As an increasing number of charities seek to invest more responsibly and address environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues within their endowment portfolios, it seems right to ask if they are getting what they want from the asset management industry.

What are the good and bad practices when it comes to the ‘stewardship’ of client assets? How can a charity identify ‘greenwashing’ (a term coined by environmentalist Jay Westerveld in 1986 to describe misleading corporate environmental claims)? Asset managers have to step up their reporting of ESG issues, particularly around climate change, and clients need to hold their asset managers firmly to account.

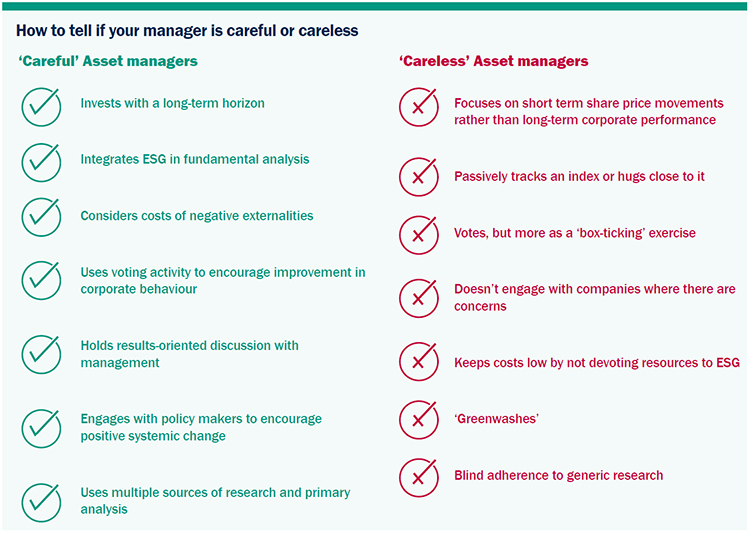

Careful versus careless

In the broadest sense, it is possible to distinguish the attributes of those managers one might describe as ‘careful’ from those who appear to be ‘careless’. A careful and responsible asset manager should think long term, consider the broader – and often complex – relations between society and a business and engage actively with companies to drive positive change. In contrast, the ‘careless’ brigade often over simplify to make their lives easier, spend little time and resource actively engaging and rarely consider the broader policy issues that may put their clients’ capital at risk. Above all, trustees need to beware of ‘greenwashing’ from managers who jump on the ESG bandwagon and make statements that may not stand up to scrutiny (see table below).

Beware also those that ‘outsource’ and rely on external agencies for their ESG work. The recent case of Nissan and the falsifying of emissions data at five of its plants, together with the arrest of its Chairman, Carlos Ghosn, on allegations of financial misconduct, highlights the issue. Until recently, Nissan was graded B on ESG factors by MSCI and only downgraded to their lowest score ‘CCC’ in September 2018, even though the governance failings have been evident for some time. Rather surprisingly, MSCI still grade Renault as an ‘A’, despite the very close links and cross-shareholdings between the companies. ESG issues should be a fundamental part of the risk and reward analysis of every company and there are very few alternatives to conducting high quality primary research.

Stewardship as a mindset

We believe that stewardship is a mindset, which means thinking like owners of a business, and not simply shareholders. A key element of active management is engagement. It is important to speak out as shareholders, both in relation to companies, but also as part of wider ‘policy work’, which will shape the investment landscape and help promote the sustainability of returns.

As companies grow, their influence over society spreads. Executives of the world’s biggest companies arguably exert more influence than the governments of many countries. One of the most controversial topics is executive pay and here, as in many areas, we find too few investment managers willing to stand up to the power of company boards. All too often, investors simply vote in line with management’s recommendations. The FT conducted a survey last year, which showed that the world’s largest fund managers voted in favour of pay awards more than 90% of the time. So far this year, Sarasin & Partners’ has voted against 42% of pay resolutions in the UK and 50% in the US.

However, wider issues should be taken into account

The issue is not limited to voting on Annual General Meeting resolutions. Asset managers should also address wider environmental and societal issues. No company is perfect and most have exposure to ‘negative externalities’, a term coined by economists to describe costs which are imposed on others without adequate compensation. This could be, for instance, harmful air or water emissions. Businesses that do this can be accused of exploiting ‘natural capital’ or exploiting ‘social capital’ in order to make ‘financial capital’.

Take the example of consumer company Coca-Cola, where obesity and plastic packaging are serious problems. The company clearly recognises these risks and discloses them in their annual ‘10K’ filing with US regulators: “obesity concerns may reduce demand for some of our products” and “changes in laws on beverage packaging could increase costs”. They are aware of these threats to their business and one could argue have responded by adjusting product lines with more diet variants and announcing a new global ambition to “collect and recycle a bottle or can for every one we sell by 2030”. They embrace the concept of the circular economy, where everything gets recycled instead of thrown away. The question is whether these companies are acting quickly or resolutely enough and whether their focus should be on reducing, as well as simply recycling, waste. Taking action faster will likely cut profits (and therefore management incentive payments), so the cynic would argue they are simply delaying action for as long as they are able. Ultimately, companies who do not consider their harmful externalities could see sales and profits suffer and share prices fall.

Climate change – our greatest challenge

The greatest environmental challenge and externality of them all, is climate change. The major governments of the world finally agreed some common targets at the UN Paris Summit in December 2015 with a pledge to “keep a global temperature rise well below 2oC and pursue efforts to limit even further to 1.50C”. Sadly, adding up the pledges made so far still results in more than a 3oC increase and many predictions suggest it could be even worse. The recently concluded UN COP24 climate talks in Katowice, Poland, which sought to negotiate a global framework and set of rules that would support the implementation of the 2015 Paris climate agreement, provide some cause for optimism, however. Despite a number of issues, and reluctance from some parties, a new ‘rulebook’ was agreed that will act as an operating manual for all 196 countries when they come to report on their progress over the coming years. It will also provide guidance on the relative roles of both developed and less developed nations in mitigating their emissions and participating fully in the Paris process.

Serious action is needed to radically transform the energy system by reducing our net emissions to zero. Policies to tackle climate change still need to ratchet-up dramatically and if action is not taken, then climate stabilisation will prove impossible and so will follow material physical, ecological, societal and economic costs. Accordingly, ‘Paris’ as a specific objective may not be met, but the eventual manifestation of climate related impacts will become so material, that a cut to emissions must inevitably follow. At such a point, the transition away from a carbon intense economy is likely to be disorderly from a macro-economic, societal and asset pricing perspective. Crucially, we do not believe investment markets are yet discounting the consequences of such possibilities adequately, if at all.

Time for everyone to take action

Everyone needs to play a part in driving change and that must include both asset owners and asset managers. At Sarasin & Partners, climate change is clearly identified as one of our five ‘mega-themes’, which will shape investment markets in the decade to come. An increasing number of our charity clients have signed up to our ‘Climate Active’ strategy, which combines engagement and divestment to persuade companies to take faster action where we identify climate risks. For these clients, we will divest from any company where we do not believe enough progress is being made. Many managers focus too narrowly just on fossil fuel companies, but it is a wider issue across the investment spectrum from ‘producers to users to consumers’ and affects many different businesses. So far, we have written to 35 companies seeking a commitment to the Paris goals and an alignment with a pathway towards zero net emissions. In our follow up conversations with companies, too often we are told that no other investor has asked this question.

This is not to say that other institutional investors are not active. Several are, and we form alliances with like-minded investors to increase the power of our voice wherever we can. For example, we are co-coordinators, alongside the Church Commissioners, of a large group of investor engagements with European oil and gas companies under the Climate Action 100+ initiative, which brings together over 300 investors and $32 trillion of invested assets. We are also leading an investor initiative to challenge companies and their auditors to ensure they are reporting to shareholders in a way that takes account of the Paris Climate Accord. All such efforts should be widely encouraged, while attempts at ‘greenwashing’ need to be robustly challenged.