Deng Xiaoping, the father of China’s economic transformation, said once “cross the river by feeling the stones”.

The phrase, now as popular as a Chinese proverb, encapsulates China’s economic philosophy over the past 40 years, describing how to navigate an inherently uncertain landscape cautiously, step-by-step, by feeling one’s way. Trade and opening up policies were at the heart of Deng’s early economic reforms from 1979, which helped transform China to the second largest economy in the world and the world’s largest exporter of goods.

Now, as a middle-income country re-balancing to broader sources of growth, and in the face of the global backlash against globalisation, China faces a critical juncture in its economic history. The key questions that arise are: how important is trade to China’s economic trajectory, and secondly, what will the future of China’s trade look like as it navigates the probable persistence in slower global trade.

Trade as an engine of China’s growth

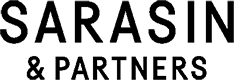

Since 1979 and the creation of special economic zones in China’s southern coastal regions, trade has formed a critical part of China’s economic success story. China has evolved from the world’s thirtieth largest trading country in 1977- on the eve of economic reforms - to surpass the US in 2009 to become the world’s largest trading nation. Nominal exports have grown at an annual average pace of 20 per cent during this post-liberalisation period, with membership to the World Trade Organisation in 2001 acting as a further catalyst for rapid trade expansion. Undoubtedly, China’s trade expansion and rapid economic growth have been closely aligned. China currently accounts for 13% of global merchandise exports, and 15% of the global economy in USD terms (chart 1).

Yet, estimating the contribution of exports to China’s growth is more complicated than it first appears due to China’s participation in vertically integrated global supply chains. Processing trade, especially prevalent in machinery and transport equipment goods, accounts for around one-third of China’s total trade. Furthermore, there are various transmission channels through which trade impacts an economy, including both direct effects from net exports, but also indirectly from the impact that trade has on spurring business investment, as well as the long run impacts of trade on total factor productivity by promoting domestic competition and enabling knowledge transfer from abroad.

During the height of China’s export boom – pre-2009 and the onset of the financial crisis - studies estimated that a 10% decrease in China’s export growth was associated with a 2.5 percentage point decline in GDP growth on average – with the secondary effects dominating due to the spill over effects from exports to domestic demand and employment.

The heightened level of trade tensions, notwithstanding the recent truce at the G20 in Osaka, raise questions over the outlook for China’s trade?

What will the future look like?

To provide an outlook for the external sector, it is important to note, firstly, that China’s explosive export growth over the past several decades was driven by a unique set of factors. In particular, the export and manufacturing sector benefited from abundant supplies of low-cost labour and the process of urbanisation, with around 20 million more people in urban areas per year in search of higher pay from the lower-paid agricultural sector. Artificially cheap inputs to production through government subsidies, such as tax rebates, discounted utility and land rentals and access to finance, were also hugely beneficial to exporters, as was a significantly undervalued exchange rate.

However, these benefits have now been either exhausted or are no longer applicable. The emergence of labour shortages and strong wage growth suggest that China has already reached the “Lewis turning point” –the inflection point where developing countries exhaust their supply of cheap rural labour. Additionally, due to criticisms by members of the WTO, China has been under pressure to reduce state subsidies to its exporters. As a result, China has lost some comparative advantage as an exporting nation. The real exchange rate, which can serve as a proxy for China’s real competitiveness vis-à-vis with the rest of the world has increased by almost 50% per cent since 2005 when the government allowed greater flexibility in the exchange rate.

Secondly, as China’s economy continues to grow richer, trade will continue to be a less critical driver of growth. As a share of GDP, exports currently account for around 18% of the economy, down from a high of 35.3% in 2004. Economic re-balancing away from trade and investment and towards domestic consumption will only drive this trend forward in the future. Consumption as a share of GDP will continue to rise, supported by urbanisation, rising middle class and population ageing.

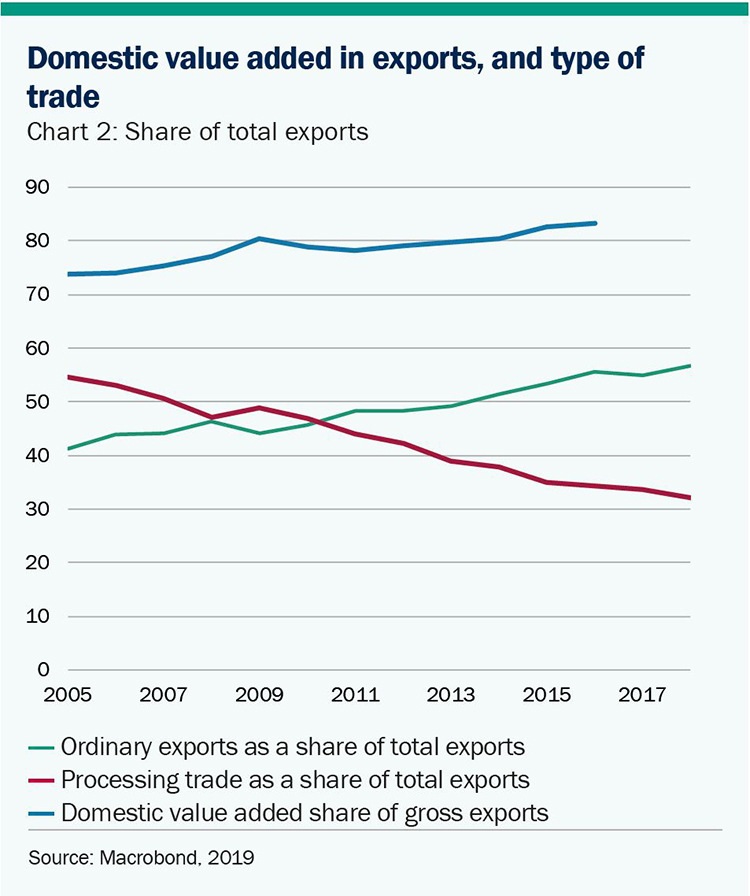

The third likely feature of China’s future trade is the change in its export mix and production away from labour-intensive manufactured goods towards more sophisticated higher-value added goods. The category machinery and transport equipment is a growing share of China’s total exports to around 50%, while total manufacturing goods are moving in an opposite direction falling to a total share of less than 40%. Similarly, there is increasing evidence of rising Chinese content in exports through on-shoring, with domestic value-added in exports rising steadily and the share of processing trade decreasing (chart 2). This trend of moving up the value chain is likely to continue, and possibly will be exacerbated by current trade tensions by encouraging China to look internally to satisfy its own import demands.

The fourth likely trend in China’s future trade is a growing trend towards emerging and developing economies. Given stronger population growth dynamics and productivity catch up, emerging and frontier markets are forecast to experience almost double the growth rate of advanced economies over the next decade. What’s more, China is set to be particularly positioned to benefit facilitated by the government’s Belt and Road Initiative, which aims to boost China’s trade and investment links with more than 80 countries along the ancient silk road. Merging trade and regional development certainly provides economic and political benefits for China, but it has also raised questions about China’s influence in the region and its rising leverage over smaller and more dependent economies.

What will this means for the rest of the world?

The changing nature of China’s external sector will inevitably cause spill overs for the rest of the world. As China’s cost of production continues to rise and regulatory catch up with advanced economies takes place, global supply chains will diversify, particularly benefiting countries with a skilled workforce, competitive labour costs, logistical support systems, and political stability.

This is especially true in the textile and apparel industry, whereby over the past decade corporates including Nike and Adidas have shifted their manufacturing base away from China to Vietnam and other low-cost countries. Escalation of US-China trade tensions will only intensify this shift away from China, and not only in the textile industry which typically bears the brunt of importing countries protectionist measures. Recently, Apple proposed to shift 15-30% of its production capacity from China to south-east Asian countries. With rising protectionist measures globally, supply chain security will be an additional driver influencing corporate decisions.

Furthermore, as China moves up the value chain, the degree of export competition between China and advanced economies will inevitably increase. In terms of nominal R&D spending, China is now the second largest spender after the US in purchasing power parity terms. The government’s “Made in China 2025” plan clearly sets out the country’s ambitions in driving technological innovation, with generous government policy support for the country to become global leaders in sectors including robotics, information technology and clean energy. The strategy, while criticized by the US and the west for creating an uneven playing field, could see some commoditisation of high-tech products, making products such as high-speed rail and autonomous driving more accessible and affordable, particularly by low-income countries.

However, it is not a corollary that greater investment in R&D will translate to a country’s ability to innovate and reduce reliance on foreign technology. Many challenges remain. The share of patent income to GDP remains low in China, and the legal protection of intellectual property needs to further improve. So while China has demonstrated rapid success in “catching up” and making incremental improvements in certain fields, innovation will be critical in the next phase of its economic development to escape the proverbial middle income trap.