While US financial dominance persists for now, the geopolitical landscape is shifting toward a multipolar world, a theme that will increasingly influence global investment over time.

Can global markets continue to thrive amid today’s growing geopolitical turmoil?

Despite a formidable list of geopolitical concerns, asset markets were surprisingly resilient in the third quarter. Global bonds, equities, and commodities all posted positive returns, while equity volatility ended the month near the quarter’s lows. True, the so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’ – Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Nvidia, Meta, and Tesla – and other technology stocks plunged sharply in August, but they recovered most of their losses by the end of September. Encouragingly, market leadership broadened, with utilities, real estate, and other interest-rate-sensitive sectors leading the rally.

How can investors reconcile this seemingly benign market backdrop with the most divisive US election in a generation, and devastating wars in Ukraine and the Middle East that are likely still escalating? Indeed, aside from a modest rise in oil prices in the first week of October, spurred by Iran’s massive rocket barrage, markets appear to want to overlook these geopolitical dangers once again. How much longer can this disconnect persist?

Investors are choosing economics over politics

Far from weakening in the face of global challenges, recent data suggests that the US economy is simply refusing to slow down. A scorching September jobs report followed strong readings from the Institute for Supply Management (ISM), which showed the US services sector expanding at its fastest pace since February 2003. The reading of 54.9 (with any figure above 50 indicating expansion) markedly exceeded expectations[1]. Moreover, upward revisions to US Q2 GDP revealed both stronger-than-expected growth in disposable income and a higher savings ratio. Some commentators are beginning to ask whether the US economy, far from slowing, might in fact be re-accelerating.

Globally, the counterweight to the US’s economic momentum has been the deflationary forces stemming from China’s deepening real estate crisis. Earlier this month, Chinese authorities finally acknowledged the risks and responded by loosening policy on three fronts: cutting interest rates and bank lending ratios, issuing loans to support stock buybacks, and promising fiscal stimulus – though the details of the latter remain unclear.

We estimate that this fiscal programme could amount to around 1.5% of GDP. While significant, it is a far cry from the 27% of GDP stimulus China unleashed in the two years following the global financial crisis in 2008[2]. Nonetheless, the mere recognition by the Chinese government of the need for stimulus remains a powerful tailwind for global growth.

Inflation: mostly surprising on the downside

Amid improving global growth, inflation continues to retreat. In the US, the core PCE deflator, the Federal Reserve’s preferred gauge, showed prices rising at 2.7% in the year to August, down from a peak of 5.6% in early 2022[3]. In Europe, headline inflation is falling particularly sharply – French headline CPI stands at just 1.5%, while Germany’s rate has slowed to 1.6%. Risks remain, of course: service sector inflation is proving sticky in Europe, while housing costs in the US remain elevated. But overall, the trend suggests a steady return towards central bank targets.

This easing of inflation is providing central banks with greater room to manoeuvre. In the past three months, market expectations for US interest rates at the end of 2025 have fallen from 3.9% to 2.9%[4]. With this backdrop, investors are probably right to believe that if growth does stumble central bankers will effectively ‘have their backs’.

Magnificent earnings from the 'Magnificent Seven'

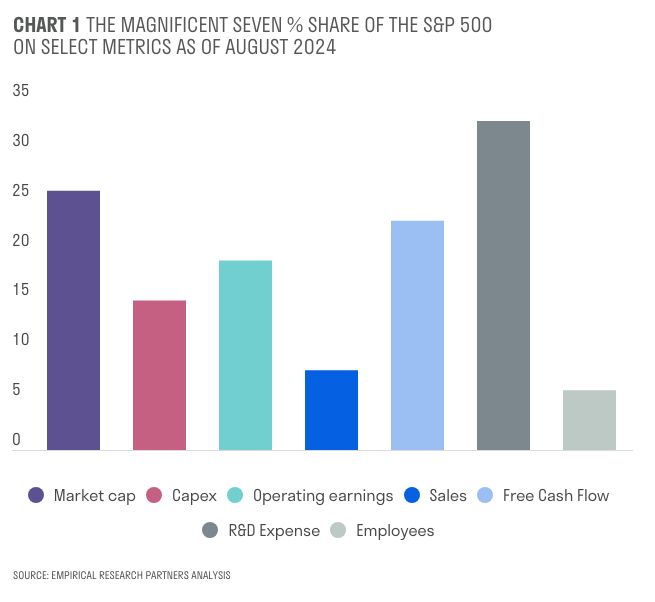

A third pillar of market resilience has been the robust earnings and cash flows generated by AI-linked technology giants, particularly the ‘Magnificent Seven (MAG7).’ In late July, concerns about the sustainability of these firms’ massive capital spending on AI triggered a sell-off. An index of MAG7 stocks tumbled 17% from its peak in August, following an impressive 37% gain earlier in the year, while US equity volatility nearly quadrupled.

Yet, just six weeks later, these same stocks had clawed back roughly three-quarters of their losses, and volatility had eased. The rebound was driven by the realisation that, despite their towering valuations – MAG7 stocks now account for 28% of the S&P 500’s capitalisation – these companies deliver profits, cash flow, and R&D spending in nearly equal measure. Unlike the dot-com bubble of 1999-2002, today’s AI-linked stocks are underpinned by robust earnings and extraordinary cash flow.

Learning to live in a multipolar world

So yes, while global markets remain well supported by a likely soft-landing and strong corporate earnings, they still face a bewildering list of geopolitical challenges. Many of these arise, at least in part, from a shift toward a multipolar world and away from the US dominated model that has managed global conflicts over the last three decades. As my colleague, Dr. Subitha Subramaniam, argues in the next article, today’s geopolitical landscape is undergoing a profound transformation – US hegemony, which followed the Cold War, is giving way to a more fragmented multipolar world.

In this new world, the US cannot so easily control the global political narrative in the way we have grown to expect. The Biden administration, for example, has struggled to influence the war in the Middle East and, despite massive military aid, cannot decisively change the situation on the ground in Ukraine. Concerns are growing, too, that the US may struggle, in a future conflict, to deter a Chinese move to annex Taiwan. New alliances are forming and military capabilities are growing outside of NATO, while a strong group of non-aligned nations is forming.

The US will remain a financial superpower for a while yet

While the geopolitical world is increasingly multipolar, the financial world remains, for the moment, largely unipolar. US equities, for example, account for 63% of the MSCI All Country World Index[5], compared to the US’s share of global GDP, which sits at around 26%[6]. In technology, US companies today comprise an extraordinary 90%[7] of the MSCI World IT Index. Only two non-US companies – ASML and SAP – make the top 10, and the largest of these is little more than a quarter the market capitalisation of Apple.

The US dollar, too, remains dominant. According to the Bank for International Settlements’ 2024 FX survey, the dollar was on one side of 88% of all currency trades[8]. So yes, we see the move toward a multipolar world as offering extraordinary investment opportunities but, for the present, it is US that still determines the direction of global financial markets.

Looked at from this perspective it is easier to understand why investors are comparatively sanguine today. They see a US soft landing, a low risk of recession, inflation rates that are falling and corporate earnings that are climbing, with dovish central bankers ready to step in as needed.

Oil and elections

However, two factors in particular, have historically had the power to derail US markets. The first is oil. In past Middle Eastern conflicts, energy prices were the primary transmission mechanism to the West. Today, crude prices (Brent) have risen by around 8% since the Iranian missile attack, but still remain broadly flat for the year. Why? The US has been the world’s largest oil producer since 2018, mitigating supply concerns. Moreover, OPEC still sits on 3-4 million barrels per day of spare capacity, about 6% of global consumption. Even if Iran were to disrupt traffic through the Strait of Hormuz, supply appears secure for now.

The second challenge is, of course, the US election, with polls in swing states too close to call. A Trump victory would likely bring a tax-cutting, pro-business agenda but also significant uncertainty around trade and tariffs – though US assets would probably outperform. A Harris win would continue Biden’s high-spending, green-energy-focused approach, with a more globally oriented policy outlook. In either case, government spending would support the US economy. Yet neither candidate has addressed the ballooning budget deficit and, for now, foreign investors remain willing to fund it.

Investment implications

In conclusion, despite the enormity of today’s geopolitical challenges, we believe investors should maintain a pro-equity stance across portfolios. Within this, we advocate maintaining steady exposures to technology and AI-linked investments, where current valuations are still underpinned by strong industry fundamentals and growth prospects. US election risks remain and we are particularly mindful of the policy implications of a 'clean sweep' for either party (when the President’s party wins control of both the House and Senate). Where appropriate, deploying portfolio insurance on a portion of equity positions seems prudent.

In our bond holdings, we remain modestly underweight, favouring corporate issuers. Here, inflows are supported by the substantial surplus accruing to UK pension funds. Within alternatives, our preferred asset remains gold. This is both as a hedge against rising budget deficits and as a beneficiary of increased purchases by Asian and emerging-market central banks, which are keen to reduce direct exposure to the dollar.

We continue to view the UK as something of a political, safe haven. Yes, we need to wait for the Autumn Budget on 30 October to assess whether Chancellor Reeves’s growth agenda remains intact which, if confirmed, would warrant increasing allocations to sterling.

In summary, investors are likely to focus on the US and global economies over politics for a while longer. Together this supports a pro-equity stance despite a geopolitical backdrop of turmoil and the obvious human suffering. However, in the longer term, we are entering a multipolar world where US dominance can no longer be assumed – this shift will increasingly shape investment flows and is set to become a powerful investment theme in the months and years ahead.

[1] https://www.ismworld.org/supply-management-news-and-reports/reports/ism-report-on-business/services/september/

[2] https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2024/09/27/at-last-china-pulls-the-trigger-on-a-bold-stimulus-package

[3] https://www.bea.gov/news/2024/personal-income-and-outlays-august-2024

[4] https://www.reuters.com/markets/rates-bonds/fed-rate-cuts-will-not-be-deep-market-expects-says-blackrock-2024-09-16/

[5] https://www.msci.com/research-and-insights/visualizing-investment-data/acwi-imi-complete-geographic-breakdown

[6] https://www.visualcapitalist.com/ranked-the-top-6-economies-by-share-of-global-gdp-1980-2024/

[7] https://www.msci.com/www/index-factsheets/msci-world-information/09375822

[8] https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/internationaldevelopment/2024/02/29/long-read-the-beginning-of-the-end-for-the-us-dollars-global-dominance/

This document is intended for retail investors and/or private clients. You should not act or rely on this document but should contact your professional adviser.

This document has been issued by Sarasin & Partners LLP of Juxon House, 100 St Paul’s Churchyard, London, EC4M 8BU, a limited liability partnership registered in England and Wales with registered number OC329859, and which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority with firm reference number 475111.

This document has been prepared for marketing and information purposes only and is not a solicitation, or an offer to buy or sell any security. The information on which the material is based has been obtained in good faith, from sources that we believe to be reliable, but we have not independently verified such information and we make no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to its accuracy. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice.

This document should not be relied on for accounting, legal or tax advice, or investment recommendations. Reliance should not be placed on the views and information in this material when taking individual investment and/or strategic decisions.

The value of investments and any income derived from them can fall as well as rise and investors may not get back the amount originally invested. If investing in foreign currencies, the return in the investor’s reference currency may increase or decrease as a result of currency fluctuations. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results and may not be repeated. Forecasts are not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Neither Sarasin & Partners LLP nor any other member of the J. Safra Sarasin Holding Ltd group accepts any liability or responsibility whatsoever for any consequential loss of any kind arising out of the use of this document or any part of its contents. The use of this document should not be regarded as a substitute for the exercise by the recipient of their own judgement. Sarasin & Partners LLP and/or any person connected with it may act upon or make use of the material referred to herein and/or any of the information upon which it is based, prior to publication of this document.

Where the data in this document comes partially from third-party sources the accuracy, completeness or correctness of the information contained in this publication is not guaranteed, and third-party data is provided without any warranties of any kind. Sarasin & Partners LLP shall have no liability in connection with third-party data.

© 2024 Sarasin & Partners LLP – all rights reserved. This document can only be distributed or reproduced with permission from Sarasin & Partners LLP. Please contact [email protected].