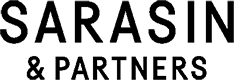

Perhaps the most significant change on earth over the last 50 years has been the increase in the human population, from 3.6 billion to 7.6 billion people today. This has required us to grow more than double the amount of food and created huge pressures to inhabit areas once the preserve of wild plants and animals. The impact has been massive biodiversity loss, that is to say ecosystem degradation and a collapse in the animal population.

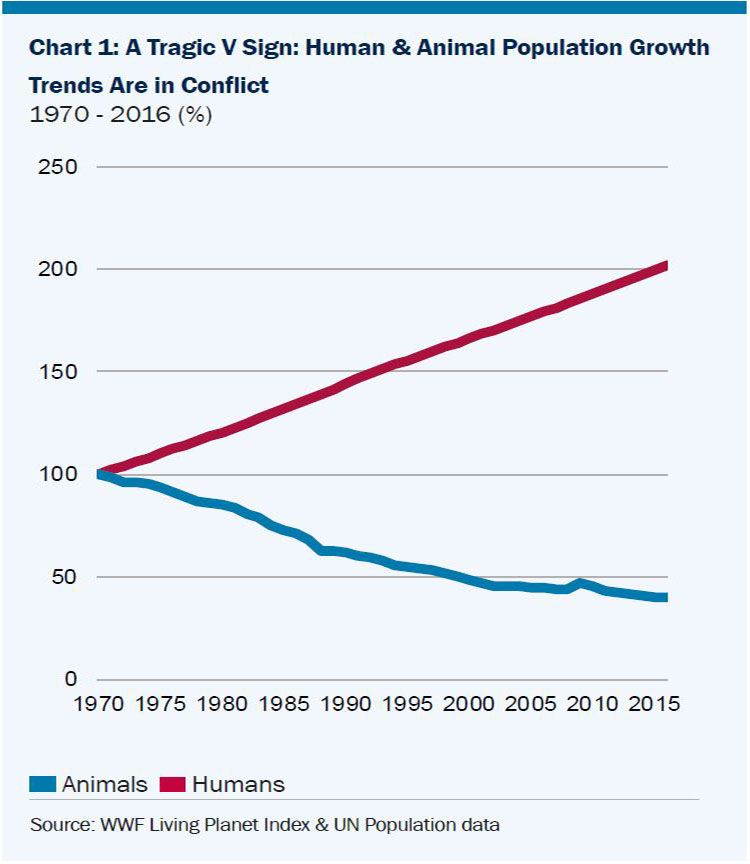

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF)’s Living Planet Index measures the abundance of 3,706 vertebrate species. Its 2016 audit shows that global populations of fish, birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles declined by 58% between 1970 and 2012 and the decline could reach 67% by 2020. This rate of species loss clearly upsets the balanced ecosystem that has evolved over millions of years and threatens earth’s life support system, particularly when considered alongside the degradation of ocean health, forests, fresh water sources and the atmosphere.

The value we gain from a properly functioning ecosystem is taken for granted and the threat is very hard to see. The WWF data is therefore a very important chink of light that allows us to measure the problem. When we do put a value on nature, it is seldom aligned with sustaining biodiversity. We assign a low value to mosquitoes, slugs or red-fanged funnel spiders (a highly endangered species), but a high value to cows, wheat or sugar cane. Clinically, we can view biodiversity loss as an economic problem containing elements of inefficient pricing and market failures, including insufficient incentives and resource misallocation. But it is a problem of such scale that it must combine educational, political, legal and economic responses.

The Farming Policy Imperative

First and foremost, biodiversity policy must target farming practices. The cultivation of land to grow food and more recently biofuels has pressured biodiversity more than urban development or industrialisation (although the trends are inter-linked). The State of the World’s Plants report, by experts at the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, names 390,000 plant species. But three alone (rice, corn (maize) and wheat) provide 60% of the world's food energy. The report identifies food production as the biggest extinction threat to plant species, due to the destruction of habitats from activities such as palm oil and soybean production and cattle ranching.

Much of our biodiversity lies on private land subject to unnatural economic pressures. In Europe and the US, most farmers earn less than a 2% return on their capital, hence unsurprisingly landowners are forced to seek to maximise returns on their capital. Protecting biodiversity is often in conflict with this goal, not only because there is a lack of financial reward for protecting biodiversity, but government subsidies often encourage agricultural intensity or create perverse incentives to destroy protected species so as not to compromise agricultural production.

Since the biblical story of Joseph in his multi-coloured coat advising Egypt’s Pharaoh on grain management to avoid famine, governments have intervened to manage food prices and agricultural production. Today, government policies encouraging the use of biofuels are having a particularly momentous impact. It is claimed these are ‘green fuels’ because biofuel crops absorb as much carbon dioxide (CO2) when growing as the biofuels emit when burnt. This is unsound: biofuels produce less CO2 overall than fossil fuels, but they are not carbon neutral. Fossil fuels are used in the fertilisers that help biofuel crops grow. And these crops impose massive pollution and opportunity costs in biodiversity terms given the land and other resources that they demand. For instance, last year, the US corn crop alone covered 88 million acres (an area one and a half times the size of the UK) and required an estimated 5.6 cubic miles of irrigation water and 6 million tons of nitrogen in fertilisers. Some 40% of the corn produced was used for bioethanol to be blended with gasoline.

In one study, Cornell University found that producing ethanol from corn requires more energy than the end-product itself is capable of generating. This raises even more questions about incentives to produce biofuel crops (such as corn, palm oil, rapeseed, sugar cane and soybeans). In a future world of electric cars, will taxpayers be happy continuing to pay large subsidies to produce a crop that has questionable purpose?

Where is government policy heading?

Within the confines of the capitalist system, several governments are now embarked upon more meaningful conservation work to analyse the impact of subsidies on agricultural practices and consumer behaviour. As the UK prepares to leave the EU, its government is seeking to address the shortcomings inherent in the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). The Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Michael Gove, wants to end the CAP’s "unjust" and "inefficient" subsidies that reward "resource-inefficient practices" and "incentivises an approach to environmental stewardship which is all about mathematically precise field margins and not truly ecologically healthy landscapes". His department is reconsidering subsidies, tariffs and trade relationships, and also examining the impact of climate change, information technology and bio-tech changes like gene editing.

There are three main directions of travel for government agricultural policy to enhance biodiversity. First, it can stick with current market mechanisms, whose impact is questionable. Secondly, it can seek to enforce protected areas to conserve natural resources like forests, peat and grasslands. A third option would involve governments generating stronger economic incentives to correct the market forces that undermine biodiversity. These might include outcome-based subsidies (for example, rewarding greater species density) or taxes on activities inflicting ecological damage. Many such ‘agri-environment schemes’ (AES) have been tried on a small scale in the EU and the US. But to make a significant impact on the biodiversity threat, a complete re-education and realignment scheme for land management is required.

At a multi-national level, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly has declared 2011-2020 as the ‘UN Decade on Biodiversity’. It is implementing a strategic biodiversity plan that incorporates five broad targets to address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss: promoting sustainable land use; safeguarding ecosystems, species and genetic diversity; promoting and enhancing the benefits to all from biodiversity and ecosystem services; and working on planning, knowledge management and capacity building. We will hear much more about this in the run-up to the next ‘Conference of the Parties’ meeting of multinational governments in 2020.

We all might have behaved very differently over the last 50 years if we had known in 1970 that our behaviour would wipe out two-thirds of the animal population by 2020. Extinction risk sounds melodramatic, but it will be brought increasingly into the public consciousness in coming years, with far-reaching consequences for government policy, corporate profits and consumer behaviour.