up large volumes of short-term bonds issued with negative yields, perhaps the reason they are willing to pay this price is knowing that their losses are limited.

It is arguably more important than ever to forecast your cash requirements as much as is possible over the next few years. Understand your timeframe and speak to your investment manager about the different solutions available to you. If you can take a little more risk, it might well make sense to do so, but in the knowledge that we are at a dangerous point in markets given how low interest rates and bond yields have fallen. Should bond yields rise more quickly than investors expect, those investing with too much duration for their liquidity needs could get caught out. As ever, it is a fine balance between accepting the negligible returns from safer assets (cash and short-dated government bonds) or pursuing higher returns from riskier asset classes (long-dated corporate bonds and equities) and risking the possibility of losing precious capital.

Today more than ever, what to do with shorter-term monies requires meticulous cashflow planning.