A synchronised global slowdown will likely test the limits of monetary stimulus and argues, in the longer term, for fiscal expansion. This has implications for investment strategy and global asset allocation…

2019 has dealt investors an unusual combination of outcomes; the politics have been explosive, the economics mildly negative, while the performance of financial markets has been extraordinarily robust. How is this possible?

The answer, it seems, is that we have entered a political version of a ‘Goldilocks Market,’ where policy and trade risks are large enough to spook central bankers into easing but the economic fallout is not yet serious enough to trigger recession. The result is ever lower bond yields (as I write around $14 trillion of which are trading with negative yields) but also continued growth in corporate profits and hence dividends. This has tended to drive yield-hungry investors into global equities, alternative assets and even gold (whose zero nominal yield looks comparatively attractive compared to European cash or bond yields). The result has been rises in almost every asset class in 2019, led by world equities, which, for a sterling-based global investor, have returned close to 20% in the year to 30 September.

Poor politicians and generous central bankers

So, can this rather precarious combination of poor politicians and generous central bankers continue and for how much longer? Let’s start with the politics, which to be frank look pretty awful. The China-US trade dispute is unresolved, US-Iranian relations have deteriorated to crisis point, a Brexit agreement remains elusive, while US presidential impeachment (only the fourth attempt in American history) is now openly discussed. Unsurprisingly, measures of trade and policy uncertainty are through the roof1 and yes, this is now clearly affecting business sentiment as we saw in last week’s ISM manufacturing survey. From a market perspective though, much is already discounted; almost everyone saw Brexit negotiations running to the wire, China-US tensions are structural and long-term, while the US and Iran have always had a difficult political history. Even the nascent impeachment hearings surprise few who have seen the operating style of the Trump White House – in short, it seems that markets are happy to discount the worst but then hope for something rather better.

There is an exception though – investors are not yet ready for a sharp policy shift to the Left, such as you might see from a Labour majority government in the UK, or say in a Warren or Sanders presidency in the US. In either instance there is the likelihood not just of higher taxes and increased fiscal spend (both are likely and to an extent may even be desirable) but also the risk of a much wider assault on corporate profitability and equity ownership which is not yet priced into markets.

The twilight of monetary policy

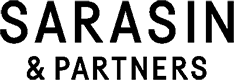

From an economic perspective, it is clear we are now entering a synchronised global slowdown, triggered in large part by political and trade uncertainty (chart 1). The OECD projects that the world economy will grow by just 2.9% in 2019, the weakest annual rate since the financial crisis more than a decade ago. Escalating trade conflicts are taking their toll on business confidence with the epicentre of the impact seen in the German export-led economy (German factory orders are down 6.7% year on year). But indicators do not yet suggest a global recession; employment is robust (US unemployment hit a 50-year low of 3.5%) while the service sector has so far suffered only modest ‘collateral’ damage – most importantly, in almost all major economies, real wages are growing strongly. So how will central bankers respond?

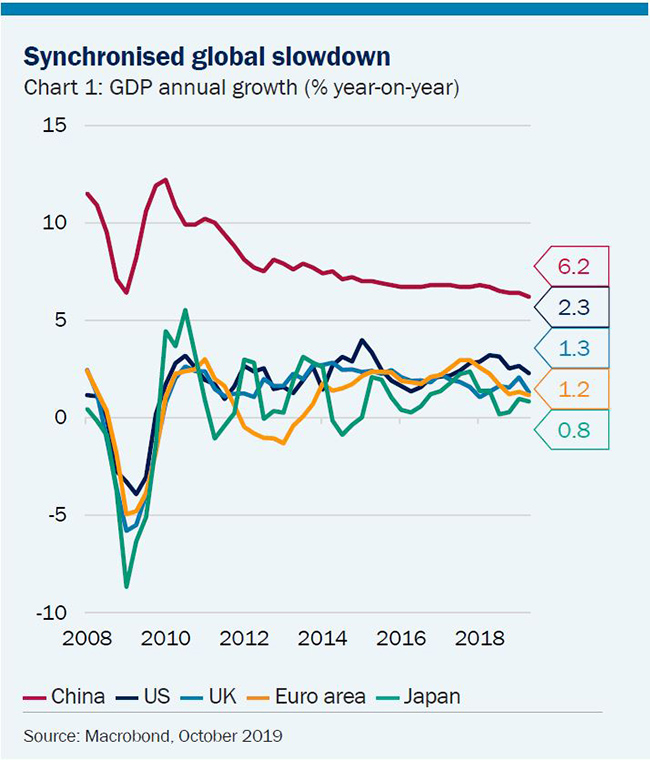

We are currently assuming a further three rate cuts of a quarter of a percentage point in the US over this year and next. We also see a continuation of the ECB’s bond buying programme and potentially interest rate cuts in the UK on anything, but the most optimistic, Brexit outcome. In the longer term though we are entering the twilight of big policy easing because of growing political resistance in Europe and a reluctance to embrace zero bound rates in the US (chart 2). This sets the stage for a further global pivot from monetary to fiscal policy – with budget deficits set to rise in the US, UK, China and ultimately Europe (expect Germany’s balanced budget mantra to crumble).

In the immediate future, this argues for lower rates and hence more flows into equity assets. However, over the longer term, if fiscal policy takes up the running then the outlook for asset markets is more ambiguous. Expect more infrastructure spend around climate and alternative energy, greater focus on supporting lower income wage growth and renewed home-building projects to mitigate rent increases. These are all trends that offer potential investment returns but carry with them the risk of substantially higher government borrowing. If growth is already weak then this need not lift bond yields, although countries that are more indebted could be vulnerable to volatile investor flows and potentially weaker currencies.

What are the implications for investment strategy?

So how should investors respond to a world economy that is slowing, where political uncertainty is high and where generous monetary policy is steadily giving way to fiscal stimulus?

- A synchronised slowdown across global economies argues for a thematic focus in equity portfolios targeting areas of longer-term structural growth. We continue to focus our equity selection on the beneficiaries of powerful long-trends: automation and digitalisation, ageing, evolving consumption and climate change.

- Equity dividend yields continue to offer a near record yield premium to government bonds in every major market (including the US if one allows for share buy-backs). Underlying global dividend growth was a robust 4.6% year-on-year, with Japan, Canada, France and Indonesia breaking all-time records2. Certainly caution is needed with higher yielding equities in older (often climate-challenged) industries, but a thematically focused dividend portfolio with a strong stewardship culture and climate awareness remains a compelling asset class.

- With nominal bond yields far below inflation across the UK and Europe, holding equities with associated portfolio insurance can be an alternative to traditional fixed interest portfolios.

- Gold continues to benefit from central bank buying and healthy ETF flows, supported by negative real interest rates across Europe and Japan. In the longer term, gold provides a useful hedge against a renewed build-up of government debt and ultimately any structural weakness in the US dollar.

- The political risk around Brexit and a no-deal scenario is extreme in the short term. Investors should retain higher than normal cash balances, focus on liquidity in their asset selection and emphasise quality and balance sheet strength in their UK equity and bond holdings. Our focus on global equities and cross-border thematic trends should also help to insulate portfolios from excessive UK-centred risks.

2019 has already rewarded investors with robust returns across an unusually wide range of asset classes. As the global economy slows and policy makers embrace fiscal rather than monetary solutions, this broad-based market rally will likely narrow. Focusing on companies supported by powerful thematic drivers, a strong stewardship culture and heightened climate awareness will be core to a successful investment strategy in 2020.

1 Global Economic Policy Uncertainty Index - Bloomberg

2 Janus Henderson Global Dividend Index - August 2019