Towards the end of 2017 the BBC’s Blue Planet II series was broadcast around the world. It helped open the eyes of billions of people to the appalling destruction of marine life from irresponsible disposal of plastics.

Many of us now want to rethink our use of plastics, even if the economic and behavioural shifts needed for more sustainable behaviour on waste disposal are very challenging. In this article, we explore how governments are likely to introduce new regulations, how consumers might change their habits and how the global supply chain, including major publicly listed companies, might be squeezed.

Plastic is a miracle material - light, flexible, waterproof, enduring, virtually unbreakable and very cheap. From the spectacles on our noses to the socks on our toes, we use vast quantities of it – approaching 400 million tonnes globally this year.

It is endlessly useful, but its key fault is that plastic is endless: a PET plastic beverage bottle may take 450 years to break down.

The vast majority of all the plastic ever produced still exists (about 4.9 billion tonnes of it) but it has been put out of sight and out of mind. Now, however, the pictures of turtles caught in carrier bags or birds eating cotton buds have shown us a small part of the legacy of our wasteful plastic habit. A third of all plastics end up in fragile ecosystems like the oceans, 40% is buried in landfill and, of the remainder, most is burnt whilst only 5% globally is recycled.

A key issue in trying to tackle the problem in a market economy is that new plastic is too cheap. The utility value is high, while the raw material cost, closely related to the price of the oil feedstock, is very low. The small money cost of most plastic items means that they are discarded without financial penalty, encouraging single-use and breeding a throwaway culture. The low raw material cost also means that recycled plastic is more expensive than new plastic.

A second challenge is that the greatest growth in plastic use is occurring in countries with the worst waste-handling systems. Ten rivers, all in Asia plus the Nile and the Niger in Africa, account for over 90% of plastic polluting the world's oceans. However, we are not guiltless: although none of those rivers are in the EU, the European Commission estimates that up to 500,000 tonnes of plastic waste enter the oceans from the EU each year and much of this ends up in particularly vulnerable marine habitats such as the Mediterranean and the Arctic. The UK and other developed countries ‘outsource’ a large chunk of their waste recycling problem, to China until it banned such imports recently, and now to Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and Poland.

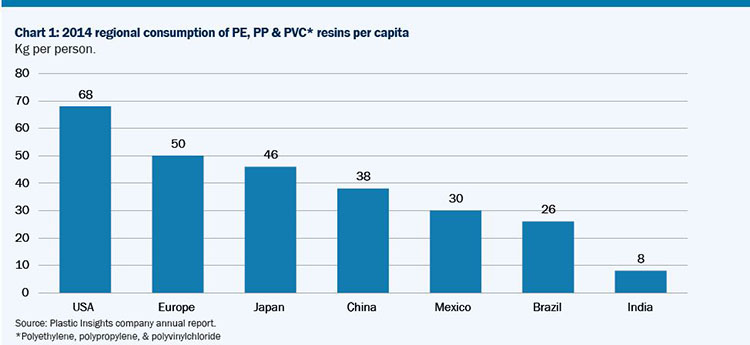

Many lower income countries are seeing rapid change in their plastic consumption as populations grow, wealth increases and diets change. An increase in plastic consumption by a large population like India (1.3 billion people currently using 8 kg per person per year) to European consumption levels (50 kg) or even to US levels (68 kg) will have a catastrophic environmental impact.

The nature of old plastic is particularly problematic. As it slowly degrades it breaks down into smaller particles, which in the oceans enter the food chain at every level and drop to the sea floor to form a layer of sludge. Many plastics also include added chemicals such as fire retardants, pigments, antibiotics, bisphenol-A (BPA) and phthalates (plasticizers). Of the estimated 150 million tonnes of plastics in the oceans today, 23 million are additives. The full impact of these is unknown but there is evidence that they upset hormone systems and cause other biological disruption.

Even in developed markets with effective municipal services to remove waste, the solutions are far from ideal. Landfill just hides the problem and leaves it for future generations to dig up. Burning plastic releases toxic gases and CO2 into the air and leaves ash waste residues which can contain concentrated pollutants. In the richest countries, new incinerator technologies, such as gasification, pyrolysis, and plasma arc, offer the prospect of lower-emission incineration but these are too complex and expensive to be used on a very large scale globally.

Government action

Data from the EU lists the major sources of plastic waste as packaging (39.9%); building (19.7%), automotive (8.9%) and electronics (5.8%). The current media focus, and the attention of consumers and governments, is on the largest category and in particular, single-use plastic packaging. Reuse and recycling of plastics is very low compared with paper, glass or metals and the volumes are enormous - worldwide, over a million plastic bottles are made every minute.

Governments around the world are implementing various strategies to begin tackling plastic litter, improve waste collection and encourage recycling. For example in the UK and many other countries, a ban on plastic microbeads in cosmetics products has just came into force. Following the lead taken by Denmark in 1993, taxes or bans on plastic carrier bags have been implemented in a large number of countries, including many poorer countries such as Somalia, Bangladesh, Rwanda and Ethiopia that are setting excellent examples to others.

The measures taken on plastic bags have helped raise awareness and reduce use. But the next steps on plastic policy need to be altogether more comprehensive. The European Commission has adopted an ‘Action Plan for a Circular Economy’ and in 2017 set a goal for all plastic packaging to be recyclable by 2030 and for more than half of plastics to be recycled. The UK government wants "to be the first generation to leave the environment in a better state than we found it". As part of this, it plans to eliminate avoidable plastic waste by 2042. DEFRA (the Department for Food and Rural Affairs) is working with WRAP (Waste and Resources Action Programme), together with the Ellen MacArthur Foundation New Plastics Economy initiative, to launch the UK Plastics Pact, with the aim that plastics never end up as waste. After assembling a ‘comprehensive evidence base’ the UK government, along with many others, plans to implement changes to the tax system to alter the behaviour of companies and consumers to become more sustainable.

Sequels to Blue Planet II are unlikely to show the oceans looking any cleaner. Plastic pollution is a growing problem that will get worse before it gets better and consumer concern and the political response are likely to ratchet-up significantly. Green is the new blue or new red, depending on the party, but it is a vote winner for governments to take more action, not less.

Consumer behavior

While governments’ strategies are focused on Rethink, Regulate and Recycle, consumer behaviour is edging towards Re-use, Replace and Reduce. Re-use of carrier bags has become second nature since the plastic bag tax was introduced. With coffee cups, straws, cutlery or bottles, an increasing number of consumers are replacing single use disposable items with permanent or biodegradable ones. Deposit Return Systems (DRS) offer an incentive to recycle by adding a modest tax at the point of sale that is returned in exchange for the empty container. Glass bottle, can and more recently plastic deposit schemes are used in many places, including some US states, Germany, Norway and parts of Australia. Norway now recycles over 90% of its plastic bottles and other recyclable packages. In Haiti an innovative charity, The

Plastic Bank, is paying collectors for picking up discarded bottles for recycling (the collection centres are called Ramase Lajan which means "picking up money" in Haitian Creole). The founder, David Katz, calls this ‘social plastic’.

DRS could be a very powerful incentive mechanism to clean-up plastic waste but it requires a major adjustment in the price difference between virgin plastic and the recycled commodity. And there will be other consequences: a higher price on the raw material and a deposit on the container will raise prices on products delivered in plastic and reduce their demand.

Companies’ response

Companies face a dilemma in trying to be more sustainable without suffering a significant drop in demand. FMCG companies (fast moving consumer goods e.g Nestle, Unilever, Coca-Cola, Kraft Heinz, Proctor & Gamble etc), supermarkets and others have had decades to profit from the unhindered sale of goods in sell-and-forget plastic containers, and major changes in consumer behaviour on packaging will come as a shock. Plastic packaging has been a boon to margins - it has allowed products to be ‘premiumised’ with presentation and variable container sizes that allow smaller packs to be sold at higher prices per unit of volume. Consumers have been happy to pay much more for convenience, for instance ready-washed vegetables in a wrapped plastic tray are preferable to the muddy ones put in a paper bag by the greengrocer.

Manufacturers are now aiming to redesign plastic containers to make recycling easier and minimise reduction in sales. Unilever is among the most serious about sustainability and aims to make all its plastic packaging reusable, recyclable or compostable by 2025. Coca-Cola has a "bold new sustainable packaging vision" and is now committed to a target of 50% recycled content in all countries by 2030. It has also pledged to collect and recycle a bottle or can for every one it sells globally by 2030. Evian (owned by Danone) plan to create plastic bottles using 100% recycled content by 2025.

Note the emphasis in each strategy on retaining the current packaging system but adjusting it to recycled plastic. This is the least disruptive to the current business models but crucially may only slow the leakage of plastic into the environment. It faces significant practical challenges in being able to collect enough volume of reliable materials to recycle with constant quality specifications. This is particularly the case in emerging markets where there is insufficient government resource to arrange collection of post-consumer waste. Cynical observers suggest that if targets are missed it will be easy to blame contamination in the waste collection system or other factors outside the companies’ control.

But the key question is whether companies should produce and sell plastic-packed products in volumes that greatly exceed the capability of the local waste disposal systems to handle them. If governments are serious about plastic pollution, it is not impossible to imagine bans or volume restrictions being introduced, with severe consequences for future FMCG sales.

As an indicator of the seriousness with which some states are taking plastic pollution, in June 2018 single-use or disposable plastic was banned in Maharashtra state in India (including the city of Mumbai). The ban includes shopping bags, plastic cutlery and PET bottles. Offenders found using them face penalties of up to 25,000 rupees (£278) and three months in jail (McDonald’s and Starbucks have already been fined).

The next few years will see a major change in plastics use and the debate is likely to extend beyond packaging to the other major sources of plastic waste, including building, automotive and electronics, to ensure this material never ends up as waste in the first place.

The final word should go to Ellen MacArthur, whose foundation is doing so much to champion the circular economy: "Looking beyond the current take-make-dispose extractive industrial model, a circular economy aims to redefine growth, focusing on positive society-wide benefits. It entails gradually decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources, and designing waste out of the system".