If Louis Vuitton was a food company, it would be the second largest public food company in the world. It has virtually the same market capitalisation as Toyota, the world’s biggest auto manufacturer, and is over five times larger than Tesco. Louis Vuitton has brands in its portfolio dating from the 14th century which is the heritage that emerging wealth cannot replicate.

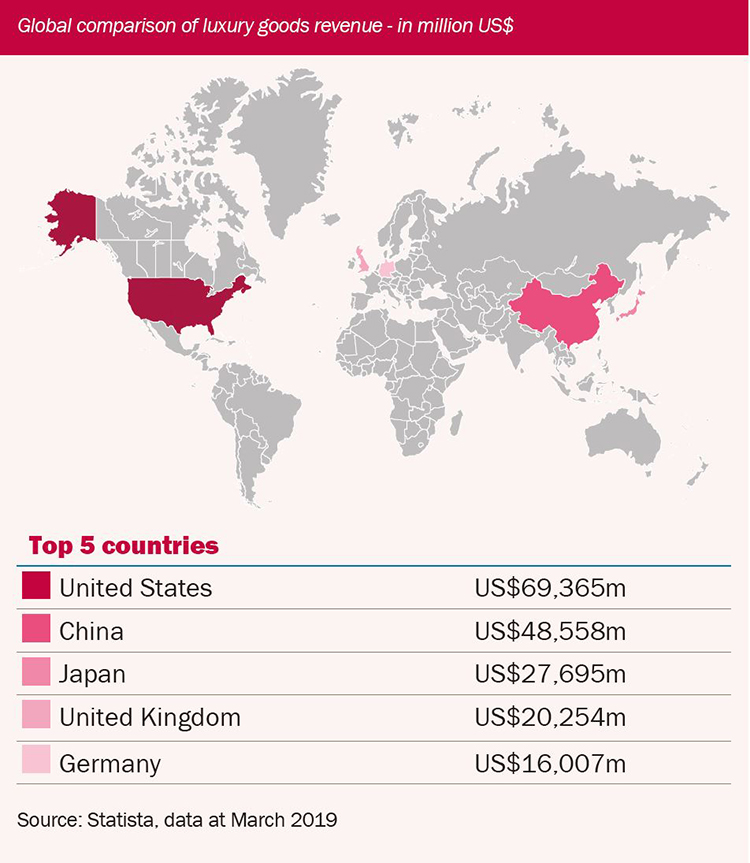

It is brands like Louis Vuitton that have proved so popular with the Chinese consumer. Although China’s GDP growth is slowing, China’s wealthiest people are growing richer more quickly: the growth rate of mainland Chinese with disposable incomes over $25k will grow approximately 10% per annum over the next few years. India, Indonesia and the Philippines will grow at an even faster pace. The premium and luxury goods market represents a particular sweet spot: cosmetics, skincare and luxury goods are the top three things “people like to buy when travelling abroad” according to a survey carried out in China. This is certainly reflected in commentary from the world’s prestige brand owners. Highly sought after labels include the Nike ‘swoosh’ logo, Marriott hotels, Nivea sun cream, Tumi suitcases (owned by Samsonite) Gucci clothing, a Swatch watch, Tiffany jewellery or perhaps a pair of Ray Ban sunglasses. Combine all of this with access to $50 smartphones and this leads to the real possibility of an Instagram generation not necessarily limited by age.

If we combine this trend with the typical millennial consumer, who is often stereotyped as vain, this opens up opportunities. Statistics reveal millennials have a higher propensity to indulge in luxury goods. Gucci recently announced that over 50% of its revenues comes from millennials, a large change from the previous decade. Perhaps the shift in attitudes to driving (the proportion of 17-20yr olds in the UK holding a driving licence has fallen by almost 40% in recent years) and car ownership have created more disposable income for this age group, often directed towards premium or luxury brands. With autonomous cars and a government determined to restrict car transportation on the horizon it is hard to see how this number will reverse its recent direction.

As wealth is created and habits emerge, the same stories tend to play out time and again. I grew up in an emergent Spain, relishing its freedom after decades of a socialist dictatorship, and witnessed first-hand how consumers respond to brands as they become available.

The consumer represents a significant portion of GDP (67% in the US in Q1 2019) and from the evidence we have seen, the propensity for emerging consumers to desire the lifestyles of their western counterparts puts us at a distinct advantage when analysing their behaviours.

Barriers to entry for brands in any industry are difficult to break down. You might manage to steal a drug formula but how can you replicate the terroir of an organically produced ‘champagne’?

Could it be argued today that certain luxury goods are the truest form of a ‘Veblen good’, where demand increases as prices do?

Brand and vanity are relatively insulated from technological disruption. Some would say made stronger as all this change forces a nostalgia for tradition and the analogue. This potentially gives investors access to strong management teams, superior company profitability, a predictably growing market and the ability to grow the capital base. It is the uniqueness of these dynamics that allows for these groups of companies to be consistently under-priced by the market and why we covet them as investment opportunities.