‘Make America great again’ has unfortunately not proved to be quite so ‘Great’ for the seven billion or so of the world’s population that are not living in the USA. Massive tax cuts late in the business cycle, deregulation and an aggressive trade agenda (‘Trumponomics’) have clearly been rocket fuel for the US economy, but have left a troubling backwash for the rest of us. The sharp rise in the US dollar, higher oil prices (in part due to US-Iranian sanctions) and higher US interest rates have caused real damage in the emerging economies, while the scope and sheer uncertainty of the White House trade agenda have hurt business sentiment in almost every non-US economy.

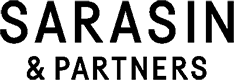

The result, intended or not, is that the US is likely to be the only major economy that will see growth accelerate at a faster rate in 2018 than in 2017 (chart 1). Yes, overall global growth continues to climb and the synchronised recovery we saluted little less than a year ago is still intact (the IMF projects world growth at 3.9%* this year and next, the strongest rate since 2010/11), but it looks decidedly less balanced. So far, the US and its financial markets are clearly the winners... but will this remain the case?

Emerging economies have borne the brunt of the damage

Emerging economies have borne the brunt of Trump’s trade policies and are naturally more vulnerable to a stronger dollar and the rising oil prices that typically come with sharply accelerating US growth. While Iran, Turkey and Russia are at the apex of US sanctions, the cooling momentum in the Chinese economy is of particular note. Beijing was already attempting to rein in risky domestic lending when confronted by an asymmetric trade battle with the US (where ‘China hawks’ in the White House, led by Peter Navarro, appear to have the upper hand). As the US mid-term elections approach there are few votes to be had from making concessions to China, suggesting that last week’s ‘talks about talks’ between a Chinese vice-minister and a US under-secretary offer little chance of a breakthrough. More likely is that President Trump will again up the ante and see if Beijing blinks, while domestic Chinese policy is already ‘reverting to type’ with increased spending on construction and an easing of lending standards designed to stabilise domestic growth. Both add unwanted financial risk to an already debt-heavy Chinese economy.

Before we become too gloomy, we must note this week’s good news on Mexican-US trade negotiations, even if what we see today is only a ‘partial deal’ designed in part to pressure Canada. It does show that the Trump White House can move rapidly to seal deals if it wants a political ‘win’, but this appears to be done largely to suit a US political timetable (specifically in the run-up to the mid-term elections on 7 November) rather than because of any deep-seated commitment to free-trade.

Europe’s self-inflicted wounds have amplified the damage caused by US policy…

One of the surprises of 2018 has been the comparative weakness of European economic data (both ‘hard data’ and business surveys). Europe, despite its very large trade surplus, is currently among the regions least impacted by US sanctions, with implementation of tariffs by the US on hold after the meeting between Juncker and Trump in July. While some blame can be laid at the door of US policy, Europe’s internal challenges have certainly amplified the impact. First, the probability of a messy ‘hard Brexit’ has risen, with a perilous political approval process for any deal likely on both sides of the Channel. Second, the demand for greater budget flexibility from Italian populists (a challenge that has long worried us) threatens European budget harmony and ultimately foreign holders of Italian debt.

Finally, ‘financial fragmentation’ is back with a vengeance in the eurozone – interest rates in ‘peripheral’ Europe are again meaningfully higher than in the ‘core.’ The ECB’s QE program has left German banks in particular drowning in reserves, whilst banks in the periphery, above all in Italy and Spain, face a shortage. This deficit is reflected in the need for the Bundesbank to effectively lend billions of euros of base money to the Banca d’Italia and Banco de España (reflected in the notorious “TARGET2 imbalances”). In other words, there are still regional fault lines and worrying feedback loops in the eurozone financial systems – which stand in sharp contrast to the unilateral America First policy emanating from the White House.

Is ‘Trumponomics’ really sustainable?

America First (including tax reform) has been more successful at lifting economic growth than many dared expect and momentum remains strong, with US consumer confidence running at an 18-year high. But can this continue at the expense of the rest of the global economy? And are US economic and trade policies really sustainable over the longer term? We see three primary risks for the White House:

- All the positive work done on the trade negotiations in terms of narrowing the US deficit could yet be unwound by further rises in the dollar - a currency war (in addition to a trade war) with China and the eurozone then becomes a material risk

- The US bond market finally takes fright at the explosion of Treasury issuance required to fund the swelling US budget deficit (the Congressional Budget Office currently forecasts that the deficit will widen from $800bn in 2018 to over $1.1trn in 2021). The sell-off would be exacerbated by the Federal Reserve’s concurrent reduction of its mountain of Treasury holdings, which began at the end of 2017 and is likely to continue until at least late 2019.

- US equity valuations correct as a combination of a strong dollar, rising interest rates and trade restrictions crimp next year’s earnings projections. The market correction is amplified by an increase in the President’s legal woes (all the more so if the Democrats re-take the House of Representatives in the November mid-term elections)

This makes us reluctant to fully embrace an America First investment strategy despite the strong momentum in markets in favour of the US dollar and US equities.

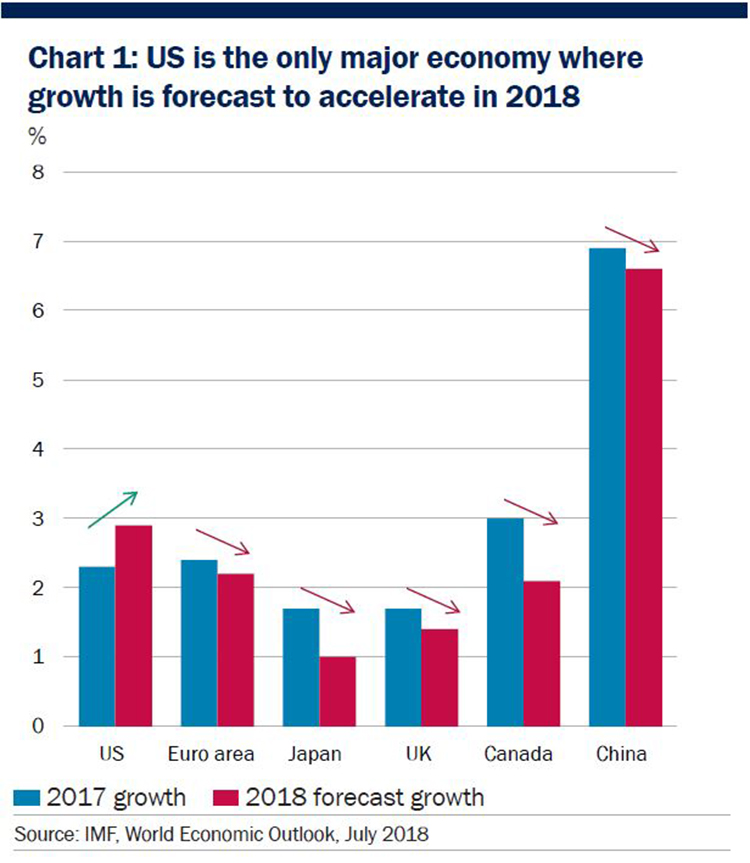

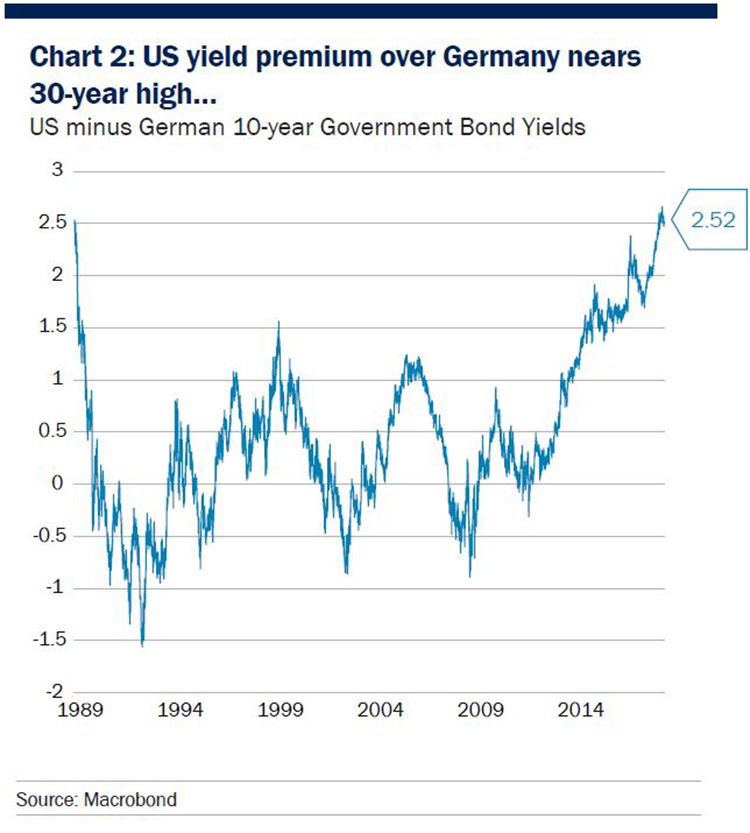

First, we see excessive divergence in developed world bond markets – the US-German 10-year bond spread is close to 30-year wides (chart 2). US high yield bonds are trading at the same spread as dollar-denominated emerging market (EM) debt, which is almost unprecedented (chart 3). Yes, economic and diplomatic risks certainly remain high for Turkey, but note that none of the other bellwether emerging markets (Mexico, South Africa, Brazil, etc.) are running the same dangerous mix of loose fiscal and monetary policy, hence direct contagion risk appears low. The major EM economies are in far better shape than in previous episodes of market stress (most recently the ‘taper tantrum’ of 2013).

Second, while America First policies have dramatically lifted US profits through a combination of corporate tax cuts and faster economic growth (S&P 500 earnings are expected to rise by an extraordinary 27% year-on-year in Q2 2018, according to Bloomberg), a large portion of this upsurge is undoubtedly now reflected in US equity market valuations. The S&P 500 index is trading at around 20 times historic earnings versus less than 14 times for Europe. Incorporating the anticipated uplift in US corporate profits one year ahead, the US multiple falls to 16.0, which still represents a 15% valuation premium over Europe even if we assume no European earnings growth. Interestingly, leadership in the US market is also evolving, with more defensive sectors, like pharmaceuticals and healthcare, outpacing technology over the last quarter.

Third, the question for investors, as ever, is how much of the Trump agenda is already reflected in markets? Over the past 12 months, US equities have outperformed the rest of world by 15%, the trade-weighted dollar has climbed by 5.5%, while the spread between US and German 10-year bond yields has widened by 70 basis points.

So how should investors react?

For global equity investors, there are clearly risks to Trumponomics, but the sheer strength of US profit (and top-line) growth suggests we should not be cutting positions wholesale just yet. Yes, at current valuations, compelling individual opportunities are appearing in Europe and potentially Japan – we would be adding, but gradually, on a stock-by-stock basis. For lower risk multi-asset and higher income mandates, we would look to add selected positions in US defensive equities. Ageing and dietary trends, for example, offer thematic opportunities in still cheaply priced US pharmaceuticals and consumer staples, while US banks continue to offer an unprecedented capital return story while acting as a useful hedge against interest rate risks. We have also taken advantage of low market volatility to add a layer of ‘equity portfolio protection’ across our balanced accounts.

For currency investors, we still see an opportunity for euro appreciation despite this year’s comparative weakness and Europe’s uniquely home-grown problems. Why? Because for Trumponomics to work, the US administration must ultimately seek to cap the dollar’s rise. With the eurozone running the largest current account balance in its history, the next phase of US policy could be to demand a stronger euro. President Trump has already accused China and the eurozone of currency manipulation via Twitter. The semi-annual US Treasury report due in mid-October may well formalise the administration’s antipathy to weakness in the currencies of its major trading partners.

Finally, our hunch is that President Trump is at heart a deal maker (as we are now seeing with Nafta 2.0) and if trade tensions are ultimately resolved, albeit on US terms, then the gap in investment performance between the US and the rest of the world will likely narrow. Under this scenario, selected higher-quality emerging market assets offer compelling value for a long-term investor. The exception, for a while at least, may be China, where White House policy appears to be more antagonistic and less open to constructive negotiations. We would, therefore, be comparatively cautious on Chinese economic risk and sceptical as to the ultimate effectiveness of their current stimulus plan.