How television is evolving

Our world is being reshaped by the coronavirus pandemic, in ways both big and small. Governments and central banks are taking unprecedented steps to support their economies, countries have closed their borders, and as social distancing becomes widely practised, people are replacing physical interactions with online ones. Digitalisation is one of the five investment themes we seek exposure to in our portfolios, and the pandemic is further digitalising our world, with many of the digital trends that are already in motion accelerating. Digital companies are finding themselves playing an increasingly significant role in society, as people rely on online shopping, working, communication and entertainment. The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 has become a reference point, but self-isolation without the ability to access the world digitally is a sobering thought indeed.

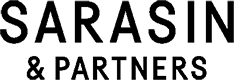

In a quarantined world, demand for online entertainment is soaring. Yet the world of television had already been undergoing a period of intense change. When John Logie Baird and Philo Farnsworth pioneered the television in the 1920s, they could have hardly imagined a world where the majority of people would consume television via online streaming services. But this is the state of play in 2020. Over the past decade, paid online video-on-demand (VOD) subscriptions from providers such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Apple TV+ and Disney+ have grown by 37% year-on-year. Estimates suggest that by the close of 2020 there could be over 800m paid subscriptions globally1. And whilst these subscriptions have been increasing, the number of paid television subscriptions has been falling at a significant rate. Recent data suggests that US cable subscriptions have been falling by mid-high single digits for the last 4 years (figure 1).

An old business model’s power wanes

Pay TV services have been a mainstay in homes across the developed world since HBO launched in the United States in 1972. Up until recent times, both providers of Pay TV and media networks benefitted from the success of the business model, fuelled by growth in both the number of households subscribing, and the amount that each household was willing to spend in order to watch television.

The original business model saw Pay TV providers such as AT&T, Charter and Comcast (now owners of Sky) charge consumers a monthly subscription fee for a bundle of channels. In turn, they pay an ‘affiliate fee’ to a media network, such as Disney, for the right to broadcast Disney’s own premium channels, such as ESPN and The Disney Channel. These media networks also benefit from revenues paid to them for advertisement slots during broadcasts, which drives competition for the best and most-watched content between networks.

Indeed the most-watched content can be so lucrative that competition for the right to broadcast the most-watched content has driven costs to astronomical levels. In times of increasing subscriber numbers and subscription fees, this would not be an issue for a media network such as Disney’s ESPN; they would simply pass on the cost of their content to the Pay TV provider, by demanding an increased affiliate fee from them to continue showing their channel. The provider would have no option but to pay up, or else risk losing subscribers. However, in the face of higher costs, consumers are beginning to cut the cord. Increasingly, they cancel their Pay TV subscriptions and sign up for online streaming services.

How can media networks remain relevant? The problem they face is a classic case of the innovator’s dilemma. The innovator’s dilemma is a concept first put forward by Harvard professor Clayton Christensen in 1997. Christensen suggested that even if incumbent companies carry out their business plans without error, they will still lose out to disruptive companies who embrace new technologies and gain market share. In this framework, traditional media networks are the incumbents, whilst online video streaming providers are gaining market share by embracing the new technologies. Incumbent media networks have a choice: choose to do nothing and harvest the remaining, diminishing returns of their businesses, or shift themselves back to the beginning of the life-cycle of technology in order to capture a part of the modern-day growth story that is online video-on-demand. However, doing this will result in short-term losses for the business. What makes this scenario incredibly interesting is that whilst the situation presents a dilemma to these companies, it will undoubtedly present some investment opportunities.

How can a traditional media network compete with netflix?

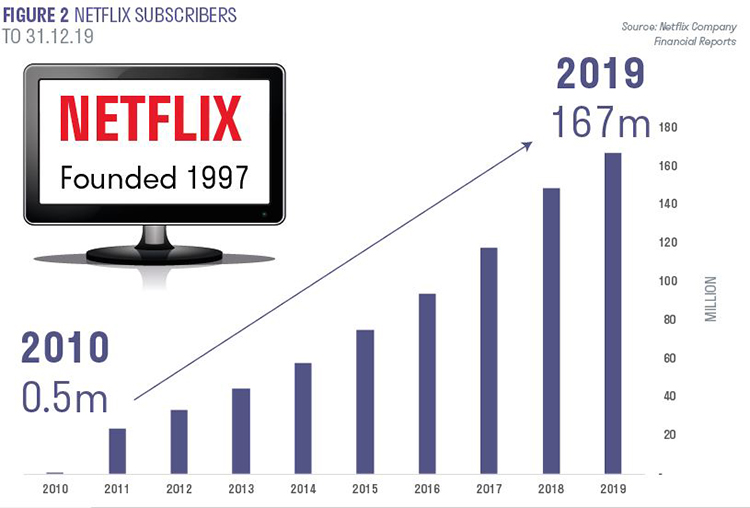

Netflix is widely regarded as the market leader within online video-on-demand. It began life in the late 1990s as a subscription-based DVD rental service, before expanding into online video-on-demand throughout the 2000s. In the last decade, as figure 2 shows, the number of subscribers has risen exponentially, from 509,000 in 2010 to over 167 million at the end of 2019. However, a number of new entrants, such as traditional media networks AT&T, Disney and Comcast, and technology companies Apple and Amazon, have entered the online video-on-demand market and are now attempting to gain market share.

With such a large number of new entrants into the arena, it seems unlikely that all can be successful. Firstly, consumer survey data suggests that most consumers are likely to only sign up to a maximum of three online video-on-demand services. This is the point at which the average consumer does not experience any financial saving from cancelling their pay-tv subscription and switching to online video-on-demand subscription. Secondly, because of increased competition for subscribers, the companies behind the video-on-demand streaming services are increasing spending on new, original content to levels that could prove to be unsustainable. Nonetheless, it is certain that there will be more of these streaming services before there are less.

How to succeed in the new world

To be successful, a streaming service will need a substantial portfolio of appealing, differentiated content. These can be companies with unique and popular intellectual property such as Walt Disney, who have an unparalleled library of content that has gained consumer affinity over generations. Access to strong distribution, or ownership of distribution, is also key to success as it ensures that subscribers are able to access the streaming service in an efficient manner. Netflix is one such company. Roku, which has popular distribution platforms that can host streaming services, is another.

How will television evolve in the future? It may be too early to speculate, but it is feasible to assume that upcoming film releases could be released straight onto video-on-demand services, given the closure of the cinemas. In the United Kingdom, broadband network providers are adding capacity to their networks and have reiterated that their networks will be able to cope with the additional demand. The times ahead may be testing, but there will be no shortage of video content to consume online.

1The Walt Disney Company 2019 Investor Day Presentation. Slide 10