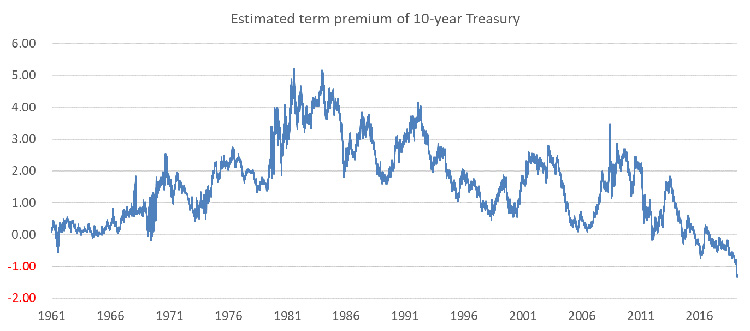

An important caveat applies when it comes to using the yield curve slope as a recession predictor. The clarity of the signal may be a little blurred this time around by the fact that the ‘term premium’ embedded in government bond yields is deeply negative at present. As a reminder, term premium is a function of all the other ‘stuff’, besides the Federal Reserve’s short-term interest rate policy, which impacts long-term rates.

For those who like a more technical definition, term premium is the extra yield you earn by lending for a single 10-year term over and above what you would have earned lending for one year, and then successively re-lending for another nine one-year terms. Overall you ought to earn more for doing the former, given the amount of uncertainty inherent in lending for such a long term, as opposed to repeatedly lending on a shorter time-frame with correspondingly greater visibility regarding the likelihood of repayment.

What are the drivers behind term premium?

- One typical driver is inflation premium, which explains why term premium was so large back in the 1970s and early 1980s. Inflation premium has declined substantially since the inflation-busting policies of the Volcker Fed in the early 1980s

- Another is the global ‘savings glut’, as it was dubbed by Ben Bernanke back in the mid-2000s. This refers to the huge build-up of precautionary savings (in the form of accumulated current account surpluses) by Asian trading nations in the years following the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-98.This led to an excess of global savings over global desired investment, which further depressed term premium. The result was what Alan Greenspan famously described as ‘the conundrum’, namely the observed phenomenon that progressive increases in the Fed Funds rate failed to drive long-term interest rates higher (tighter Fed policy was met by the recycling of Asian current account surpluses into the US fixed income market, holding long-term interest rates at relatively low levels).

- In the last decade, quantitative easing (QE) has been the strongest influence on term premium, driving it to all-time lows as the chart below illustrates:

So how likely is a recession?

The globalisation of fixed income markets has only increased with time. Huge pools of capital sitting in countries like China, Japan, Taiwan and Switzerland can be readily re-deployed between international bond markets to capture changes in relative term premium. Hence even if the Fed has stopped QE, the flattening of yield curves in foreign markets owing to the promise of exceptional monetary easing (Japan has never stopped since QE and the ECB appears poised to resume the QE programme it concluded at the end of 2018) will rapidly spill over into US bond markets. Bizarrely, a flattening of the German bund curve due to expectations of ECB QE could therefore rapidly translate to a higher probability of US recession as implied by the US yield curve!

The bottom line is that whilst we should exercise appropriate caution in the face of the signal sent by the yield curve shape, things may be actually be less bad than they appear. A traditional estimate of US recession probability, based on probit regression of the periods of US recession on US yield curve shape, implies it is a material risk within the next year and all but inevitable within the next three years. A ‘term premium-adjusted’ estimate, on the other hand, implies perhaps only a 50% probability of recession within the next 3 years. The truth lies somewhere in between.

These are the views of the author at time of publication and this does not constitute a recommendation to buy or sell any security. The information in this article does not qualify as an investment recommendation or investment advice.