Glass half-full or half-empty

As the “me too” movement continues to detail the almost routine harassment of and discrimination against women, we consider how effective investors have been in addressing issues of diversity and inclusion.

Despite a perhaps predictable focus on the economic imperative to act, progress is not happening fast enough. Shareholders need to be more forceful in promoting inclusive company cultures and leadership.

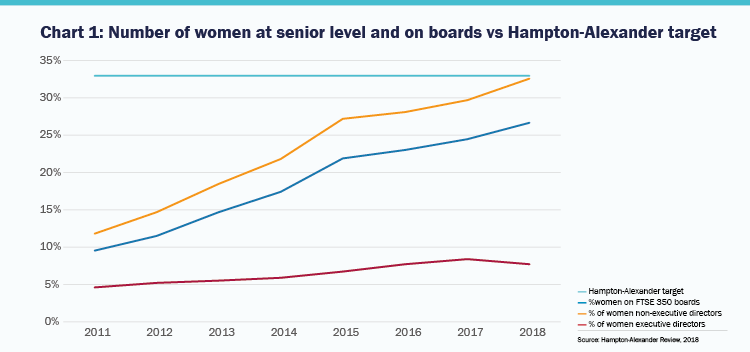

Investor concern regarding the lack of diversity in company leadership was spurred by a UK Government review, led by Lord Davies in 2011, which recommended that 25% of board members in the FTSE 100 should be women by 2015, and that the remaining companies in the FTSE 350 should set targets to address their deficits. Strong progress saw the FTSE 100 reach this target and the number of the all-male boards in the FTSE 350 fall from 152 to 15.

Picking up the baton since 2016, the Hampton-Alexander Review set a target for 33% of FTSE 350 boards, executive committees and their direct reports to be female by 2020. The proportion of female non-executives across the FTSE 350 has held up since then, reaching almost 33% by the last Hampton-Alexander count in November 2018.

However, this progress belies a much different trajectory at the executive level. Here, both the number and percentage of women have remained almost static.

The proportion of female executive directors across the FTSE 350 remains staggeringly low at 7.8%, and on some measures their status has actually worsened: the number of female CEOs has fallen 20% in the seven years since Lord Davies published his first report in 2011.1 This is enough to negate the gains made among non-executives, and it seems unlikely that the target of 33% representation will be achieved by 2020. Why might this be and how should investors respond?

Investors say they are committed

On the face of it, this is not the result of shareholder apathy or resistance. Investors managing around £11 trillion in assets, including Sarasin & Partners, have backed the 30% Club, which seeks a minimum 30% female representation on FTSE 350 boards by 2020, and at senior management level in the FTSE 100. The Group shares a belief that gender diversity contributes to “better leadership and governance, […] and ultimately increased corporate performance”.2

Indeed, at Sarasin & Partners, we challenge companies to address the underrepresentation of women on their boards. We vote against the Chairmen of all-male boards globally, and the Chairs of US and UK boards which do not have at least 25% female directors, unless their intention to rectify this is clear and convincing. And this approach has had an impact. Among the companies that we invest in, for example, a FTSE 250 firm recently appointed its only female non-executive director and committed to responding to the Hampton-Alexander Review following our exchange of letters with its Chair. Two female non-executives were also appointed at one of our Swiss holdings in December, after we had complained about the all-male board in a meeting with executives.

And directors are convinced

Nor would it appear that board members themselves are resistant to change. For example, 84% of US board members surveyed by PwC believed that greater gender diversity led to enhanced board performance, and 72% that it contributed to better company performance overall.3

A plethora of studies has sought to substantiate these beliefs by associating greater gender diversity with higher risk-adjusted returns. MSCI claims that “adding any number of female directors was correlated with higher median increases in EPS [earnings per share] compared to losing women from the board during the same period”.4 Credit Suisse analysed the performance of over 3,000 companies and found that those with at least one female director had generated excess compound returns of 3.5% per annum since 2005, compared to those with none. Outperformance was more likely as the number of female directors increased.5

So why hasn’t there been more progress?

It seems that knowing something is good for you does not necessarily lead to different behaviour. Change requires a push as well as the pull of economic outperformance. Regardless, we should not require a business case to dismantle entrenched barriers to inclusion of underrepresented groups. There has been no call for similar studies into the value added by men called David, for instance, who hold as many CEO roles as women do in the FTSE 100.6

What next?

Investors have a critical role to play in driving diversity. High-level commitments must be backed by proactive engagement and voting, and symbolic progress among non-executives matched within management teams and across business’ wider workforce.

As shareholders, we will continue communicating to companies that this is a priority, in discussion with boards and by taking voting action where there are no clear commitments to change. While pushing laggards to meet the 33% target by 2020, we believe that parity should be the ultimate objective. PwC also heard that almost half of directors thought their company was doing only a fair or even poor job of developing diverse executive talent, so we must understand and engage with the underlying causes of persistent inequality, which McKinsey calls the “uneven playing field”.7 Data provided by the Workforce Disclosure Initiative, of which we are a supporter, will allow us to have more meaningful discussions with companies about their employees.

McKinsey also notes that “women of colour and lesbian women face even more biases and barriers to advancement”, highlighting the intersectional nature of diversity which investors have perhaps been slow to recognise. Despite a 2016 review by Sir John Parker highlighting that the “boardrooms of Britain’s leading public companies do not reflect the ethnic diversity of either the UK or the stakeholders that they seek to engage and represent”, almost half of FTSE 100 companies still do not have a single non-white board or executive committee member.8 If shareholders truly care about diversity and inclusion in the companies they invest in, they must be prepared to act on this conviction through more forceful engagement and votes.

1 Hampton-Alexander Review, Third report, November 2018

2 https://30percentclub.org/about/who-we-are

3 PwC 2018 Annual Corporate Directors Survey

4 MSCI, the Tipping Point: Women on Boards and Financial Performance, December 2016

5 The CS Gender 3000: The Reward for Change, September 2016

6 CIPD and High Pay Centre, Executive Pay: Review of FTSE 100 Executive Pay, August 2018

7 McKinsey, Women in the Workplace, November 2018

8 A Report into the Ethnic Diversity of UK Boards, November 2016