It has over 5,000 listed companies with a market capitalisation of $11 trillion.

That’s just under its $12 trillion GDP. By comparison, US equity markets are valued at around US$30 trillion – or 1.4 times GDP.

The opportunities for our fund managers, and other leading global investors, ought to be plentiful.

But Chinese opportunity is leavened with limitations. Government constraints, high debt levels and other factors mean the best opportunities lie in a few portions of the economy – or in global companies doing business in China.

The first limitation is because the country has a dual track corporate sector: some companies are private while others are government run.

Private companies, often referred to as SMEs, or small and medium sized enterprises, have been the lifeblood of a more vibrant economy since former leader Deng Xiaoping signalled the start of ‘reform and opening up’ in 1978.

SMEs are reputed to represent 90% of total exports, 80% of urban employment, 70% of patenting activity, 60% of GDP and 50% of tax revenue. The sector in aggregate earns an 8.5% return on assets, and has spawned investment opportunities such as Alibaba and Tencent.

On the other hand, centrally-controlled state owned enterprises (SOEs) have played an important role in China’s recent development. Onshore listed SOEs account for 29% of all firms and 43% of market capitalisation.

But they typically earn a lowly 2% return on assets, are highly indebted, frequently loss making, low growth businesses, badly in need of reform. They have not been good investments.

State control doesn’t end there. Government policy has a significant impact on the fortune of companies – to an extent we’re not accustomed to in the West – and it currently favours SOEs.

It’s tempting to believe China’s rulers have the tools and ability to effectively manage their economy. But in truth, they’re making it up on the hoof: the system is complex, policy errors occur and frequent course correction needed.

The squeeze on private firms

We only need to look at what’s in front of us to see that in action.

China started reducing debt in 2018. But the banks, themselves predominantly state owned, continued to lend overwhelmingly to SOEs.

Private firms, with limited access to bank lending and corporate bond issuance – and reliant on shadow banking, stock pledging and intra-company loans – suffered a huge liquidity squeeze.

This led to a sharp slowdown in late 2018.

Course correction

Fearing the impact on employment, in November 2018 President Xi Jinping committed to support the development of private enterprises. This includes lower taxes and fees for private companies and at least a 30% increase in lending from the five large state-owned banks.

Early indications suggest this has improved conditions for SMEs.

It’s unclear if Xi has fundamentally changed his beliefs about state control or if he’s simply being pragmatic.

More clarity would help – firstly because if they prioritise investment in low return, unreformed SOEs it would reduce economic growth potential.

Secondly, an uncertain investment climate and a lack of business confidence constrains the returns available from higher quality private companies that might be of interest to our fund managers.

Investing in Chinese equities

Xi is determined to raise China’s profile around the world. The Made in China 2025 plan prioritises technology and it will need extensive private sector investment and a strong corporate sector.

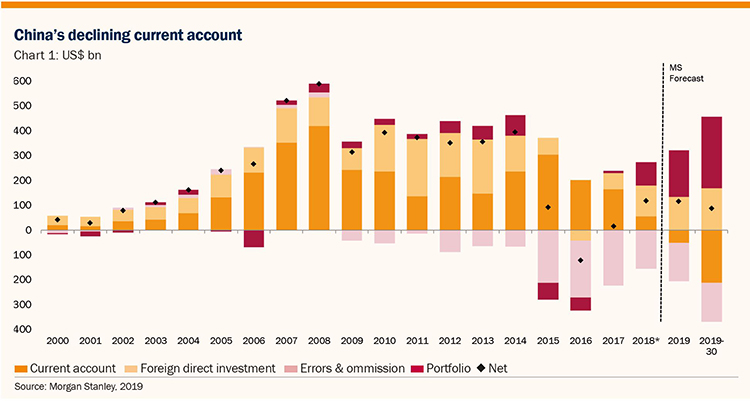

China also needs more international capital because it has less of its own.

Once around 10% of GDP, its current account position is being pushed down by a range of factors towards zero. This is why the country has taken steps to improve access to its domestic equity market.

While progress will probably be slow, over time the $11 trillion Chinese equity market will become increasingly accessible to our portfolios.

But that’s in the future. Today, opportunities are limited.

When China opened domestic equity markets in the 1990s, only SOEs could list and foreign investors faced tight restrictions. Around 2000, a wave of new private company listings was allowed and this redressed the balance. But there are constraints on daily fund flows and eligible stocks.

This has led to three types of Chinese shares: onshore Renminbi (known as China A shares), offshore Hong Kong dollars and international (mainly in US dollars).

Actions have consequences. For example, New York listed Alibaba is rumoured to be seeking a secondary listing in Hong Kong. That innovative Chinese technology champions were historically forced to raise capital outside of China remains a source of embarrassment for the ruling authorities.

Today, the most interesting potential investments are in entrepreneurial private companies. Given that we have a clearly defined investment process and philosophy, where, for example, we want a minimum cashflow return on investment of 8% and a market, means we’re looking at a list of just 90 companies.

Domestic opportunities

Our investment process emphasises thematic growth companies and integrates a deep understanding of environmental, societal and governance aspects in our analysis.

That’s not easy to implement in a market with no investor stewardship code.

Our rigorous analysis and screening makes us necessarily selective. So, at present, our global equity buy list has just four companies from the MSCI China and MSCI Hong Kong indices: Tencent, Alibaba, AIA and WH Group.

International opportunities

We’re looking more at global companies, listed outside of China and Hong Kong, providing attractive goods and services into China.

They have good standards of disclosure and accounting and are willing to engage with shareholders.

Until Chinese capital markets mature and governance standards improve, this is likely to be our preferred channel into Chinese growth.

China now represents more than 30% of the global market in luxury goods, cars, consumer appliances, mobile phones, and spirits. Branded consumer companies in luxury goods and staples have a high proportion of their potential sales in China and some durable competitive advantages. For example, European luxury brands, with hundreds of years of heritage, are impossible for the Chinese to replicate domestically.

Education, personal care, food away from home and travel are all areas of consumer spend supported by strong thematic drivers.

Healthcare is a large and growing market for innovative Western companies. Chinese healthcare is around 5% of GDP, substantially lagging the 8% spent in Europe or 16% in the US. As the population ages rapidly this will increase.

China needs to develop its domestic pharmaceuticals market, where research and development also lags developed markets (such as the 15% in the OECD), and in the meantime it will continue to rely on imported drugs.

Beyond the broad consumer opportunity, there are also select industrial companies that can benefit from China’s development.

The penetration of automation and robotics in China still lags that of Japan or South Korea, despite 10 years of rapid growth. In crucial niche markets, such as analogue semi-conductors, US companies such as Texas Instruments retain a leadership that will be difficult to displace.

Moreover, deepening Chinese financial markets provide an opportunity to financial services firms such as Allianz, UBS or Prudential that have recently been allowed greater access to the domestic market.

China’s a uniquely interesting and challenging market in which to do business and to invest. Our investment process is rigorous, selective and vigilant of the risks.

Some of these are political: aside from the China / US trade war, the former’s emphasis on ‘military-civil fusion’ raises national security issues for the latter.

But it’s undoubtedly an exciting source of good investment ideas – especially because of its growing marketplace for international companies.