The announcement that Roche’s antibody test has been approved by Public Health England represents a significant step in fighting coronavirus. While it is not yet clear to what extent having had the virus gives immunity against catching it again, an effective antibody test is a positive development.

Six months ago, the development of an antibody test for coronavirus would not have inspired such great global interest. However, a large portion of the world has sadly had to become very familiar with virology, epidemiology and our immune systems over the few months. Bearing in mind the latest development from Roche, where are we now with COVID testing, vaccine development and potential therapies? What follows is an attempt to capture the current state of play for the three main areas of COVID research, with an acknowledgement that this is a dynamic area full of unknowns.

The evolution of COVID testing

The bulk of current testing involves using a swab to collect tissue, which is then tested for COVID nucleic acids. These tests are extremely effective and can test definitively for the virus. So what’s the problem? Capacity – relative to this massive demand – has been slow to respond. Furthermore, these tests only establish if you currently have COVID antigens. They are unable to determine whether you have had it and now have some immunity to the disease.

The recent news from Roche is significant. Antibody tests show if you have been exposed to COVID and may have developed some immunity. There are two broad classes of antibodies that respond to COVID. The first is IgM, which is the biggest and most rapidly reacting antibody. Levels of IgM typically spike in the first five days of a viral infection. The second responding antibody, IgG, gives the patient longer lasting immunity. There are tests available that will broadly point to the existence of IgG and IgM antibodies consistent with COVID exposure and immunity. Roche’s test is 100% sensitive in picking up both IgG and IgM antibodies consistent with COVID exposure and 98.8% specific, meaning that only 0.2% of the time will the antibodies it picks up be for a coronavirus that is not COVID-19. It can easily be used by hospitals and laboratories around the world.

Antibody testing: Roche’s test has now been approved and already has orders from around the world

When will a vaccine be found?

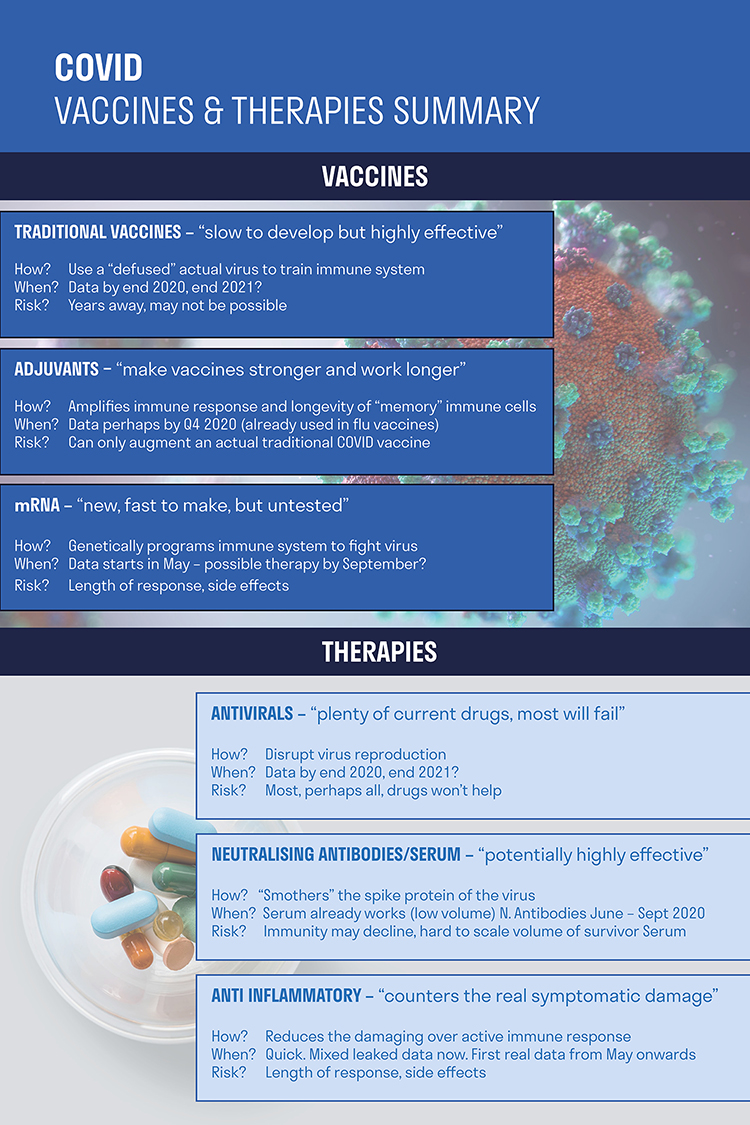

Remarkable things have happened already in vaccine development. Traditional vaccines use an actual virus sample to train a person’s immune system to respond to it. They are highly effective but extremely slow to develop. Messenger RNA or mRNA vaccines are different – they genetically programme one’s immune system to fight the virus. mRNA vaccines are untested in humans but they are much faster to make. In addition to traditional and mRNA vaccines, another promising area of research is around adjuvants – they amplify the immune response, making traditional vaccines stronger and work for longer.

Healthcare company Moderna has managed to progress from genetic information to mRNA vaccine dose in 42 days, versus 5 – 10 years or longer for a typical vaccine. However, there is no guarantee that a vaccine will ever be found – there are currently no vaccines for any coronavirus and even after decades of study there remain no vaccines for viruses such as HIV.

The number of vaccine candidates has, unsurprisingly, ballooned. In January, there were 20. There are now over 80. Most target the spike protein. The spike protein sticks out from the body of the virus and functions as an anchor to the target cell and is the reason why the virus looks a bit like a crown. Its crown-like appearance is the origin of its name, coronavirus.

There is currently a superhuman effort to get these vaccines through testing with the FDA and other regulators. Progress so far has been remarkable, given that it usually takes 10 – 15 years or longer to develop a vaccine. Moderna has now started trials of its new messenger vaccine. Meanwhile, other companies such as Pfizer and Sanofi are also progressing with mRNA vaccines and longer term, Johnson and Johnson could present early data from a more traditionally synthesised vaccine as early as Q3.

An effective vaccine: Could be one year or more away, or may even prove completely elusive

What about therapies?

When considering therapies it is necessary to understand the development of COVID. As far as we know the total cycle typically lasts 28 days and can be put into three separate phases.

- Phase 1 – initial symptoms – the virus is starting to replicate often in the back of the throat and the immune system is starting to kick in with a spike in the levels of IgM

- Phase 2 – pulmonary stage – the viral load increases significantly and the virus spreads into the lungs, making the patient susceptible to secondary infections.

- Phase 3 – hyper-inflammation stage – less about the virus but more about cytokine release systems, via IL6 for example, which mainly affects the lungs but seems to have an impact on other organs too.

There are many therapies that are being repurposed to try and help with each of these phases. Antivirals are one category. These disrupt virus reproduction. Remdesivir from Gilead has accumulated good safety data and could prove helpful by reducing the viral load. A possible effect could be to shorten the time in ICU by one to two days which could see a 10% - 15% drop in ICU demand.

Other drug candidates to lower viral load have been widely touted – Chloroquine and Hydro-chloroquine – both of which are currently approved against malaria and lupus. There have been trials showing some early promise; a recent trial conducted in France was encouraging but was however not measured against a control population.

Neutralising antibodies are another promising area. These smother the spike protein of the virus and could potentially be highly effective.

To counter the hyper-inflammation phase there are a variety of well-established anti-inflammatory drugs, such as Roche’s Actemra, that are already approved in other areas such as rheumatoid arthritis.

A toolkit of therapies but one that might work: autumn 2020

With the world’s attention on COVID, medical and scientific communities around the world are consolidating their efforts on tests, therapies and vaccines. While we are relatively close to developing an antibody test and finding effective therapies, a vaccine will take much longer to materialise and may never be found. What does this mean? Social distancing practices are likely to stay in place for longer, but antibody testing will make it possible to identify those likely to have long-term immunity, who are able to resume normal economic and social behaviour. Effective therapies will reduce the load on hospitals, increasing survival rates and lowering the fear factor.

Companies at the forefront of the fight against COVID are likely to benefit from increased governmental and investor support. We own a number of these promising names in our portfolios, such as Roche, Amgen, Novartis and Shionogi, and are following their progress with much interest.