Why politicians face unpopularity on climate change

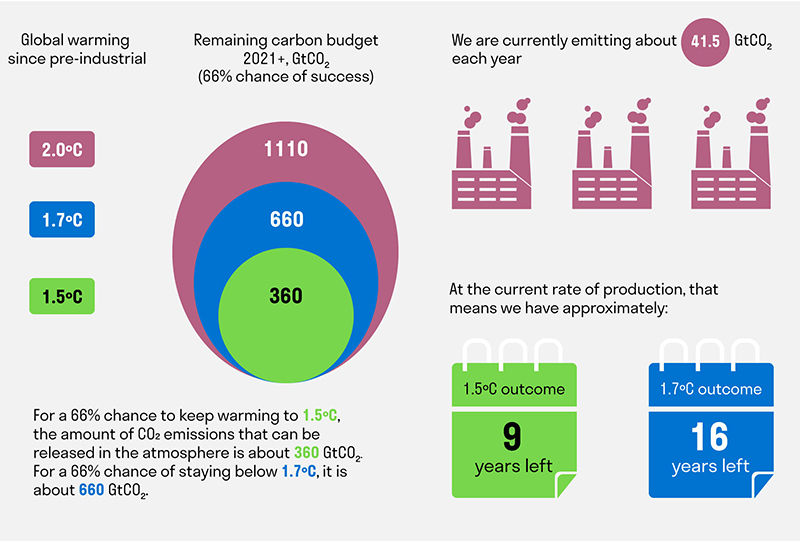

The 26th ‘conference of the parties’ (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) will take place in Glasgow in early November. As a gathering of all 197 countries in the world, it ‘aims to prevent dangerous human interference with the climate system’. “Code red for humanity” is how UN Secretary-General António Guterres described the scientific report prepared for leaders ahead of the conference. Can sufficient change be generated to cut emissions by the 45% required1 by 2030 to keep the temperature rise below 1.5°C and reduce the existential risk we all face?

The conference has four core objectives, the first of which is a credible finance package to help poorer countries. This is a make-or-break issue to retain trust in the negotiations. Developed countries have acknowledged that they are responsible for historical emissions and that emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) simply cannot afford to adapt to climate change, address loss and damage and leapfrog to low-carbon development pathways. In 2009, developed countries pledged to provide $100 billion each year to EMDEs by 2020. However, to date not all of that money has materialised.2 If EMDEs are unable to finance strong and sustainable recovery, it will not only be their populations that suffer but climate goals will be left irrecoverably beyond reach.

Achieving the second objective of ‘creating a collective commitment and road map to accelerate transition’ will require remarkable compromise. Each country is updating its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), reflecting its own climate plans and the 113 NDCs published to date are together projected3 to decrease greenhouse gas emissions by 12% in 2030 compared with 2010. However, this is way short of the IPCC estimate that a reduction of 45% in CO2 emissions is required by 2030 as a milestone to net zero by 2050. In Glasgow most countries will join one or more large negotiating groups. The EMDEs form the largest group, known as the Group of 77 (actually 134 countries, plus China). The G77 is pushing for additional loss and damage finance facilities for vulnerable developing countries. Reflecting differing perspectives, the Umbrella Group of high-emitting countries, including the United States, Russia, Canada and Australia are cautious about ambitious mitigation, while the Arab Group and other oil-producing countries point out the challenges of diversifying their carbon-intensive economies. The UK and EU’s emissions-cutting targets are among the most ambitious of the world’s major economies; even so, some EU member states are struggling to present a united negotiating position.

In Glasgow most countries will join one or more large negotiating groups. The EMDEs form the largest group, known as the Group of 77 (actually 134 countries, plus China). The G77 is pushing for additional loss and damage finance facilities for vulnerable developing countries. Reflecting differing perspectives, the Umbrella Group of high-emitting countries, including the United States, Russia, Canada and Australia are cautious about ambitious mitigation, while the Arab Group and other oil-producing countries point out the challenges of diversifying their carbon-intensive economies. The UK and EU’s emissions-cutting targets are among the most ambitious of the world’s major economies; even so, some EU member states are struggling to present a united negotiating position.

Another objective of the conference is “ambitious action on carbon pricing”. A carbon tax offers the most cost-effective lever to reduce carbon emissions at the scale and speed that is necessary. It will send a powerful price signal that harnesses the invisible hand of the marketplace to accelerate change. More than 3,600 US economists have called for a carbon tax but, reflecting the domestic political climate, the US is not likely to cooperate. Recently the White House has talked of “code red – the nation and the world are in peril” but also said that the President is “looking at every means we have to lower gas [petrol] prices. Achieving compromise at COP26 will be immensely challenging.

"Code red – the nation and the world are in peril"

A significant new objective is ‘protection and rebuilding of natural capital’. Overexploitation of natural resources for human use over the last 150 years has contributed significantly to changes in climate and the accelerating decline of biological diversity worldwide. 83% of wild mammal biomass has been lost and half the biomass of wild plants.4 So leaders are forced to confront a combination of factors that threaten human livelihoods, health and food security. This will be reflected in another conference in Kunming, China in late April 2022 - COP15 will aim to “bring about a transformation in society’s relationship with biodiversity”.

Good COP/ bad COP

Meeting the specific conference objectives will be very challenging, but even agreement on all of them would be a narrow definition of success. Accelerating the transition to net zero requires imposition of change on an extraordinary scale, much of which constrains consumption, interferes with existing individual freedoms and will be unpopular.

It is understandable that politicians have wanted to play ‘good cop’ rather than ‘bad cop’. But COP26 and COP15 aim to revolutionise many aspects of daily life: the transition to zero-carbon power and zero-carbon transportation; carbon pricing; sector policies; phaseout of coal; mobilisation of private businesses & finance; and reform of land-use and agriculture. To cut emissions by 45% in the eight years left before 2030 now requires radical new regulations and significant intervention in laissez-faire, profit-maximising markets.

These reforms will require a combination of ‘good cop’ and ‘bad cop’ coercive approaches to achieve sufficient changes in behaviour. Where to start? There are some ‘quick wins’: first, the IMF, the World Bank, and others have called for elimination of fossil-fuel subsidies (the International Energy Agency estimates that fossil-fuel-consumption subsidies amounted to just over $180 billion globally in 2020).5 And the IPBES has called for reform of agricultural and water subsidies. More than $1m per minute is still spent in global farm subsidies,6 driving the climate crisis and destruction of wildlife in support of high-emission cattle production, de-forestation and pollution from the overuse of fertiliser.

Secondly, companies can be encouraged much more forcefully to clean-up their act. There are some bad offenders: one study estimates that just 100 active fossil fuel producers are linked to the emission of 71% of global industrial greenhouse gases (GHGs) since 1988.7 But the offenders are not only giants like ExxonMobil, Saudi Aramco or Gazprom; most companies contribute to the planet’s problems in the process of earning their profits. Many face gradual tightening of regulations (for example the ban on the sale of internal combustion engine cars in the UK by 2040 has been shifted to 2030). And the legal claims against companies for their environmental damage are only just getting started.

Just 100 active fossil fuel producers are linked to the emission of 71% of global industrial greenhouse gases (GHGs) since 19887

There is often little public awareness of these impacts and they are mostly not disclosed in financial accounts. A remarkable number of companies claim to support combating climate change on the one hand whilst failing to acknowledge their risks from misalignment with decarbonisation on the other. The auditors who have a role in policing such accounting misstatements have been too quiet. Governments could do a lot to help speed up better recognition of climate change impacts and other ‘externalities’ in company accounts.

To that end, Sarasin & Partners recently led a large coalition of other asset managers and advisors in writing to Alok Sharma, president of the COP26 conference. We asked for heads of state to set a clear timeline for companies to produce accounts consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5°C above the pre-industrial level, and for auditors to call out where they don’t.

We all hope that COP26 will be reported as a ‘good COP’ but the risk that it underwhelms is high: the very short remaining time frames to keep temperature rise to below +1.5°C requires change on a scale sufficient to necessitate much greater coercion of consumers and companies to alter their behaviour.

It is natural for politicians to focus on short-term popularity and immediate national priorities rather than longer-term global threats. But there is now no excuse for subsidising more damage, for failing to engage consumers and companies more actively and for failing to enforce existing accounting, audit, legal and regulatory disciplines. The 'good cops' need to bring in some more straight-dealing cops to measure, regulate and ration natural capital resources and retain confidence in the COP processes of “preventing dangerous human interference with the climate system” and “bringing about a transformation in society’s relationship with biodiversity”.