2022 was billed as the year when life would “return to normal” after the disruption caused by COVID-19.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has put paid to any hopes for normality, but three familiar underlying themes will continue to dominate geopolitics and the global economy for some time to come.

On 24 February, Russian tanks entered Ukraine in an act of war that will affect geopolitics, military alignments, trade alliances and currency regimes for years to come.

One thing is clear. The post-Cold War peace dividend that brought prosperity to so many nations has been squandered by an autocratic and revanchist regime. Less clear is the path that geopolitics, economics, trade and finance will take as demand and supply patterns that were disrupted by the pandemic face further multi-year shifts.

We do have some reliable guidance. The pandemic and the war reinforce and amplify three salient themes that were already underway in the world economy.

These are:

- Accelerated adoption of new technologies.

- A mounting imperative to share prosperity more widely.

- De-globalisation caused by competition between liberal democracies and autocratic regimes.

Tech-celeration and the pandemic leapfrog

Just three months after the pandemic hit, 'Zoom' entered the Oxford English Dictionary, a reflection of the technological leapfrogging that has occurred as businesses and households have been forced to embrace next-generation technologies.

Now, investment in automation and digitalisation is being driven by extreme tightness in labour markets. Employment usually takes time to recover after a recession – almost a decade in the case of the 2008 global financial crisis. After COVID-19 it took just 20 months. Any capacity left in labour markets has been wrung out over the past year as businesses compete for workers, and upward pressure on wages is encouraging digitalisation and automation in a bid to mitigate labour costs. A further strand of tech-celeration lies in the restructuring of supply chains. Lockdowns created huge gyrations in consumer demand, and complex global supply chains were unable to cope. The resulting shortages and disruptions will be exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. In response, businesses are endeavouring to ensure resilience in supply chains by bringing them closer to home, building redundancies into supply networks and increasing supply chain automation.

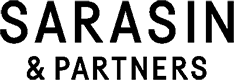

A further strand of tech-celeration lies in the restructuring of supply chains. Lockdowns created huge gyrations in consumer demand, and complex global supply chains were unable to cope. The resulting shortages and disruptions will be exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. In response, businesses are endeavouring to ensure resilience in supply chains by bringing them closer to home, building redundancies into supply networks and increasing supply chain automation.

Sharing prosperity

The second theme that will emerge stronger in the post-pandemic world is a concerted effort to share the gains of prosperity more equally with those who have not benefited from globalisation and advances in technology.

Over the past two decades, the capital base of western economies has undergone dramatic transformation. Businesses have shifted their spending away from long-duration investment in areas such as factories and transportation in favour of shorter-duration expenditure in information processing and intellectual property.

Again, this has meaningful consequences for the labour market. Digitalisation and automation reduce demand for lower-skilled roles, widening the gap between haves and have-nots and providing fertile ground for populist policies at both ends of the political spectrum.

The traditional remedy for inequality is to tax the rich more and transfer wealth to the less well off, but this is unlikely to be the path that politicians choose. As we have seen in the US, the Biden administration struggled to achieve tax increases, despite enacting fiscal stimulus of almost $2.5tn.

Instead, we anticipate measures designed to level the playing field, such as greater investment in health, education and infrastructure. However, higher levels of social spending without commensurate tax increases mean that fiscal deficits are likely to rise.

Global rivalry is growing

A third, and possibly the most impactful trend, will be escalating competition between the liberal democracies and the more autocratic regimes of Russia and China. This will spill over into global trade, finance, defence and security arrangements.

Since the end of the Cold War we have enjoyed a peace dividend that brought prosperity and, with the integration of Eastern Europe and China into global trade, tremendous improvements in living standards. Alongside these advances, rivalry between China and the US has grown. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has pulled China closer to Russia and brought out into the open the conflict between liberal democracies and autocracies.

We are entering an era of Great Power competition, where security and defence arrangements will be restructured and the globalised market for trade and finance will pull apart. Moreover, the aggressive use of financial sanctions has turned the dollar payments system into a tool of war. Autocracies, which own roughly half of the $20tn in global reserves held by central banks and sovereign wealth funds, are currently vulnerable to financial sanctions that work primarily via US dollar payment systems. Over time, however, sanctions will incentivise the adoption of alternative payments systems that bypass western banks. Trade will follow the shifts in finance, with imports and exports gravitating towards allies. The US dollar’s dominance may therefore be eroded unless the US ramps up its use of soft power to win over allies.

Trade will follow the shifts in finance, with imports and exports gravitating towards allies. The US dollar’s dominance may therefore be eroded unless the US ramps up its use of soft power to win over allies.

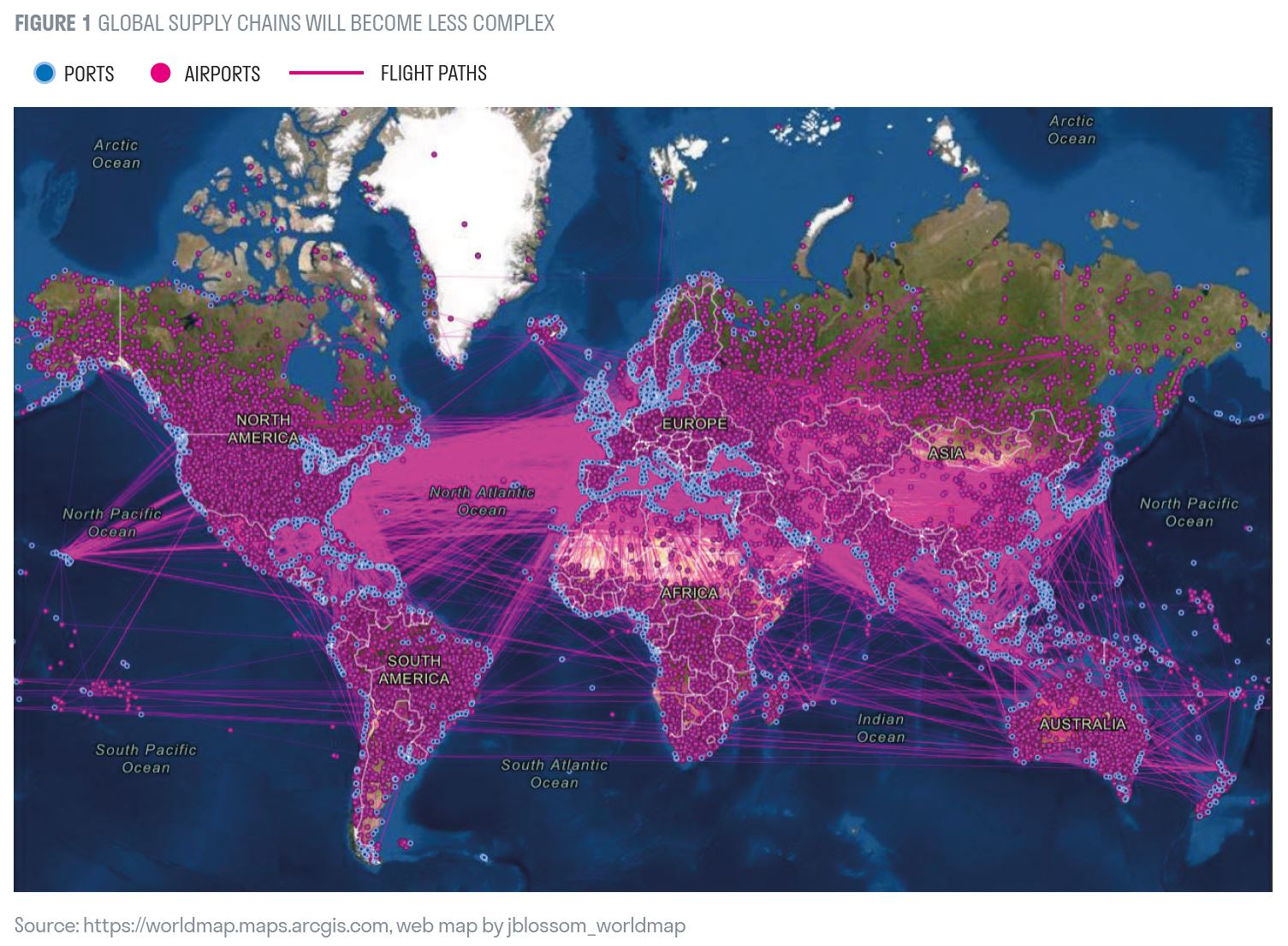

As Great Power competition heats up, defence spending will rise across the world. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, defence spending halved across much of the West. Now, a looming long-term conflict with autocratic regimes suggests a multi-year pick-up in defence spending.

The great moderation is ending

Tech-celeration, levelling up and great power competition will together create an environment of enormous flux; the Great Moderation, whereby volatility in economic activity and inflation consistently trended lower, is ending. In its place, we can expect shifts in activity as the state expands, technology grows more powerful and new alliances are formed.

With higher spending on defence, energy security, energy transition, health and education in the pipeline, pressure on public finances will grow and debt levels risk becoming unsustainably high.

Pandemics and war are inflationary because they disrupt supply much more than demand. We expect inflation to moderate as supply chains normalise, but not return to pre-pandemic levels. Instead, we expect inflation to run at 2.5-3% over the medium term. The risks are clearly to the upside. If the supply side of the world economy remains impaired due to persistent shocks, inflation expectations will rise and we may see wage inflation drive price inflation.

Although central banks are keen to dampen inflation, interest rates are likely to remain relatively low.

This is to help manage the interest burden of high debt levels and rising deficits. At the same time, central banks are likely to tolerate moderate overshoots of inflation targets to reduce the real value of debt, while governments are likely to use regulatory powers to ensure that banks remain significant buyers of local government debt.

A time for active management

We are entering an era of tremendous flux as adoption of new technologies accelerates, supply chains are restructured, government spending increases and geopolitical tensions rise.

We expect inflation to ease back from its current peaks, but investors must learn to live with elevated inflation and seek out real assets that have the potential to protect against its corrosive effects. The coming years will be a more volatile environment for growth. In such conditions we can expect greater dispersion between winners and losers that rewards well-researched, focused active management.