A review of long-term oil price assumptions underpinning company balance sheets.

Why shareholders must be aware of the disconnect between oil company narratives and the numbers on their balance sheets.

With the Brent crude oil price having risen from roughly $50 per barrel over the last three years to nearer $75 today, oil and gas companies are reporting levels of profit and cash flow not seen since 2014. Shareholders are accordingly optimistic that dividends will grow.

But are company financial statements providing a reliable view of these businesses’ underlying economic strength, taking into account reductions in long-term demand for fossil fuels that were agreed under the 2015 Paris Climate Accord?

Based on a review of eight listed European companies’ financial statements, we believe they are not. Critically, commodity price assumptions that underpin company balance sheets appear to ignore global decarbonisation. Consequently, companies may be overstating their performance and capital. Furthermore, auditors are endorsing these accounts, and shareholders are approving them.

Of course we cannot know for sure what the future oil price will be. But oil and gas companies must identify a long-term price to use in their accounts. This underpins not just reported capital, but also profit and dividends. In Europe, accounts are required to be prudent to protect shareholder and creditor capital, thereby underpinning trust in financial markets.

So what assumptions are companies making?

The eight oil and gas companies (Royal Dutch Shell, BP, Total, Equinor, Eni, Repsol, Cairn Energy and Soco International) are assuming long-term oil prices of $70 to $80 per barrel from 2020/21 to generate their accounts, rising by 2% a year thereafter. This translates into a price of $127 to $145 by 2050.

The question is whether this is prudent in a world that is accelerating the phase out of fossil fuels.

A number of external benchmarks suggest $70 to $80 is not sufficiently conservative, and that consequently companies may be overstating their positions.

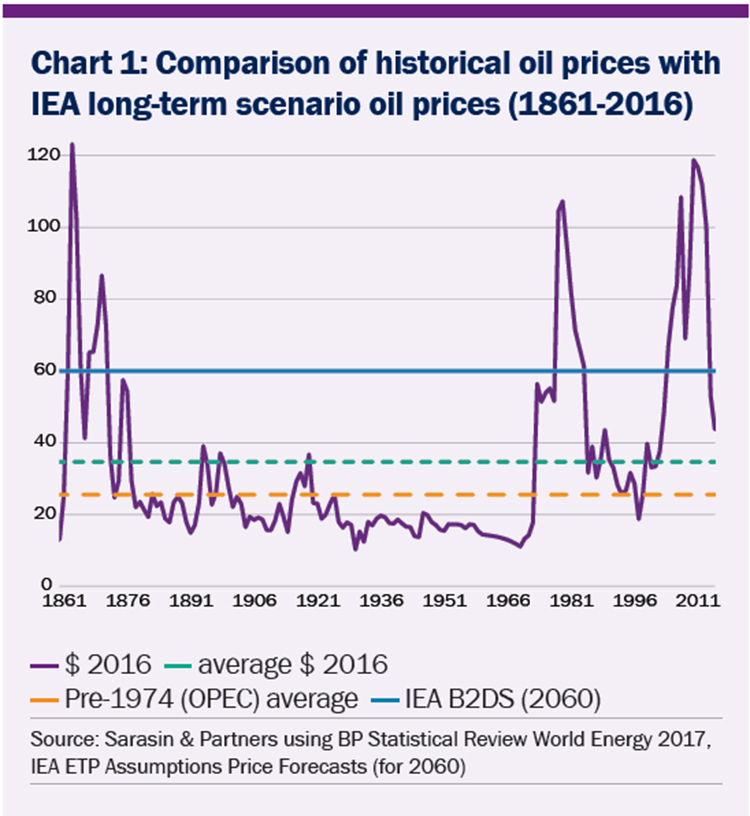

Historically, average oil prices from 1861 to 2016 (in 2016 prices) were $35 (see chart). If we cast our gaze ahead, the International Energy Agency sees a $60 price as likely when we take account of global decarbonisation to achieve the “well below 2oC goal” prescribed by the Paris Climate Accord. This requires the world achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2070, and some believe this should be far sooner. For its part, the UK government estimates a $55 long-term oil price, factoring in demand reductions in line with reaching the Paris goal. Others, like the think tank Oil Change International, believe there will need to be a faster reduction in demand, resulting in a price closer to the historical average of $35.

A price too good to be true

External benchmarks provide a sense check. But what is even more striking is that the oil companies themselves appear to agree that the $70 to $80 price assumptions used in their financial statements are too aggressive.

In contrast to the $70 to $80 long-term oil prices used in their accounts, the same companies are developing their operating strategies using an oil price assumption of $50 to $60. Royal Dutch Shell requires that proposed new investments cover internal rates of return at $40, and BP aims to ensure its operations are break-even at $35 to $40 by 2021.

The lower prices used for capital deployment are consistent with the companies’ recognition that decarbonisation poses a structural headwind. All, to varying degrees, highlight the strategic threat in their narrative disclosures to shareholders that over coming decades they will need to navigate an accelerating decline in fossil fuel demand. The Norwegian oil and gas major, Statoil, has even changed its name to Equinor to reflect its determination to stay relevant in a low carbon world.

Are oil companies still as profitable?

If $40 to $60 is appropriate for designing strategies or approving capital deployment in an uncertain and shifting energy market, why then are accounts – that are supposed to be prudent – using $70-$80 per barrel? Perhaps this is because at lower oil prices the businesses are no longer profitable.

In 2017, Total reported in a note to its accounts that a 10% reduction in its oil and gas price assumptions (so $72 instead of $80) would halve its reported profit.

This is not small beer. Would a $60 oil price assumption wipe out all its profit? What does this mean for dividends? Taking a macro perspective, what does it mean for financial stability where the exposure to fossil fuel based businesses extends through supply chains and even banks?

The importance of commodity price assumptions is routinely identified by external auditors as one of the most material areas of accounting risk in oil and gas companies’ reporting.

Oil pricing impacts the whole business

The reason long-term oil and gas prices are so impactful for reported profit and capital is because these prices govern estimated future cash flows associated with all the main assets on the balance sheet, such as property, plant and equipment, joint ventures, goodwill, and deferred tax assets. For the companies we reviewed, these items amount to 60 to 75% of total assets. For BP, this translates into roughly $153 billion of potentially affected assets; for Royal Dutch Shell $280 billion. Other assets may well be impacted too.

Further, liabilities may also be understated due to optimistic oil prices. Decommissioning and remediation obligations – roughly 25% of total liabilities for the companies reviewed – would rise if lower oil prices bring forward the decommissioning date. Pension obligations may also become more onerous if the underlying sponsor (the company) is viewed as riskier.

The price assumptions feed into reported profits through their impact on expenses like depreciation and impairments. If asset lives become shorter, depreciation expenses rise, bringing profits down. Similarly, write-downs cut profits and the reserves from which dividends are paid.

Recent accounting scandals mean action

On the back of repeated accounting scandals at large listed companies like the supermarket chain Tesco, the telecoms giant BT, and – most recently – the outsourcing company Carillion, complacency would be foolhardy. Action is needed at several levels.

First, directors of oil and gas companies need to satisfy themselves that the key accounting assumptions are both internally consistent and prudent in a world that is transitioning to zero net carbon emissions. They should disclose to shareholders the sensitivity of the business to lower oil prices.

Second, external auditors need to strengthen their stress tests, and provide additional disclosures to shareholders to justify their opinion that company accounts provide a true and fair view of the entities’ economic health, as well as a sound basis for dividend payments.

Third, regulators need to make sure directors and auditors act by clarifying their duties under accounting and capital maintenance laws. Accounting standard setters could also play a supportive role by promoting comparable and prudent reporting that takes account of decarbonisation aligned with the Paris Accord.

Finally, shareholders must demand greater transparency around accounting assumptions and prudence through dialogues with directors and auditors, and ultimately through their votes at annual general meetings. These accounting disclosures should form an integral part of disclosures under the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosures.

Shareholders must be aware of these assumptions

For US oil and gas companies, shareholders are starting from scratch. They generally lack any visibility of the long-term prices used to draw up financial statements. Investors are not able to compare results of different companies (are they comparing apples and oranges?). More importantly, they are in the dark over the capital strength and profitability of their companies. This needs to be urgently addressed.

A low carbon world means – ultimately – a low demand world for fossil fuels. While company narratives are changing in recognition of this fact, their numbers are not. In light of this, the oil price assumptions being used in company accounts do not look prudent; this puts shareholders and creditors at risk. Overstatement by fossil fuel companies also works against efforts to combat climate change as higher reported capital and profit cause more investment in fossil fuels (and bonuses will likely be paid for doing so). The longer the adjustment is delayed to clearer and more realistic accounting, the greater the risk of harmful disruption. Shareholders will not be the only casualties.